My favorite book of last year was Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier’s The Enigma of Reason. I covered it in my book club as a podcast, but the ideas are so interesting that I wanted to take a second chance to explain them.

The basic puzzle is this:

- If reason is so useful, why do human beings seem to be the only animals to possess it? Surely, a lion who had excellent reasoning abilities would catch more gazelles? Yet human beings seem to be alone in the ability to reason about things.

- If reason is so powerful, why are we so bad at it? Why do we have tons of cognitive biases? Reasoned thinking is supposed to be good, but we seem to use it fairly little as a species.

Unraveling the Enigma

The answer to both of these puzzles, which has far-reaching implications for how we think and make decisions, is that we’ve misunderstood what reason actually is.

The classic view of reason is that it is simply better thinking. Reasoned thinking is better than unreasoned thinking. Being able to reason means being smarter—a kind of universal cognitive enhancement that is good for all types of problems. Sure, we don’t always use it and it can be slower than intuitive judgements, the classic view goes, but reasoning is always good.

Sperber and Mercier, argue, in contrast that reason is actually a very specialized cognitive adaptation.

The reason other animals do not possess reason is because they don’t have the unique environment human beings exist in, and thus never needed to evolve the adaptation.

The reason human beings often don’t use reasoned thinking is that our faculties of reason are actually much more restricted in their use. We use it only when necessary, and otherwise adopt the same strategies animals use to make intelligent behavior.

What’s the Point of Reason?

According to Sperber and Mercier, the purpose of reason, as a faculty, is for generating and evaluating reasons.

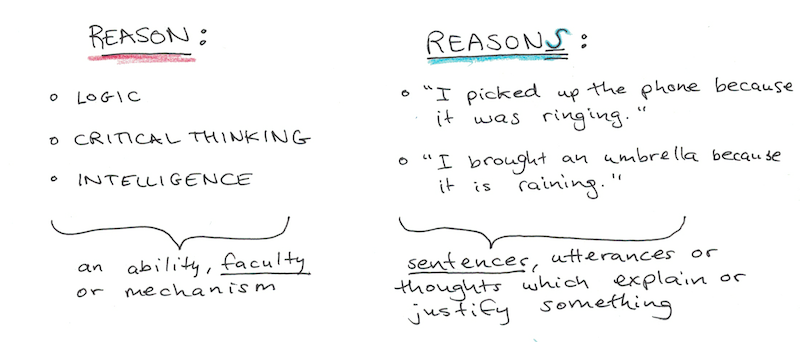

This may sound almost tautological, but these two words, reason and reasons, actually refer to very distinct things.

Reason is a faculty. An ability we possess. Near-synonyms might include logic, critical thinking or analysis.

Reasons, in contrast, are explanations, usually given in the form of sentences. “Because it is raining,” is a reason for bringing an umbrella outside. Reasons, such as this one, do not refer to the general capacity of human beings to decide to take umbrellas when it rains, but rather the explanations that justify such behavior to other people and oneself.

What Sperber and Mercier argue is that the human faculty of reason largely isn’t to create intelligent behavior. Instead, it serves to justify and explain that behavior. In short, we have Reason to create reasons. Those reasons aren’t mostly for ourselves, but to make our behavior comprehensible and justifiable to other human beings.

Animals don’t need this faculty because, without language, there is nobody to hear the reasons they might have. Human beings don’t use reason all the time, because, our decisions about what to do are mostly generated by other, intuitive processes, and reasoning is added after.

Mental Modules and How You Think About Things

A popular view of the brain is the modular theory of mind.

