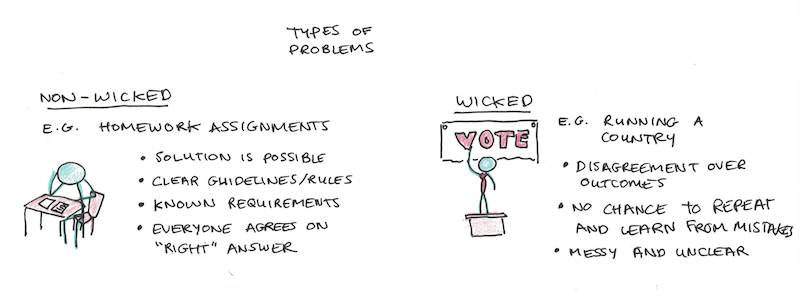

Wicked problems are problems that are, “difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize.”

The classic example of a wicked problem is running a country. The problem is wicked because, nobody can even agree as to what counts as a solution! One person’s solution is another’s failure. Values conflict, and even if we could agree on that, it’s hard to know whether a plan was as effective as it could have been.

Non-wicked problems are typical in school. You’re given a setup of pulleys and incline planes, and asked to calculate friction. You’re given an essay, told how many pages to write, what to write it about and when to submit it. The constraints are known, and even if success is difficult, it’s possible to know whether you’ve passed or failed.

Real life, in contrast, is full of wicked problems. Learning to deal with their wickedness is essential to the art of living.

Dealing with Life’s Wicked Problems

The first step to dealing with wicked problems in one’s life is recognizing that they exist. Many people prefer to pretend that all wickedness can be removed by some elegant formalization of the problem—and that those who disagree are wrong.

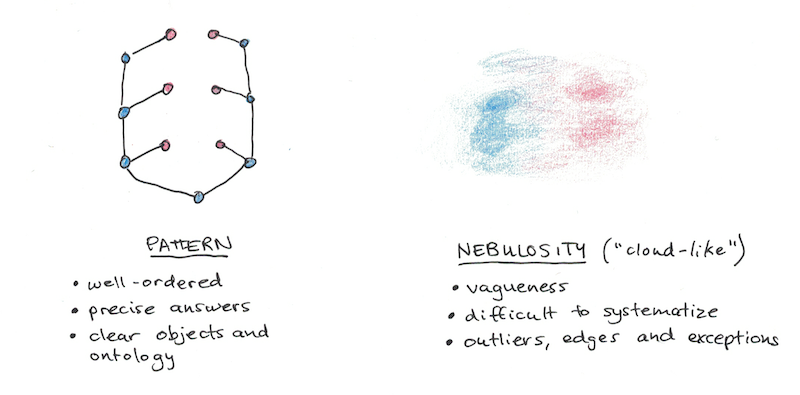

Philosopher and former AI researcher David Chapman argues that the things we experience in life always have a mixture of recognizable patterns and amorphous nebulosity. Although we always experience both, it’s a common human reaction to reject the nebulousness of things and want to insist that there really is a deeper pattern that we do not yet understand.

Wicked problems undermine this view because they are, by nature, not formalizable in a way that everyone will agree upon. Although you can take a wicked problem like running a country, protecting the environment or becoming “successful” and transform it into a non-wicked problem—enacting Communism, setting zero emissions targets or earning a lot of money—such transformations risk sweeping away some of the original problem.

Ignoring nebulosity doesn’t eliminate wicked problems, it merely ignores their wickedness.

