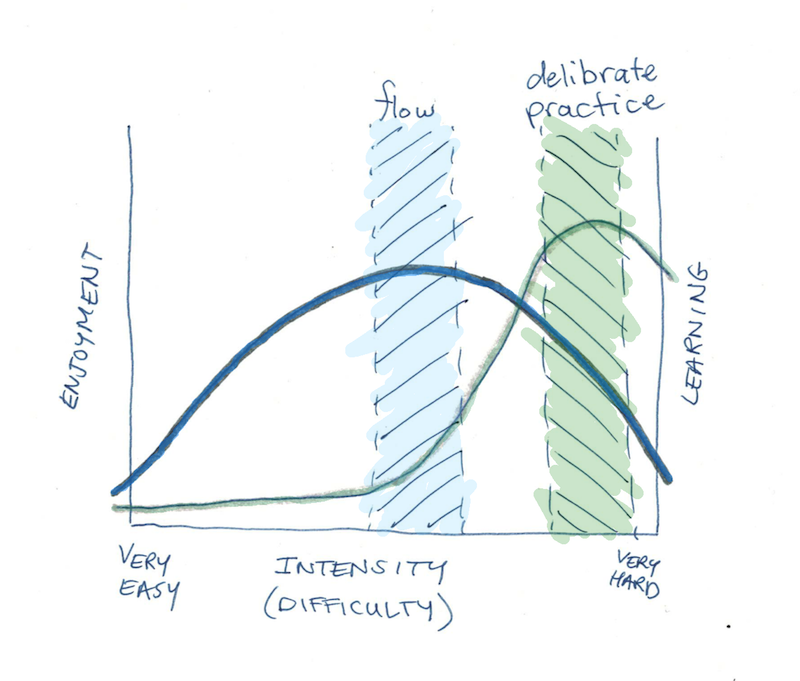

The concept of flow, first introduced by psychologist Mihály Csikszentmihályi, is the enjoyable feeling that happens when you are totally immersed in an activity. You stop feeling self conscious, with your attention being completely absorbed by the task at hand.

Chances are you’ve felt flow many times before. Maybe during a game, sports or even your work. Often your performance is best during a flow state—you may have felt your best games or work come from the flow of effortless focus. But what about learning?

Anders Ericsson, the psychologist behind deliberate practice, argues that flow doesn’t lead to mastery:

“[T]he characteristics of flow are inconsistent with the demands of deliberate practice for monitoring explicit goals and feedback and opportunities for error correction. Hence, skilled performers may enjoy and seek out flow experiences as part of their domain-related activities, but such experiences would not occur during deliberate practice.”

Ericsson believes deliberate practice—a specific type of practice characterized by immediate feedback, focused improvement and mental strain—is the activity that produces mastery. Yet, he also argues that this is “inconsistent” with flow.

Effective Learning is Effortful

This idea, that learning is most effective when it as done at a level of mental strain above what would typically constitute enjoyment, is a big part of the logic motivating ultralearning.

It’s no surprise that people tend not to like mental strain. Contrary to the assumption that elite performers and experts are intrinsically driven to improve, Ericsson finds evidence that, “deliberate practice is not inherently enjoyable, but individuals engage in it as an instrumental means to improve their performance to attain the highest levels.”

Comparing accomplished musicians with those of lesser achievement, Ericsson finds:

“[T]he best musicians spent very little time on playing music for fun and less time on leisure than other less accomplished expert musicians and nonmusicians of the same age.”

This drive to practice did not come from the best musicians simply enjoying deliberate practice more. Rather it came from their desire to get better.

With ultralearning, the idea is very similar: engage at a level of strain and mental difficulty that exceeds your comfort threshold. No, it’s not always the most fun, but that’s also why it works. Most people don’t see the same results from ultralearning in their self-motivated learning projects because, without strongly structured external motivation, most people don’t reach a high enough level of intensity.

Consider that most people, when looking for online classes, seek out good lectures and videos, rather than good problem sets and homework. Watching lectures is easy. It’s not deliberate practice. Actual mental strain working through the problems in question is hard, but it works.

Learning for Fun

This pursuit of uncomfortable intensity isn’t entirely without rewards. Long-distance runners also experience painful intensity in their sport, but this can come with a “runner’s high” that can be addictive. While I don’t know of any neurochemical basis for an “ultralearner’s high”, learning with such intensity often has a similar joy.

This doesn’t mean learning intensely is always a grim chore. Instead, I’m arguing that learning (like running) shouldn’t be expected to yield results at a level of intensity that feels like flow.

Setting ambitious learning goals and tight constraints, as I’ve tried to do in my own projects, is one way of regulating the environment to push the intensity higher than your comfort level. Another method, as Ericsson advises, is to get a coach to work with who can push you.

For some, the object of learning itself may be so compelling as to push the learner into a state of intensity, even if that spirit was never formalized as a goal. I think it’s likely that Albert Einstein’s quest to understand the universe or Bobby Fischer’s obsession to become the best chess player of all time, could have generated the required intensity.

However, I’m also agree with Ericsson that learning simply for fun, without any such constraints, is unlikely to lead to mastery.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.