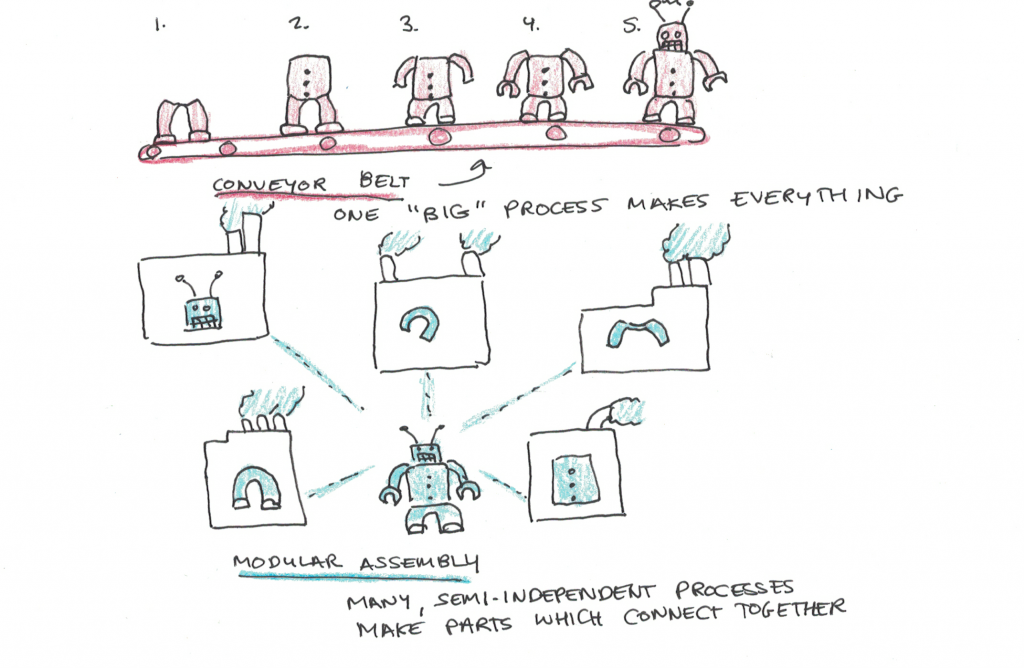

This view says that rather than being a unified whole, the brain is better thought of as broken down into distinct modules. Each module takes inputs from other parts of the brain, and gives outputs to other parts of the brain, and each module specializes to its own specific functions.

One metaphor for this might be to imagine comparing a big factory that makes gadgets from scratch, on a big conveyor belt. Now compare this to a bunch of separate companies that each make parts of the gadgets, and they get put together only at the end. Mental modules are more like this last picture, with each separate company being somewhat separate from the others, rather than a big unified conveyor belt of thinking.

Fitting in with this view, reason, according to Sperber and Mercier, is a separate mental module. This module has two functions:

- It takes situations and generates reasons for them. So if you were standing with your umbrella, and someone asked you “Why are you carrying that?” your reason module might generate a few candidate answers, before arriving on, “It’s raining outside,” as being a good one.

- It evaluates the reasons of others. In this way, you can also take the reasons given by other people and decide whether they are good or not. If I asked you why you’re carrying an umbrella and you said, “Because it’s Monday today,” that would not seem to be a good reason.

Important in this theory is that the decision to carry an umbrella itself needn’t be decided by the reason module. This might be a different module of the brain, that through past conditioned experience, generates the motor commands to grab your umbrella before leaving the house. The reason for why to carry the umbrella, in terms of an actual sentence or thought, may only occur later, upon being asked by someone (or anticipating being asked by someone).

Opaque Processes and Reasoning

One coincidence I find very persuasive in terms of arguing for this view of reason comes from machine learning.

A common critique of machine learning is that it is not introspectable. Meaning, if an algorithm decides to approve a loan, change a price or order a drone strike, human beings often don’t know why it made that choice. Even the designers of the algorithm itself often don’t know what were the causes of its decisions, even if it tends to make them accurately overall.

One proposed solution to this problem has actually been to make two systems. One makes the decision, the other trains itself on the patterns of the first system to generate “explanations” of the former. This way, a complete machine learning system could justify its choices.

The coincidence here is that this is exactly what Sperber and Mercier argue is how human brains actually work!

We also have a bunch of opaque algorithms that may be trained in ways not dissimilar to the machine learning algorithms. The fact that machine learning algorithms often describe themselves in terms of “neural” networks, uses their superficial similarity to the brain as a metaphor for their operation.

We too, also need to justify our behavior to outsiders so that it appears in keeping with how our society works. If we appeared to do things without any apparent reason, or worse, a reason that is not valid for that social situation, we may be seen as crazy or evil.

Thus, evolution fashioned us too with a second module, that takes our intuitively-arrived-at decisions and generates something that we can communicate with language to outsiders so that they can try to evaluate why we do what we do.

Implications of Sperber and Mercier’s Theory

There are too many implications of this idea to easily fit into a blog post. Best to read the book itself.

However, I want to showcase a few of the most important implications of this theory, if it is true.

1. Reasoning isn’t a big part of intelligence or (potentially) consciousness.

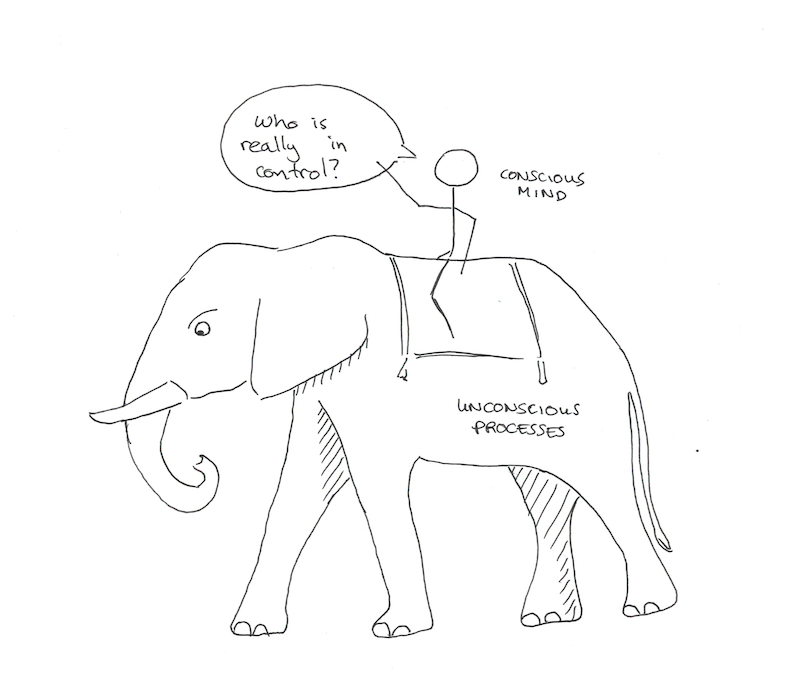

One common view of psychology is described as the elephant and the rider. We are the riders, loudly proclaiming where we want our behavior to go, yet it is really the elephant, the unconscious mind, that is the driving force.