A Proof of Wickedness

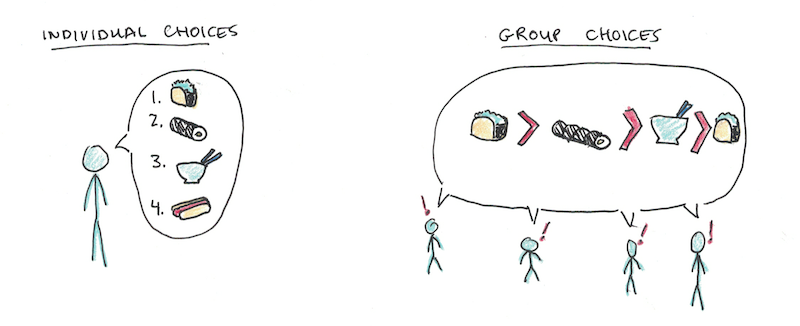

The wickedness of social problems may be a mathematical inevitability. Kenneth Arrow showed in his 1951 book, Social Choice and Individual Values, that in some cases it can be impossible to enact a solution that most people will agree with.

Consider an individual choice—say where to go eat lunch. You may prefer Mexican, but if you can’t have that choice you’ll go out for sushi, Thai or last, eating at the hot dog stand.

Suppose when you go to the Mexican restaurant, you find out it is closed. Common sense would say that you should want to go to sushi now, not eat at the hot dog stand. When your #1 choice was eliminated, you should go to #2, not #3 or #4.

Except, when you consider groups of people, say five friends all trying to eat lunch, such things can occur! No matter what mechanism you use to make a decision (rank-ordered preferences, first-pass the post voting, etc.) it’s possible to have these inconsistencies.

Wickedness, therefore, can show up even in simple matters as choosing a voting system! The naive expectation is that if we had the right system, these kinds of weird paradoxes would be eliminated.

Life’s Wicked Problems

Social problems are frequently wicked, for the very reasons Arrow illustrated—it’s not clear how to take a bunch of individual preferences and aggregate them into a single decision without creating some surprising inconsistencies.

However, you face wicked problems in your private life as well. Problems where:

- What counts as a solution is hard to define.

- The problem can never be definitively solved.

- Even if you are successful, it’s not clear what would have happened without your action. Therefore, it’s hard to know whether the actions you took were best.

- You can only attempt the problem once. Therefore you can’t learn to solve the problem.

In this sense, deciding whom to marry, whether to have kids, which career to pursue, where to live and what to value in life, are all problems with elements of wickedness. While we are forced to answer these questions at some point, what counts as a correct choice may be hard to say.

Overcoming Wicked Problems

There’s no step-by-step solution to wicked problems. That’s by definition, not out of ignorance. Yet, there are tools. These can’t be said to guarantee better solutions to the problem, or ensure you’ll arrive at the correct choice, but do tend to work better.

Some of these tools include:

1. Cultural learning.

Individually, you may not have the ability to live your life over and over again, thus learning how to make correct choices for the decisions that can really only ever be made once. However, collectively, our culture functions in this way. Adaptive social strategies persist. Less effective solutions fall away.

The defaults provided by your culture (or other cultures, if you search more broadly) to the wicked problems life foists upon you, can offer solutions that may not be obvious from your personal experience alone.

2. Multiple perspectives.

If a single formalization for wicked problems is too simplistic (e.g. “I want to be successful” = “Make lots of money”), then making several such formalizations can give you multiple perspectives to judge the problem.

Although different formalizations aren’t guaranteed to arrive at the same answer, there will be some problems where most ways you formalize them land at similar suggestions. Thus you can more safely approach your problems with one way of thinking about them, since different assumptions point in the same direction.

Read my article here about twenty-five different thinking tools to get an idea on how different perspectives can help solve difficult problems.

3. Genuine choice.

If one option you have of many is indisputably better, then what does it really mean to say that you chose it? If a single career choice is the obvious correct one for you, then, to some extent, there isn’t really much of a decision needed to pursue it.

In this sense, the wickedness of life is also what allows for creativity and freedom. If all choices have a systematic method for arriving at the “correct” answer, then there’s no real need for human judgement.

Genuine choices, those which don’t have clear answers or evaluation criteria, may be frustrating and puzzling, but there also a chance at creativity and self-expression. If all art could be judged by a perfect rubric, determining its value, would it still be art? Similarly, if all life problems could be dissolved into a simple logic puzzle, would there be any life in them?

Regardless of how you choose to approach the wicked problems in your life, admitting their existence may be the first step to embracing them.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.