What is self-discipline? I think everyone has at least a hazy picture of what it means to be self-disciplined. From the outside, self-discipline looks like suppressing impulses to do things you shouldn’t do. Self-discipline means not eating too much, not succumbing to the temptation to check your phone every two minutes, ignoring what you want to do and doing what you should.

Everyone has experienced being self-disciplined—that time when you valiantly resisted an impulse you thought you shouldn’t follow. But, more often than not, we have the opposite experience: failing to be self-disciplined, succumbing to temptations.

This outside-view and numerous experiences would make it seem likely that we should all be experts in self-discpline. If not in practice, then at least in theory. We should know why we persist when we do, why we give up and what’s going on inside our heads in both cases. After all, experiences of self-discipline—both in failure and in success—happen every day.

Yet, I think this familiarity doesn’t necessarily equate to understanding. I’ve written about self-discipline for years, but recently I’ve had some experience that make me rethink what it might be all about.

Is Self-Discipline a Resource?

The easiest metaphor, and the one I’ve operated on implicitly for most of my life is that self-discipline is a kind of resource. Use more self-discipline and it will get used up and you’ll feel tired.

Intuitively this seems to be the case. With few exceptions, most people can’t endure indefinitely in a situation that requires constant willpower. Eventually we give up, and when we do, it seems likely that there was some kind of fuel that was used up in the process.

Scientifically, this also seemed to be the case until recently. Roy Baumeister’s research into ego-depletion was seen as a pretty solid edifice to the idea that there is a bottleneck in the amount of willpower you can expend, and when it gets used up you succumb to whatever temptation you’re facing.

However, Baumeister’s work has also fallen victim to the replication crisis in psychology. Whether this is truly an invalidation of his theory, or the presence of statistical complications that go over my head, I think remains to be seen. For the moment at least, it appears that science doesn’t have a definitive answer to the question of what is self-discipline.

Although less scientific, the concept of energy management dovetails nicely with ego-depletion. The fundamental idea is that there are different stores of an abstract quantity of energy and that managing this resource, and not time management, is the key to productivity. This has also been a foundational idea in my own thinking on productivity and I’ve written in support of it quite often.

What if Self-Discipline Isn’t a Resource?

I just got back from an intensive 10-day silent meditation retreat. Some of the experiences bordered on insanity, and perhaps I’ll share more about them when I’ve had time to process them. But one of the aspects of my life it shed light on was this concept of self-discipline.

Going on a meditation retreat is like becoming a monk for ten days, except instead of even the duties one would have as a monk, there’s just more meditating. There’s no speaking, no phones, no computers, no reading, no writing, no exercising and no sex. Instead you wake up at 4am, meditate for ten hours per day, with short breaks to stretch your legs and eat two meals a day.

The outside-view of the meditation retreat is that all of the worldly pleasures you’re giving up will be the temptation. That you’ll be tempted to speak, want to eat in the evening, crave checking your phone or do something fun.

I can’t speak for others’ experience, but in my case, none of that was hard at all. The thing that’s hard about a meditation retreat is the meditating. Because even when you have nothing to do, there’s still a lot you can do: you can look around at things, walk around a little, scratch your face, change your position. When you meditate, even those minor pleasures are discouraged. Instead you’re to sit as still as possible and focus on some object of meditation, say your breath or sensations in your body.

Needless to say, meditating requires a lot of self-discipline. But is it the kind of self-discipline that gets consumed as a resource?

At first, that answer seemed obvious to me: the longer a meditation session went on, the more willpower I’d need to resist the urge to quit and go do something else. My back and legs would hurt, so I’d want to change my posture. I’d want to daydream about something else, engage in a little mental theatre imagining this scenario or that one. Yet—according to the technique—whenever this happens you’re to remind yourself you’re here to work and shift your focus back onto something happening right now.

As the days wore on, however, I started to notice something about my own self-discipline that seemed to contradict the resource metaphor. Sitting still and doing meditation was hard, but it was hard to the degree to which I was somewhere else. If my attention was fully focused on what I was doing, and not on, say, thinking to myself about how long this will last and when I’ll be free, the act got a lot easier. The longer attention was paid to the meditation without these interruptions, the easier it got.

This suggests a very different model of willpower, one based on attention and mental habit patterns, instead of a consumable resource.

A Closer Look at Self-Discipline

The idea is still very speculative, but here it is: at any moment, there are mental habit patterns that are compelling you to engage in some kind of action. Move. Change your posture. Think out a plan to solve this problem.

In addition to these mental habit patterns, there’s a broader quality of attention. What is being paid attention to in this particular moment. What is filling the field of your consciousness, at varying degrees of precision and intensity.

