One of the common questions I get asked about my ultralearning projects, such as the MIT Challenge, is how to keep up hard mental effort for long periods of time.

During that project, for instance, my starting point was to study for 11-12 hours per day, five days a week. Starting at six in the morning, I’d wake up, and begin watching lectures, doing problem sets or otherwise preparing until five or six at night.

In the Year Without English, my friend and I made a point of not speaking English to learn languages. Although the difficulty eased as we improved, each new country put us in a situation where we were strained non-stop for a few weeks, as our abilities were too minimal to say almost anything without a dictionary or translation app.

Mental stamina—of continuing your focus on hard, intellectual problems for weeks or months at a time—is an essential skill for learning important things. If you surrender to frustration and fatigue easily, then you’ll chronically be fighting a war with yourself to do the work you need to.

Strategies for Cultivating Mental Stamina

Since building up my endurance on tough mental problems has been an important goal of mine for awhile, I’d like to share some of my strategies that have worked for me in reaching this goal. Experiment with all of them, and focus on the ones which work best for you.

Strategy #1: Create an Obsessive Quest

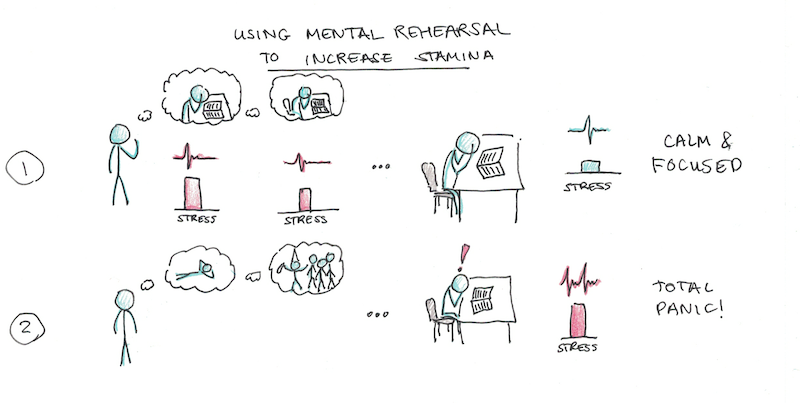

In my mind, mental stamina is as much about preparation as it is about endurance, after the fact. In all of the projects where I successfully sustained a long period of mental work, I also spent considerable time obsessing, rehearsing and preparing for those challenges.

The MIT Challenge began in September 2011, but had begun thinking about it, planning and visualizing it as early as March of that year. Therefore, when the classes hit me, and I was pushed to study many hours per week, the strain and fatigue didn’t feel nearly so difficult.

For my thirtieth birthday, I went bungee jumping with some friends. The surprising thing is that I used to be terrified of heights. Even as a teenager, I’d avoid standing too close to windows in tall buildings, or my palms would get sweaty. So jumping off a gorge on my own was definitely a tough mental challenge.

Before the jump, I was worried that I would freeze when I stood by the edge. So, for nearly a week before, I imagined standing and taking the jump. Each visualization had my heart racing, yet, when it came time to finally jump I didn’t freeze. (I didn’t end up visualizing the fall though, so that ended up being much scarier than the initial jump had been!)

This strategy of visualizing and mentally rehearsing anxiety or stress-inducing moments has been demonstrated psychologically to help with performance. The problem with mental stamina is that you’re going to have feelings of strain, frustration or overwhelm. But if you start mentally planning for them well ahead of time, when they actually do occur, they’re much more manageable.