This view has often been used to disparage the idea that we have much control over our lives or decisions.

Although the essence of consciousness is still debated, I think this new theory upends some of this view of the mind. In this view, there is no rider. Reason itself is just another module in the mind, providing specialized support for specific tasks. In other words, it’s intuitive, opaque processes all the way down.

A better metaphor might be of starlings. These birds fly in amazing patterns, but the behavior emerges out of each bird doing a smaller part. There is no bird who dictates the pattern of flight to others, like a rider might tell an elephant where to go. There is also no cohesive whole to ignore this order, like a willful elephant might ignore its rider. Instead, there’s a bunch of smaller parts (modules), all doing their own purposes, contributing to a more intelligent behavior at a larger level.

2. It’s possible to have smart decisions, but not be able to have reasons for them.

In a classic view of reason, having no reason for an action makes it almost certainly a bad one. Unless it happens to randomly be correct, there’s no reason to trust it if there is no reason behind it.

Sperber and Mercier, in contrast, completely flip this view. If reason exists to generate reasons, then there are potentially tons of smart decisions that we struggle to generate good reasons for. Therefore, ignoring one’s reason and acting without it, is not necessarily maladaptive (unless you get confronted about your behavior by others).

I don’t think this implies we should make every decision on intuition alone, but it does put a big hole in the project of “rationality” as a self-improvement goal. If rationality is really mostly about rationalization, then the idea of working hard to make more of your behavior in line with your “reasons” is a fundamentally flawed one.

3. We are smarter when we argue than when we think alone.

Sperber and Mercier call their theory the “argumentative theory” of reason. This is because they claim that the function of reason is to provide socially justifiable reasons for beliefs and behaviors. This also explains why we have a strong my-side bias, looking to justify our beliefs rather than challenge them—this is what reason is actually for.

However, the power of reason, and why reason produces such wonderful things as technology, science and human progress, is that collectively, our individual weaknesses cancel out. You may not persuade your opponent in a debate, but the audience is listening. In the end, good reasons win out over bad ones in the broader sphere of discussion.

4. Feedback loops may explain the role of classical reason.

This explanation may seem like it dismisses too easily the focal example of classical reasoning: smart people thinking carefully to arrive at a hard-won, but brilliant, insight.

However, when we see that reason can both generate and evaluate reasons for things, this forms a potential feedback loop. You can take the reasons you generate yourself and then evaluate them. If you expect push-back, you may reject those initial reasons and dig deeper to try again. This may even push you to change your intuitive beliefs, if you are unable to come up with a suitable justification.

This actually happens all the time when you have to explain something to a skeptical audience. You may rehearse several different explanations before settling on the one you think is the most justifiable reason.

This back and forth, combined with the ability for a reason module to override intuitively-made decisions, provided they can’t be sufficiently justified, may explain, in a dynamic sense how Sperber and Mercier’s theory of reason flowers into the classical reason under specific circumstances.

5. You will reason better if reasons are harder to provide.

Better, this theory also explains why this kind of deep thinking is so rare: normally we aren’t dealing with such a skeptical audience! We’re satisfied with sticking with the first reason that pops up, not searching and evaluating and possibly even changing our beliefs when those first intuitions are shown to be unjustifiable.

This may also explain why scientific communities reason so well. The audience is extremely skeptical, and sets narrow constraints as to what kinds of reasons count. This makes such narrow wiggle room, that often it is easier to override an intuition, than to provide an acceptable reason for a bad intuition.

This may also give a potential improvement tip for performance in reason-based domains. The higher standards you imagine your audience will have, the better your thinking will be. It will force you to go over and over your thoughts with a fine-toothed comb, rather than simply state your intuitions and leave it at that.

A corollary for this, however, might be that if the constraints are too narrow for reason, it may lead to rejecting “good” answers, that don’t fit the reasons they contain. Dogmatism may be an inevitable side-effect of reason as the structures that force reasoning into specific channels may ultimately divert it from the truth.

Concluding Thoughts

In the end, our minds are not separated into a war between a ruling, but often frail and feeble, reason, and a willful unconscious. Instead, it is split between many, many different unconscious processes, each with their own domains and specialized functions, with reason standing alongside them.

In some senses, this is a demotion of reason, from being a godlike faculty that separates us from animals, to being just one of many tools in our mental toolkits.

But in another sense, this is a restoration of reason, since instead of appearing like sloppy, feeble and poorly-functioning faculty, it appears as if reason does exactly what it was designed to do, and it does so very well.

Although there are many implications of this idea, it is how it changes how we conceive of ourselves that matters to me most of all. If we are not the rider on the elephant, but the murmuration of starlings, then our selves are both more powerful and also more mysterious than they first appear.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.