The basic process for building all habits is basically the same: you repeatedly condition the behavior you want, over time, until it becomes automatic.

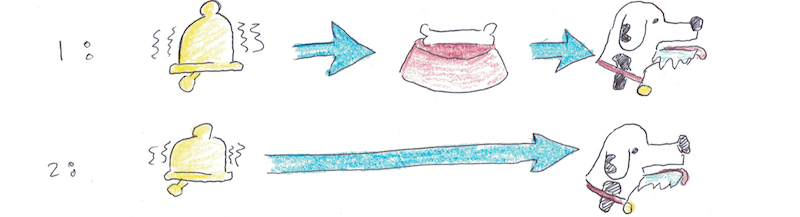

There’s two main ways you can condition a habit. One is through classical conditioning. This is simply a paired association with a trigger and a behavior. Going to the gym after you wake up each morning is this kind of habit.

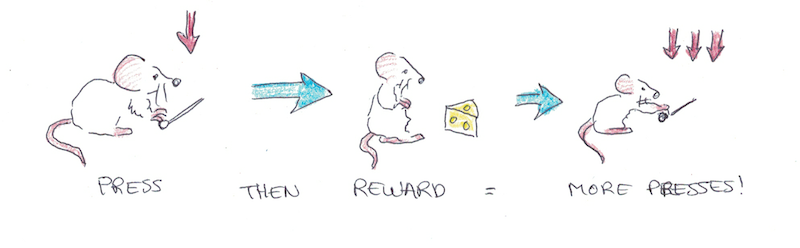

The second way you can condition a habit is through operant conditioning. Here, you not only associate a trigger with a behavior, but you reward that pairing. Reinforcement (by adding rewards or removing pains) can accelerate the habit-forming process. At the gym I go to, there’s a pool and hot tub, so a quick soak post-workout made the overall experience of going to the gym more pleasurable, and thus easier to keep as a habit.

In addition to the different conditioning strategies (classical and operant) there’s also a ton of little things you can do to smooth the process to habit formation. James Clear’s excellent book, Atomic Habits, is a good guide to many of these.

In this article, however, I’d like to look at a different aspect of forming habits, namely the mental rules or commitments you use when trying to form them.

Seven Different Rules for Making Habits

No habit starts out automatic. Instead, there’s a deliberate period, where you must consciously apply yourself to make a certain behavior your default.

During that time, there’s a bunch of different ways you can regulate your commitment. These are things like, “Do X every day” or “Whenever X happens, I do Y.” I’ve tried a ton of these different rules personally, so I’d like to talk about what I think are their varying strengths and weaknesses so you can pick the approach that works best for you.

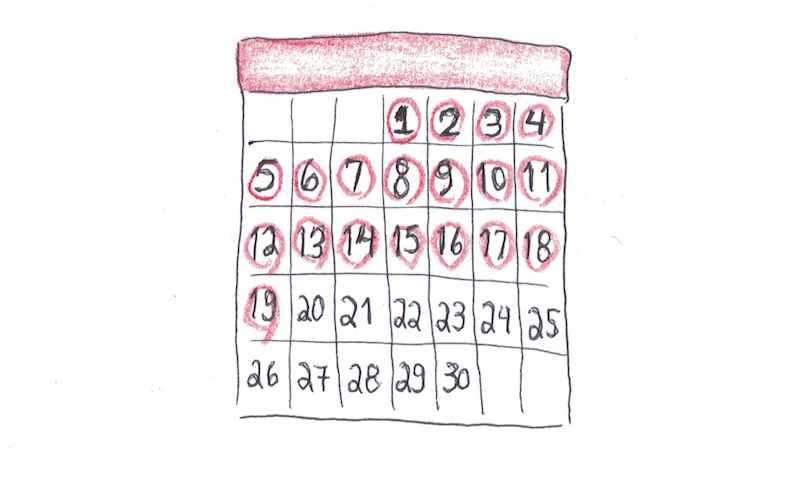

1. The 30-Day Trial.

This was the first approach I ever encountered to forming habits. I learned it from Steve Pavlina, although the technique predates him in various guises (21-day trials, 10-day trials, etc.)

The basic approach is simple: you commit to some change for thirty days straight. This could be something you actually do every day, like going to the gym, or another rule you follow like not drinking alcohol.

Once the thirty days are done, the concept goes, you’re free to go back to your old ways. The point of this framing is that the thirty days should be seen as an experiment. You can challenge yourself to something you might otherwise be afraid of setting as a lifelong commitment. The reverse of this is that having spent thirty days applying a new behavior is often enough to convince you to stick with it.

Pros:

- Can handle more significant/difficult behavior changes you might be unlikely to start with a perpetual commitment.

- Fosters an experimental mindset. “What if?” rather than assuming you already know what’s best. – One month is short enough that planning is rarely a big issue.

Cons:

- 30 days probably isn’t enough to actually make something a habit, especially if the behavior change is difficult.

- Without a long-term plan, many 30-day trials will revert back to the original behavior. A month without drinking often ends with a few beers, not a commitment to lifelong sobriety.