Self-discipline occurs when there is a mental habit pattern encouraging some further action and the attentional response is to not engage in that habit pattern. Not to resist it or try to push it out of your thoughts, but just to ignore it.

One metaphor that comes to mind is it is as if your mind is full of tons of whiny children who all want you to do something for them. At any particular moment, you can engage your attention onto one of the children—either by trying to fulfill its wishes, trying to argue with it or telling it to shut up. Or you can just see it and not react.

When you ignore it, the impulse will still be there, but it will eventually diminish in intensity, over both the short and long-term. Over the short-term, it will eventually quieten down because no thought, sensation or feeling can be permanent. They’re all unstable and eventually decay to normal neuronal background levels. Over the long-term, it will become less noisy in the future because that impulse, through being frustrated, is conditioned to be quieter next time.

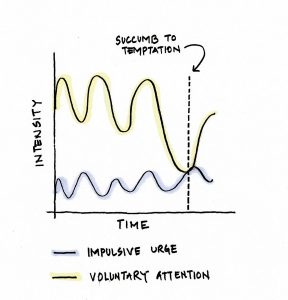

If this model is true, then self-discipline isn’t a resource at all. The problem is simply that voluntary attentional control is itself a somewhat random process that has ups and downs, starts and stops.

These ups and downs, or to use the term from Buddhism, arising and passing away, of both the impulses and one’s voluntary control over focus will occasionally create gaps, particularly in the short-term, where one succumbs to temptation. That’s because one’s impulse exceeds the attentional resources to not pay attention to it in that moment, and you succumb. However, no resource was consumed either before or after, simply an inevitable result from somewhat noisy processes competing for control over your body.

Side note: I’m creating a dichotomy between volitional control over attention and the impulses that impinge on it. This is probably not accurate. It’s probably better to say that the impulses of discipline are themselves one of the voices, but it’s that this is the voice you’re trying to amplify with attention while the others are being ignored. My explanation is probably a little less accurate, but I think it’s a bit easier to wrap your head around than the deeper idea that there’s no one thing really in control when we think of voluntary control.

Why Does It Feel Like Self-Discipline is a Resource?

This then raises an interesting question, why does it *feel* as if there’s a resource being used up, if the reality is just competing habit patterns in the mind and “voluntary” control over attention, why does it feel like we can run out of willpower. If I’m able to resist an urge for five minutes, why can I not do it indefinitely?

I think there’s three reasons for the seeming presence of an underlying resource. The first is environmental feedback. The second is in thinking of averages instead of individual events. The third is that knowledge of time is itself a feedback signal that influences our habits.

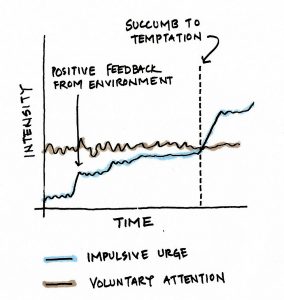

Environmental feedback can happen when, as one persists, the urge gets stronger and stronger because there is continued reinforcement in the form of bodily sensations that make it feel stronger. Hunger works like this. When you’re a little hungry you can easily resist paying attention to it. When you’re starving it’s the only thing you can think about.

In this model, some activities of self-discipline will create an increasing intensity until they are satiated. These intensities cannot reach infinity, so there’s always the possibility of someone resisting even the most intense urges when the voluntary control over attention is even stronger, but these are rare because it is very unusual to develop that kind of self-discipline (and probably harmful, in most cases—such as diseases like anorexia or pain-seeking behavior).

While meditating for instance, as you sit for longer, your body itself becomes increasingly uncomfortable. This means that it can be very easy to sit for 20 minutes, but very hard to sit for 2 hours, if your volitional control habits aren’t very strong. It’s simply much more likely after the 2-hour mark that the habit pattern to quit will overwhelm you.

This idea may seem to be bringing back the idea of a resource in a covert form, so it’s important to understand the distinction: nothing is getting used up. The only thing modulating behavior is the relative strength of different mental habits, and feedback from either the outside world or internal sensations, can trigger those habits with different intensities.

The second reason that willpower “feels” like a resource is that, if we consider it a stochastic process, there will always be an expected value. A Poisson process is a statistical model that envisions this nicely. In such a process, events always have some small probability of occuring in every moment. This creates an average time between events, but it doesn’t create a “building up” of energy that needs to release itself if an event doesn’t happen soon.

The third reason for willpower seeming like a resource is that one of the regulators of habits is itself a kind of knowledge of time. One powerful mental habit is that if you’re in some kind of discomfort, either physical or psychological, and you believe that this situation will persist for a long time, the urge to take action to change it becomes much stronger.

This tendency of the mind became very clear while meditating. In normal life, this mental habit can receive reinforcement from a clock or some internal pacing rhythm, which tells you roughly how long you have left. If it is a short time, this mental habit doesn’t react as strongly. If it’s a long time you need to persist, it can be a stronger urge than almost any other.

