I’ve written a lot of stuff here in the past ten years. 1254 articles. Four books (and another on the way). Five courses. Hundreds of videos. Additionally, I’ve written at least another 100-200 articles for other publications over the years.

Being prolific has two main benefits:

- You get more chances for home runs. Not everything you do will be a brilliant success, but if you take more swings at bat, you’ll be more likely to produce a hit.

- Your quality goes up the more you practice. The more you make, the better you get at making things. There are exceptions to this generalization, but more does lead to better in most cases.

Talking with fledgling writers, the biggest struggle I see is how to produce enough content. How do you get to your first hundred posts? The same holds if you’re a musician, artist, photographer, speaker, designer or programmer. How do you make enough stuff to hit home runs and get good at your craft?

In this essay, I’d like to talk about my strategies for becoming prolific.

An Economic Analysis of Making Stuff

A valuable mental tool from economics is the difference between fixed and variable costs.

A fixed cost is something you must pay once, for everything you make. This is the factory you need to build to start making widgets.

A variable cost is something you must pay every time you make something. This is the raw materials you need to build each widget.

Being prolific, without having garbage quality, is a lot about recognizing the role these two costs pay in how you make things. This applies even when the stuff you make is purely intellectual, and the only cost is your time.

The $10,000 Invoice

There’s an old joke about a factory owner who has a machine break down. The hold up is going to cost him millions as nothing can get done before it is repaired. Unfortunately, nobody under his employ knows how to fix it.

?He calls around and finally gets a guy who has years of experience fixing things to come down and take a look. He tells him he’ll pay him whatever it costs to fix it.

The guy looks around for a few minutes, takes out a screwdriver, replaces a small screw in the assembly and, voila, the whole operation starts moving again. He hands the owner of the factory an invoice for $10,000.

A little upset at the exorbitant fee, he asks the man for an itemized invoice. He gets it sent again with:

- Replacing the screw …. $1

- Knowing which screw to replace …. $9999

The story is exaggerated, but it reveals an important lesson if you want to produce more work without sacrificing quality. Knowledge is a fixed cost. If you want to increase your output, without increasing costs, work on investing in the fixed-costs to making stuff.

What are the Fixed Costs to Making Stuff?

Your fixed costs in making things are the knowledge and skills you can bring into your work with little added effort.

1. Create a “Vocabulary” for Your Work

I try to spend a lot of my time learning. Books, articles, and even Twitter discussions, all give a larger base of things I can reference when I want to express myself. This makes writing a lot easier because a lot of my research is already finished before I even pick a topic.

You may not be a writer, but the same applies to you. As a designer, your vocabulary of designs, styles, methods and visual inspiration becomes a resource you can draw on to produce beautiful things. As a musician, your vocabulary of hooks, melodies and instruments all serve as fodder for new tunes. As a programmer, your depth of knowledge of the languages you work in and libraries that surround them give you more ways to solve problems quickly.

2. Master the Atomic Skills of Producing Stuff

The second aspect that aids in being prolific is having mastered the component skills, so that it doesn’t take so long to do all the steps.

When I started writing, it was hard to write good headlines, decide when to start paragraphs and end them, edit my documents and revise my thoughts. Now, most of this happens automatically because I’ve drilled it so many times I don’t even think about it. I can now look at my writing and get a feel for what needs to change, without too much analysis.

This isn’t to say I’m done learning. Far from it! There’s lots of things I need to improve. But when those improvements start, and I need to learn new skills, it’s often slow and painstaking to produce things.

Recently, I wrote my first book with a publisher. The workflow (and goals) I had for the book meant it was far, far slower to write than my normal articles. But, having learned some new atomic skills, my hope is the next book will be much smoother.

3. Make Failure Cost Less

Beyond investing more in skills and knowledge, the biggest barrier to being prolific is your own psychology.