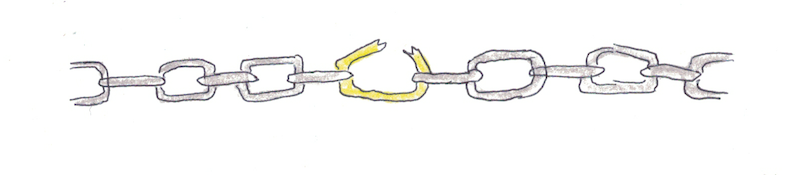

2. Don’t Break the Chain.

“Don’t break the chain” is a slogan (often attributed to comedian Jerry Seinfeld) for sticking to any important behavior. The idea here is that you want to keep track of how many days in a row you’ve successfully followed your habit. As your chain gets longer and longer, you become increasingly committed to the habit.

I’ve applied this myself to many habits from daily push-ups to flossing. I do find it works really well for maintaining a commitment over a long time. I currently use the app Done, to track my DBTC habits.

Pros:

- Maintains habits over a longer timeframe than a 30-day trial.

- Better for things you already do (or are easy to do) but you’re not as consistent as you’d like. (30DTs are often better for more dramatic changes to your behavior)

- The longer your chain, the more serious your commitment. I can remember doing pushups when I was feeling quite ill, just because I had a few hundred links in my chain and I really didn’t want to break it. That’s a powerful commitment device.

Cons:

- Accidental slip-ups or situations where your habit becomes impossible can collapse your motivation.

- More awkward with difficult habits. If it isn’t easy to do every day, you’ll slip up enough that your chain will rarely get long enough where your commitment is strong.

- Many habits don’t work on an easy daily or weekly interval.

3. Never Miss Twice.

James Clear, who I mentioned wrote a great book on habits, has a strategy for working out where he aims to not miss a workout twice in a row. This is different from the DBTC approach where a single slip-up can undermine the entire habit.

For this, the goal is to do it every day (if possible) but if you miss a day, you must do the habit the following day.

Pros:

- More forgiving than DBTC, which means it’s easier to keep up for longer stretches with harder habits.

- Since you’re keeping track of misses, rather than completes, it’s a little easier to handle on an irregular schedule (say working out 4x per week).

Cons:

- More slack also means more slacking off. DBTC works so well also because it’s so rigid. You’ll be much more likely to take days off unnecessarily if you know it’s only two-in-a-row that count.

- Habituation works best when the trigger-behavior link is total. If you sometimes do X, and sometimes don’t, it will take longer to make the association automatic. DBTC will do this, but allowing yourself gaps might not.

4. Pretraining.

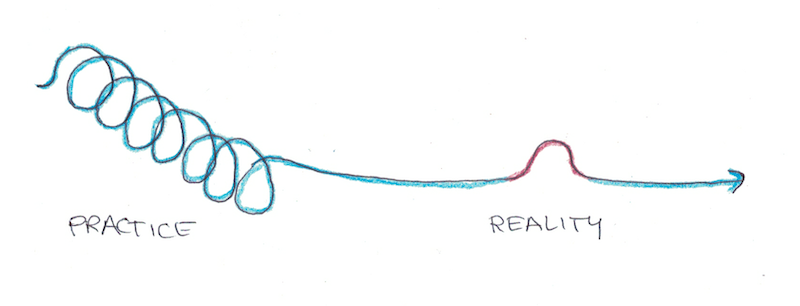

Pretraining means practicing the habit a bunch of times in an artificial situation so that it occurs more automatically in real life.

I’ve used this before when trying to condition myself to wake up automatically from the alarm, and not hit the snooze. I practiced by taking a short nap in a darkened room, setting the alarm for 5 minutes and then, when it sounded, getting up right away. Repeat this 10-20 times, especially over a few sessions, and you’ll be more likely to override your unconscious urge to fall back asleep in the morning.

Pretraining is somewhat uncommon as a tool for typical habits, but it is extremely common when the trigger is some kind of question and the behavior involves a skill or knowledge. In those specific cases, though, we tend to call pretraining “studying” and habituation is called “learning.”

Pros:

- Useful for situations where you think you won’t be able to consciously control your reaction in the real situation without practice.

- Aids when the behavior you want to perform requires skill or knowledge you might not possess without practice.

Cons:

- Real and practice situations often differ in important ways, so the practice may not fully transfer to the real situation.

- Practicing multiple times in the same session (massed practice) is known to have a weaker impact on long-term changes to your behavior than spreading them out. Since spreading the behavior out is guaranteed in more typical habit-creating strategies, this is a potential drawback of pretraining.

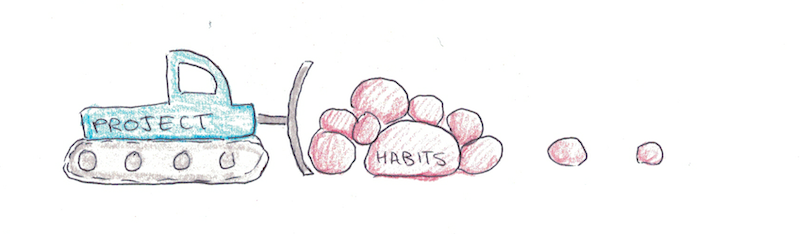

5. Project-Driven Habits.

Another approach is to ignore the process of creating habits altogether and simply focus on a project that will force them to occur.