While meditating, however, one doesn’t have external time cues. Therefore this mental habit frequently gets frustrated because the amount of time left may be a few minutes or it may be over an hour, and you have no idea. Once again, by ignoring this urge to ask how much longer the experience will be, this time-habit diminishes in intensity.

What are the Implications of an Attention-Habit Versus a Resource Model of Self-Discipline?

All of this may sound a little too technical. Most people probably don’t even think of self-discipline clearly enough to see it as a resource, nevermind asking whether that is a simplification. Why bother thinking about this?

I feel like this idea, if it turns out to be correct and properly applied, opens up many new ways of thinking about self-improvement. So many of the things we want to achieve in life are based in requiring some kind of self-discipline. So many of the negative things we experience that we’d like to be free of are also mental habits of this sort.

I don’t have an exact picture of how to use this idea yet, but here are a few specultative suggestions for where it might be useful:

Building a “now” habit. The mental habit of taking mildly unpleasant conditions and making them seem excruciatingly unbearable if they are imagined to persist for a long period of time is quite a strong one. Does this mean it might make more sense to work in a room without clocks? So the feedback signal from this mental habit becomes less precise and therefore more unstable over time? In practice it could be replaced with a bell or timer indicating the time allotted for the task was finished and one could make an adjustment.

Ignore, don’t engage. Habits get stronger with use. At the behavioral level this is clear, but I believe it is also true at the mental level. To “use” a mental habit is to engage in it in any way. Trying to fulfill it, suppress it, even feeling guilty about having it are all forms of engagement. Just let it be, and don’t do anything. The Buddhist wisdom to simply accept a reality takes on a subtle meaning here of not engaging leading to mental freedom seems to be putting this idea into practice.

Far more self-discipline and control is possible than we realize. The idea that we have to succumb to certain temptations, that we couldn’t possibly put in *that* much effort or that life would be unbearable if it weren’t like X, Y or Z, may be false at a fundamental level. By slowly building habits of attention and letting ones you don’t want extinguish, much of the internal conflict you feel over what you should be doing and what you actually do might go away.

Applying this Idea in Recursive Stages

Part of what always bugged me about Eastern philosophies was that they told you to “accept” reality as what it was, but isn’t my own non-acceptance part of reality and therefore what I should accept? This seemed like a straightforward contradiction and I didn’t know my way out of it.

Now I see that the answer is that there are different levels of mental patterns and sometimes to counteract a particularly strong one you need a lot of attention onto an alternate pattern. However, this alternate pattern eventually creates its own weaknesses and so to go further, you have to give this up as well. This means that the idea of accepting non-acceptance has to proceed recursively, first working on the bigger picture and then onto subtler and subtler realities. If you just dismiss the whole notion because you know it eventually self-contradicts, you’re missing the progressive aspect.

What does this mean for self-discipline?

Well I can imagine starting out where one feels that they have no self-discipline at all. Here, this person needs to have fairly crude mental habits to rectify the worst of their impulse control. In this area, setting minimal habits to put even a tiny amount of effort into the task might be necessary.

Later, once some mental control structures have been built that avoid being completely at the whim of negative impulses, one might try setting up systems: things like GTD, fixed-schedule productivity, weekly/daily goals and other systems that work over a longer time-scale. These can placate somewhat that strong tendency of the mind to look for escape when the current unpleasantness will last for too long. By forming a structured system with a predefined escape time, you can build a habit of working hard inside that structure.

However, further levels of self-discipline might transcend this system itself. By reducing the impulse to do other things to a low enough level, one might be able to “work” on whatever you need to do nearly continuously as if it were a fun activity.

This isn’t to say that one *should* work continuously, obviously there is more to life than work. Rather its to say that the unpleasantness of work, the desire to have leisure time when you’re supposed to be working, would go away.

These successive layers of self-discipline, resulting in an extreme of an effortless kind of action, would require a lot of patience to slowly develop. Because going deeper into the structure involves working against the structure previously established, there’s always a risk of not realizing impulsive habits have been building up and losing the entire structure and needing to partially start over. However, that may be a worthwhile price to pay in the long-run.

As I said previously, there’s a lot to explore here and I’m not even certain that this is true. However, it lines up more closely with neurobiology than a resource-based theory of self-discipline, so I’m willing to accept it tentatively. Whether one can reach this theoretical end-goal of endless, effortless action, is still an open question, but the possibility is very interesting nonetheless.

Side Note: Robert Wright’s book, Why Buddhism is True, discusses many similar ideas, so if you think this discussion is interesting and want to hear from a better meditator and scientist than I am, you may want to check it out.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.