Strategy #2: You Can Always Just Sit

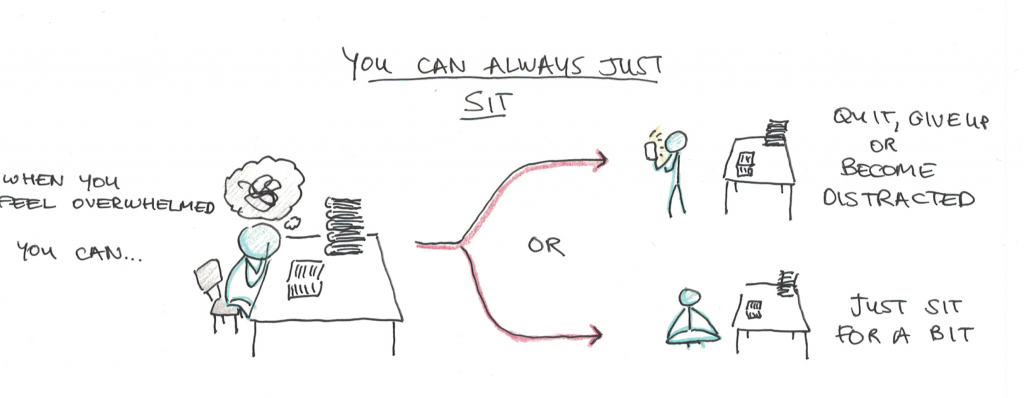

In encountering a frustrating problem, there’s an immediate impulse to flee. Our nervous system is hardwired to handle threats as if they are tigers, crouching in the bushes. Yet, such responses are not particularly helpful when the problem to overcome is calculus.

One solution I’ve found particularly helpful in these moments is that whenever I felt overwhelmed by a problem, I could always just sit there. Meaning, I could temporarily shut off mentally from the problem and just sit, quietly.

While this is obviously an option available to all of us in mentally straining situations, it’s not usually our first reaction. We want to get up, do something else and distract ourselves with phones and Facebook.

Just sitting, however, reminds you that the strain you face is largely an invisible one. It’s not a tearing of your muscles or pulling of your joints. It’s an anxiety about your upcoming test, a frustration in a problem you don’t understand or a fatigue from working hard all day. Releasing yourself from those emotions, just for a moment, and doing nothing, can help you get a better grip on them.

Strategy #3: Create Positive Feedback Loops

Although mental stamina was a key ingredient in all of my challenges, the truth is, most of the time they flowed fairly well. I didn’t feel frustrated, anxious or upset, just pleasantly challenged.

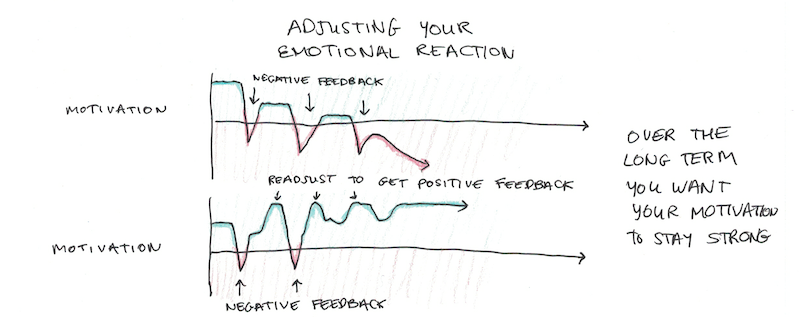

Thinking about those moments, I think a big reason why they felt that way was because I had built up a cycle of solving the problems I faced. When I’d encounter a subject I didn’t understand, I didn’t panic, because I had succeed to understand similar concepts before. Similarly, when there would be a hard test, I felt confident that I could master the techniques.

This confidence cycle is important for many things in life, but I think it’s particularly important for your stamina. When you feel encouraged to go forward, the effort required to keep going is far, far less than when you feel beat down at every turn.

Cultivating these positive loops is part challenge selection and part expectation. Selection, in that you should pick activities and tasks that challenge you, but don’t overwhelm you. If you feel totally put off from even trying, pick something a little easier and try again. Increase the challenge until you find it straining, but not completely unpleasant.

Expectations, however, are also quite important. Because I approached my challenges under strange constraints, I often didn’t expect to succeed. The status-quo for tackling a class in five days, or a language in three months, wasn’t success, so when I felt frustrations or difficulties these seemed totally normal.

In contrast, students who struggle in school systems often think to themselves, “Why is it so hard for me? If I’m struggling so much, I must be dumb.” This attitude encourages you to give up and find something where you’re better suited, even if almost everyone in the class privately feels this way!

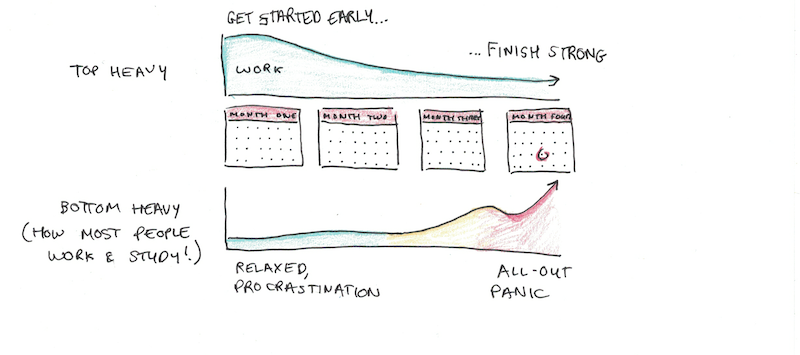

Strategy #4: Make Your Attack Plan Top-Heavy

In all my projects, I expected to get tired. I expected to lose motivation and start to be a little less willing to work hard. But, I tried to compensate for this by making my initial plans a bit harder and faster-paced than expected. Thus, as I naturally got a little more fatigued, what I needed to stay on schedule got a little more slack.