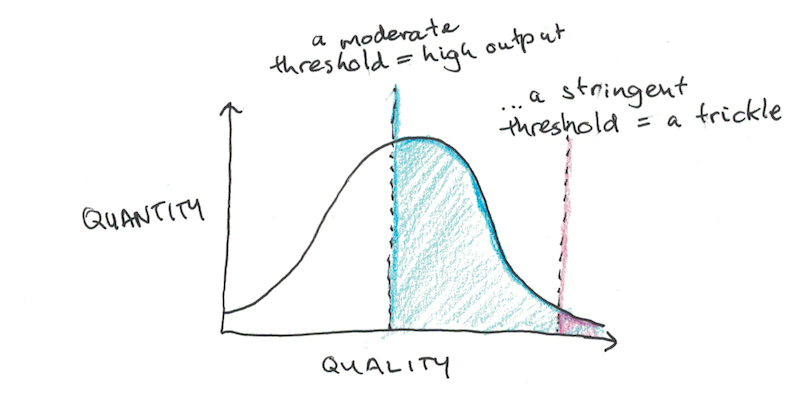

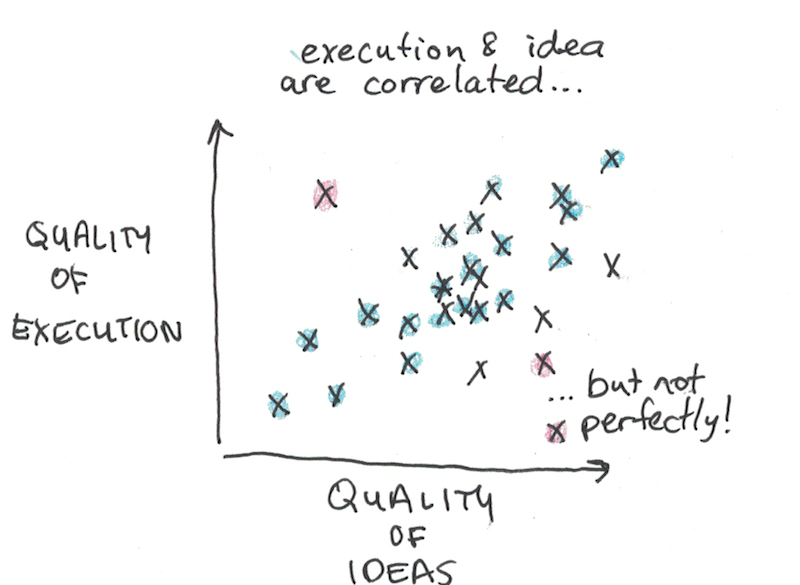

In short, the higher the “quality” threshold you set for yourself before you’ll make something, the less stuff you’ll make. Interestingly, this may not actually increase quality, since the predicted quality of an idea and how it looks when you start working on it are only somewhat correlated.

Identifying barriers that keep you from producing making stuff, and rerouting them is a big part of the process of making more things.

I’ll give an example from my recent experience. When I started this blog, I used to write five times a week. Add to that a few freelance gigs I had, plus any book projects, and it would probably be around 10,000-15,000 words per week.

Then, I began to notice something. I was posting too much. Readers weren’t able to keep up. I was persuaded that quality, not quantity, was really the thing to improve. So I cut down, I went from five to two posts, and then later to one post per week.

At first, quality did improve. But eventually it just settled at the same writing standard, just with lower amounts of writing.

Recently, I’ve switched back to my original 5x-weekly writing schedule. The main motivation was simply only posting once per week to the newsletter (with links to my other articles below-the-fold). This overcame my previous fear of writing too much stuff (or writing stuff that wasn’t my absolute best) because it might “use up” the newsletter slot.

You may find there’s other tricks you can use to shortcut your reservations about making more things.

Should You Follow This Approach?

Increasing output is just one approach you might take with your work. It’s not the only valid strategy, and in some cases, it may even be counterproductive.

An insider secret amongst famous artists is to produce less. Way less. Too much of your work out there means the value of each piece is lower. If you’re only making a few things, collectors will be more willing to pay premium for your art.

Similarly, I pursue quality-over-quantity in other aspects of my work, when it makes more sense to do so. I purposely write fewer books and make fewer courses than I physically could. I’d rather have a few options for people who want to go deeper than flood people with mediocre options. Free articles, on the other hand, don’t suffer from problem.

Being prolific therefore is not just something you “improve” but also a strategic choice you can use or avoid. Applied wisely, however, creating more can be enormously useful to you in your career.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.