Why are we suddenly getting much better at Tetris?

Author and vlogger, John Green, raises this very interesting question in a recent video. Tetris was released for the Nintendo in 1984. At that time, far more people were playing Tetris than there are today.

And yet, performance on Tetris is better now, than it was then. A lot better.

Which brings up an interesting point: why would far fewer players, playing a game which is less objectively popular, nonetheless be much better at the game now, then in its heyday?

The answer actually has a lot to teach us about how people learn and what are the key ingredients needed for getting really good at something.

The Four-Minute Barrier

Years before the Tetris renaissance there was another feat of human achievement. Roger Bannister ran a mile in under four minutes.

Before this moment, many had considered such an athletic feat impossible. Yet, being an elite athlete with intense preparation, Bannister eventually ran a mile in under four minutes.

Today, however, running a mile in under four minutes is easy enough that even some high-school students can do it.

Why did something once deemed impossible suddenly become routine? The human body didn’t change. Miles didn’t get any shorter. Yet our performance exploded.

Record-Breaking Environments

I believe the key to understanding both the explosion in Tetris performance and the numerous post-Bannister four-minute runs, is that while individual human beings are the ones breaking records, the overall performance often depends on the structure of the environment and the communities in which the results occur.

In the case of Tetris, easy recording, uploading and sharing of gameplay videos was a pivotal innovation to create the performance improvements, despite a declining player base.

Being able to watch top players, live, gives enormous insight into how they practice. You can see which strategies are used. You can learn tricks, such as the placement of holes, depending on the game speed, and avoid common pitfalls that would have stymied excellent players in the early days of the game.

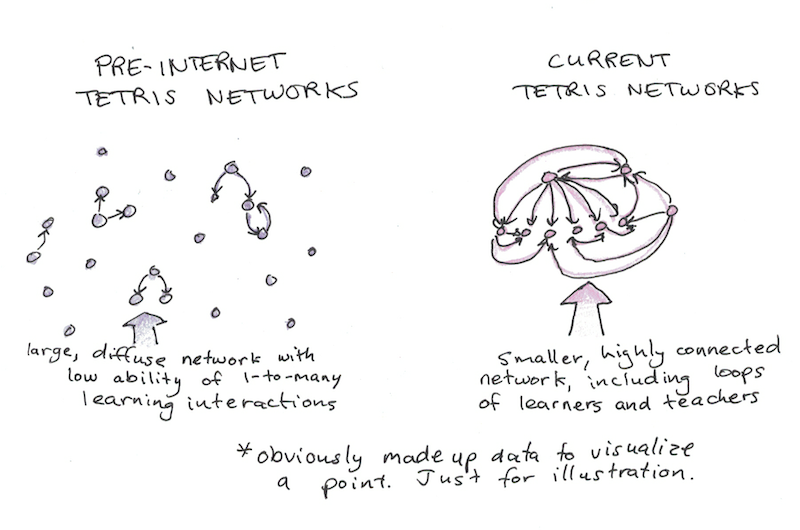

Plentiful live recordings, plus online communities for discussing those recordings, allowed a much smaller group of people to collaborate on improving performance much more than a much more diffuse, less well-connected player base of casual fans.

How the Environment Determines Growth

Take two genetically identical seeds, raise one in soil, with plenty of water an sunlight, and it will grow into a large plant. Take another and put it in a dark closet and it will die. Environments determine growth in many biological systems, so it wouldn’t be surprising if they had enormous influence over human-scale ones.

In our Tetris example, different social structures had different impacts on the growth in performance. Add the ability to see exactly how the best people are doing things, and a novice player can quickly get to the cutting edge. Have a large, diffuse player base and there is no accumulation of innovations. Each player must figure out what works best, on their own, through trial-and-error.