In the MIT Challenge, my initial starting pace was one class per week. At thiry-two classes over a fifty-two week year, this is slightly faster than necessary. So later on, I took classes more slowly, and spread out over time.

It turns out that this worked out perfectly, because my initial 11-12 hour studying sessions were unsustainable. After about ten classes, I was getting more fatigued, and I couldn’t sustain them. Switching to seven or eight hours was necessary, but also possible because of my initial plan.

Strategy #5: When in Doubt, Shorten the Time

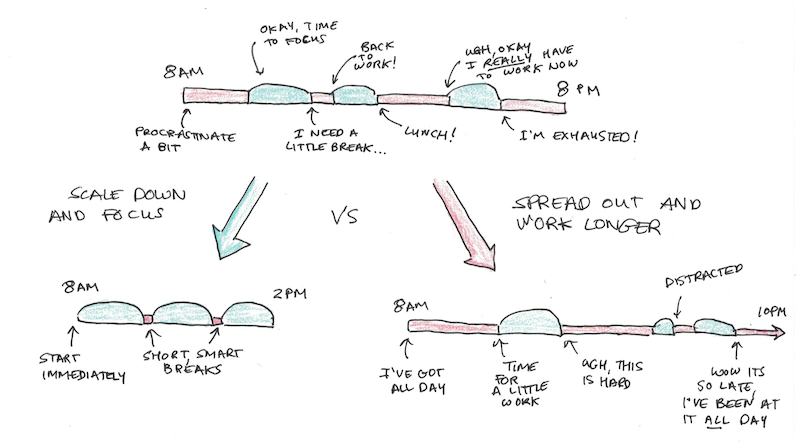

A common story I’ll hear is from students, panicking because of an upcoming exam, studying for every waking moment. They will tell me that they’re studying fifteen hours or more, seven days a week, in order to reach their goal. They’re cutting sleep, losing exercise and pulling out their hair just to stay on track.

Except, in the same email, this same student will complain about procrastination. That they can’t be motivated to continue. That they easily get distracted and can’t seem to focus on their studies.

So which is it? Do you study all day or are you procrastinating all day?

Somehow the internal contradiction between these two statements isn’t obvious to the student. To them, they think that their tendency to procrastinate should mean they need to work even more, to make up for their own flagging willpower.

This is entirely backwards. Your stamina is what it is. You can take the above strategies to extend it, certainly. But some goals will naturally cultivate within you a steadfast endurance, and others will be painful and require prodding. Some people may have more natural mental stamina for some tasks than others.

The solution to continuous distraction, procrastination and poor quality attention isn’t to inject more hours into your schedule, but to apply less. Concentrate your studying into shorter bursts of time and give yourself more time for rest, sleep, exercise and self-care. Force yourself to study only five or six days a week, instead of seven.

Then, from this more limited, and constrained starting point, aim for total absorption. Start immediately when you tell yourself to start, eliminate any outside distractions and work on the hardest, most challenging mental problems.

Once you successfully work with pure concentration for the time you allocated for yourself, you can try stretching the timeframe a little more, but not before. If the concentration time you’ve allocated is not enough to succeed in your goal, then you won’t succeed in your goal. I’m sorry to say that, but switching from a dedicated and pure focus, to a hazy and haphazard one over slightly more hours certainly won’t do the trick, so don’t bother.

The only chance you have of reaching the finish line is to start from a base of relatively high-quality concentration and build up, rather than one full of procrastination, guilt and endless distraction to which you respond with an even more demanding schedule.

The Merits of Mental Stamina

These metacognitive strategies for mental stamina are not the complete picture. Natural aptitude, interest and environment all make a difference and, yet, are somewhat outside your control.

However, mastering whatever you can is still enormously beneficial. Mental stamina is essential for success in school, work or any intellectually demanding task. The higher your threshold for quitting due to frustration, the more things you can master.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.