I changed a ton of habits during the MIT Challenge. I changed even more during the Year Without English, when my friend and I had to stop using English to communicate. However, the habit changes weren’t explicit. Instead, they were the byproduct of trying to accomplish something else.

I find a similar thing often happens with ultralearning projects. You might learn something intensely, but not call it a “learning project” because what you’re really trying to do is start a business, create a website or prepare for a new job. Habits, like learning, are always in the background, but it’s a choice about whether to work on them explicitly or implicitly.

Pros:

- You can often change multiple habits at the same time with less overhead. Normally, the goal of waking up early, making your lunches ahead of time, getting into deep work right away at your job and cold-calling people to network would be difficult to coordinate as separate projects happening simultaneously. However, if you are starting a new business, those habits might piggyback and come automatically, just by having sufficient motivation for the main goal.

- A lot of habits are superfluous and don’t drive results. Focusing on projects first can help you be flexible about adopting and dropping habits based on what works, rather than assuming you already know.

Cons:

- Once the project is done, the habits may go with them.

- A project can often eat up or push out other good habits. Getting really excited about a work project may interfere with a healthy eating habit if you run out of time to cook for yourself.

6. Tattletale Tactics.

This strategy works by deputizing others to enforce your habit for you. The classic example is the realtor who bought a billboard with his face on it saying, “If you catch me smoking, I’ll pay you $20,000.”

The stakes don’t need to be so big, or even involve money, to work, however. If you have an annoying habit of interrupting people when they talk, you might ask your friends to point it out to you next time you do it, thus creating social pressure to stop.

This strategy can also work for positive habits, not just breaking bad ones. You might have a gym partner and go in with the deal that if either of you skip a day, you have to buy the other person dinner.

Pros:

- No formal rules or mechanisms are required, just the social pressure from the outside.

- If you find yourself constantly breaking your own commitments, you may not have the track-record to take your own commitments seriously. This may be the only tool you can use to effectively control your behavior.

Cons:

- Requires others to care. Most people won’t care about your behavior as much as you should, so this can backfire if the incentive to tattle is weak.

- Doesn’t work if others aren’t watching you while you perform the habit. How can your friends know whether you clean your house regularly if they don’t live with you? Or floss your teeth?

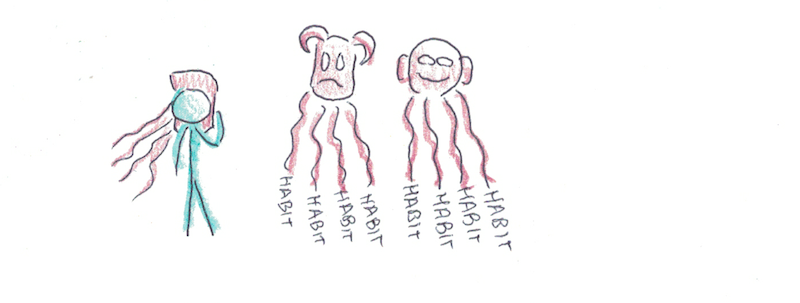

7. Identity-Driven Habit Changes.

Another strategy is to avoid thinking about changing a habit, but instead think about changing your self-conception. In other words, you don’t quit smoking directly, but you stop because you’re a healthy person now and you don’t put toxins into your body.

This strategy is not mutually exclusive with the ones above, but it can be a standalone approach to habit change by constantly reaffirming a new way of describing yourself and the emotions you attach to certain things.

My own experience is that this can work, but it usually works because a certain identity change was already occurring on the inside for awhile before manifesting into new behaviors. When I first became vegetarian (I’m now mostly pescetarian), I had read a ton of books about it, and it changed my feelings about eating meat sufficiently that by the time I stopped, there wasn’t much tempting about it.

Similarly, if you view yourself now as an entrepreneur, not an employee, that may change a bunch of habits automatically long before you actually quit your job. I’ve also seen many new parents make a similar transition when they turn themselves into self-professed saints overnight for the good of their children. Although such transformations can be annoying if they don’t come with self-awareness, they do often work.

Pros:

- Identities, like projects, are packages of habits, so you can often change a bunch in one deliberate effort rather than piecemeal. “I’m a healthy person now,” can trigger eating better, exercising more and quitting smoking and drinking all at once.

- If successful, these can make not following the habit unthinkable. A complete identity change may make the old behavior so unpallateable that you’re unlikely to ever go back.

Cons:

- Often requires that your self-conception has been changing for years, and that you’ve built up a healthy dislike of your old behavior that simply hasn’t manifested yet. If you’re trying to change your identity but you still really like the old you, the change won’t last.

- Hard to plan for and pull off. While identity-changing can be triggered, in certain conditions, I’m skeptical that it can be initiated purely on its own.

What Approach Do You Take to Changing Your Habits?

I’ve listed seven of the approaches I’ve used. What are yours? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.