I suspect there are quite a few factors which determine this growth in performance, but I’d like to sketch out a few of the main possibilities here:

1. Being able to witness performance in others.

Recordings and streaming have made a big difference because they allowed players to learn via example. Prior to this, players could only learn by watching their best local player, or reading snippets of text descriptions from strategy guides which were often out of date.

Witnessing performance may matter a lot more than being able to understand performance. Studies show that groups which can copy can show rapid performance improvements, even when the individuals’ understanding of the principles behind their success are essentially zero.

I believe this is a highly-underused aspect of learning which we should foster more. Why are there plentiful recordings of video games, but far fewer recordings of high-level entrepreneurs going about their work? Engineers solving problems? Scientists doing experiments?

You may argue that privacy, selfishness or trade secrets prevent these, but I see these as being mostly technical obstacles. Open source software has succeeded on the same sorts of principles, despite being in competitive industries where both privacy and trade secrets are concerns.

2. Knowing that a goal is achievable.

The post-Bannister prevalence of four-minute miles is not a case of technical innovation resulting in an explosion of performance, but of breaking a barrier indicating that future performance improvements are possible.

Often, even if you can’t know exactly how someone achieved something, the mere fact that the achievement exists can help you in planning for it. The constraints around the accomplishment limit the scope of what strategies could have been used, and they also give you a target which you can strive towards.

In this sense, I see the posting of measureable progress made by Tetris players (and other competitive video gaming) as a component of what contributes to their success, beyond merely watching live replays. Knowing that someone has reached certain times spurs investment and innovation.

3. Having the right incentives to improve.

Patrick Collison and Michael Nielson report that our progress in science has declined. We used to make much more progress, with far fewer researchers, than we do today. A good question is why.

While speculation as to the causes of the decline in academic productivity is everywhere, one that strikes me as a particularly apt one is by former MIT AI researcher David Chapman.

Chapman argues that poor incentives, which encourage making token progress on unimportant matters in order to increase paper publishing count degrade scientific progress. Physicist Sabine Hossenfelder echos this sentiment arguing that modern physics has gotten derailed spawning endless esoteric models rather than focusing on hard, mathematically well-formulated problems.

Tetris players improve, not only because of their community and known achievements, but because the community is organized around accomplishing well-understood goals. Science, politics, and often business, can fail when the incentives that encourage participation (papers published, elections won, money earned) don’t reflect the true goals of those institutions (progress in knowledge, improved policies or value to customers and stakeholders).

How Can We Learn Better, By Adjusting the Groups We Belong To?

In some sense, these problems exceed the capacity of any one individual to solve them. Even the most inspired Tetris player in 1985, couldn’t have single-handedly changed the landscape of Tetris improvement. Pre-Bannister runners, couldn’t have had the benefit of knowing the 4-minute mile could be run.

However, there are two main ways I see this idea improving our thoughts on knowledge and growth:

1. Better designing of the communities and institutions around performance.

Thanks to the internet, brand-new communities, with new rules and incentives for behavior are being generated every day in the form of new social networks. The difference between Twitter and Instagram isn’t simply that the people are different, but that the mechanisms of how the community functions have been shaped by design decisions.

What’s stopping us from creating live-stream sharing where we practice skills which are actually useful? What’s to stop creating practice environments centered around skills with clear metrics for improvement? These things could exist, they would just take a few people with the initiative to design them, or integrate them into platforms which already exist.

2. Joining communities with the right characteristics.

If you want to learn a language, the best way is through immersion. This is because having an environment that necessitates non-stop practice makes learning so much easier than one where practice is always a deliberate effort.

Similarly, if you want to learn an important career skill, whether it’s design, programming, accounting, entrepreneurship or public speaking, the choice of where you choose to learn and practice may have more consequence than the methods or materials you end up using.

Look for groups where you can witness expert performance and emulate it. Join communities where you can see what goals are achievable. Go to environments where the incentives align with improving the skill you want.

Ultimately, whether it’s building a business, discovering new science or just getting really good at Tetris, the environment matters.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.