The classic view of self-improvement is that most people suffer from a motivational deficit. If they could just get that right bit of inspiration, they would summon up the courage to finally take action, start that business, get into a good relationship, run a marathon and give up junk food.

I happen to think that the opposite is probably true in quite a few cases: people struggle not from having too little motivation, but from having too much.

In doing research for my course on learning, for instance, I had initially expected (according to the classic view) that most people’s struggle with learning would be getting the motivation to learn something. Learning is hard, playing with your phone or watching television is not, therefore, I expected getting that motivation to learn to be high enough to surmount those distractions would be the most common problem.

In fact, I found the opposite was actually more common: people who had too much motivation—leading them to want to do too many things and finding it impossible to stick with a project until its execution.

Overly-Motivated Ideation, Under-Motivated Execution

An extremely common type of person I’ve encountered has two qualities which prevent her from making the accomplishments she would like:

- An overactive motivation to dream up ideas, scenarios and goals.

- A normal, or underactive, motivation to do the things implied by the ideas.

For this kind of person, giving them a motivational speech, inspirational book or pep-talk is probably going to have a negative effect. Why? Because it exacerbates her pre-existing tendency to go overboard on thinking up ideas of stuff to do.

Motivation, when applied, usually works best as a remedy to routine. If someone is stuck in a particularly ineffective pattern of behavior, then extra motivation might trigger a new push to improve.

Motivation, therefore, works best when there is a deficit of compelling ideas, not a surplus.

How to Tell if You’re Over-Motivated

I, myself, tend to be the kind of person with this personality, so I feel I can recognize it more easily in other people. I tend to get sucked up in some fantasy of a new project, travel destination or self-improvement kick. Those ideas are great, but earlier in my life they’d often lead me to disaster as I’d hop between projects without any commitment. It took me awhile to build the structures that could mitigate those potentially self-destructive aspects of my personality.

Reading this, you might realize that you too, suffer from over-motivation.

To get a sense of whether your motivation might be running too hot or too cold, consider the outcome of the last several failed goals in your life. These would be goals that you, at least at one point, had considered very important, yet they stopped progress or failed for some avoidable reason such as a lack of effort.

In each, ask yourself whether you stopped putting in effort because you simply lost interest, or because you started working on a different goal that started to take precedence.

Losing interest, and just having the time/effort invested get dispersed back to the low-level background noise of your habit patterns, is a sign of low motivation. For whatever reason, motivation wasn’t sustained on the project and it didn’t reach the finishing line.

On the other hand, having a new goal “push down” on an old project, so that the old project gets demoted in terms of priority while the newer project occupies your attention, is likely a case of over-motivation. Your failure to suppress the new idea led to your downfall.

In one-off cases, this tendency to replace an old goal with one that feels more important, may actually be wise. After all, your sense of priorities about things should guide how you allocate your limited effort and time. However, if it becomes a pattern of constantly cycling new self-improvement efforts which lead nowhere because they get replaced too quickly, this pattern can be self-destructive.

Motivation Curves

I’ve been painting a picture of motivation as if it were a unified psychological state, but that’s probably not true. The reality is probably closer to the idea that your mind is constantly full of competing motivations.

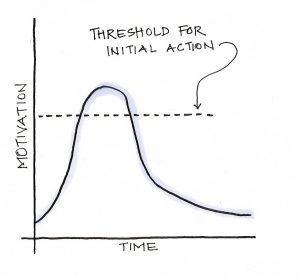

The typical curve for motivation may work something like this:

A particular motivation builds in intensity, until that triggers a threshold for taking initial action. The motivation continues as the work continues, but as with all affective states, it eventually returns back to more normal levels.

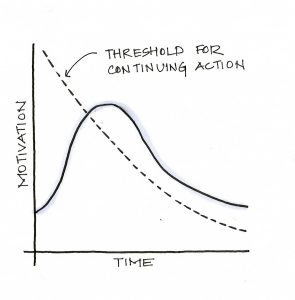

If you’re lucky, you’ve designed your project and goal in such a way so that the motivational threshold to continue working on it, is now below this new background motivational state. If it’s not—then you’re likely to give up working on it due to low motivation.

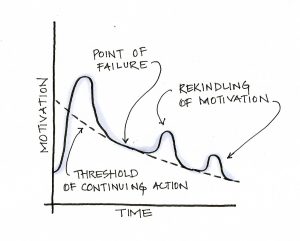

You may be able to sporadically bump up your motivation. For particularly long goals, this is almost a necessity. However, it’s still a less important factor than reducing the motivational threshold to continue working on it because the former is inconsistent.

I’ve written a lot about habits, goal-setting and project design. These ideas are, largely, to take advantage of the fact that you have a surplus of motivation in the beginning of a project, and use that extra drive to strategically design systems so that the long-run of your project has the necessary actions well below the motivational threshhold to continue them.

Side note: I realized a bit late my above graphs with a horizontal dotted line for “threshold for initial action” and a downward curving “threshold for continuing action” may be a bit confusing. It’s my take that these are different things. The initial action has a much higher motivational threshold because the action is new and nothing is a habit yet. Continuing action, in contrast, should get easier and easier (thus slope downwards) as more action automates at least some of the behaviors involved in pursuing the goal.

How Being Over-Motivated Complicates Things

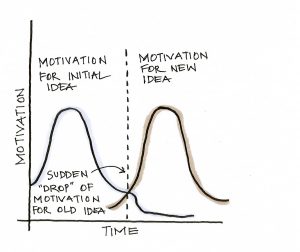

This above picture was for the motivation for a single goal or project. Things change, however, when you introduce the possibility of being motivated by different goals or projects. When this happens, there’s now an additional complication: your goal might get frustrated not because it was too onerous to sustain, but because a new interest robbed it of momentum.

For this kind of person, the curves are the same, but now you have competing motivations which draw from the same limited set of time, effort and enthusiasm:

Often this can result in an endless cycle of new ideas trumping old ones, as you forever chase the motivation high of the idea, and neglect the relatively emotionally neutral phase of simply doing the work.

To be accomplished, therefore, requires throwing cold water on yourself to cool down these motivations, rather than trying to turn on the fire.

How to Deal With Being Overly Motivated

The single best strategy that has helped me deal with this tendency within myself is to use the single-project approach. Only have one major ongoing project which is the top priority. Everything else is secondary and nothing else can replace it until that project is completed.

In practice, this heuristic is more complicated than that simple rule. You might have different single projects for well-defined areas of life that don’t usually compete with each other for time, such as a work goal, plus a different goal you pursue after work. The line between what qualifies as a project, and thus is subject to this rule, and what qualifies as a habit, and thus is one of many, many things you expect yourself to do typically in the day or week, may be blurry.

However, even amidst these complicating details, I think the single-project philosophy is usually a good starting point. Plan as if you’re only going to have one dominant project, and use this as your rule for clamping down on the tendency to get carried away with motivation for new ideas while you’re still working on the old one.

Another strategy I’ve found helpful for dealing with overactive motivation is to plan projects without starting them. The idea here is that, in a whirl of ideas about some new thing you could do, you don’t want to lose it. But, instead of making concrete reallocations of your time and energy, thus messing up your existing project, it probably makes more sense to simply plan out how you would execute it, after your current project is complete. Write things down, make schedules, figure out what would be involved, and this small dose of reality will usually satisfy the urge enough to prevent you from getting lost.

A final strategy, which is too seldom applied but could be of great help, is to set less ambitious, shorter-term projects. If you know that you tend to have large spikes of interest in new projects, then try to pick projects you can work on for a month, instead of ones which will require years to complete.

Small projects are less ambitious, yes. But many types of pursuits can benefit from a month or two of sustained interest. Others will require more time, but perhaps not continuously. You may, for instance, work hard on an exercise goal for one month, then switch to simply maintaining your habits while you try something else. Later, when that fades, you can switch back to the original fitness goal and push for a new level.

The key difference between the small project approach and what overly motivated people do by default, is that you are intending this to happen, so therefore you plan around it. When you simply let projects succeed and fail on the basis of a temporary emotion, many projects may not have reached a sufficiently stable level to be maintained as a habit in the interim. If, however, you know that your exercise project is just one month long, that causes you to rethink how you’ll design it so that after that month it might be sustainable as a background activity.

Ultimately, the curse of being too motivated is also a blessing. It means you have a drive to accomplish things, and the possibility of fulfilling it. However, it requires a counter-intuitive kind of control because it involves actively resisting some of the impulses you might have to make your life better. If you can pull it off, though, the long-term picture is usually much brighter than one in which you’re constantly chasing the high feeling of a new idea, rather than the everyday reality of doing the work.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.