James Clear recently tweeted about the importance of carefully cultivating your tribe:

He’s not wrong. Being surrounded by the wrong culture can definitely impede your progress.

However, there’s more nuance to the idea than that you’re simply the average of the five people you spend the most time with.

In one of my favorite books of all time, Harvard anthropologist Joseph Henrich, makes a compelling case that it’s not true that people merely copy the behavior of those around them. Even more, the fact that we don’t follow this simple approach may underlie the source of all human progress.

Who to Copy: Prestige and Dominance

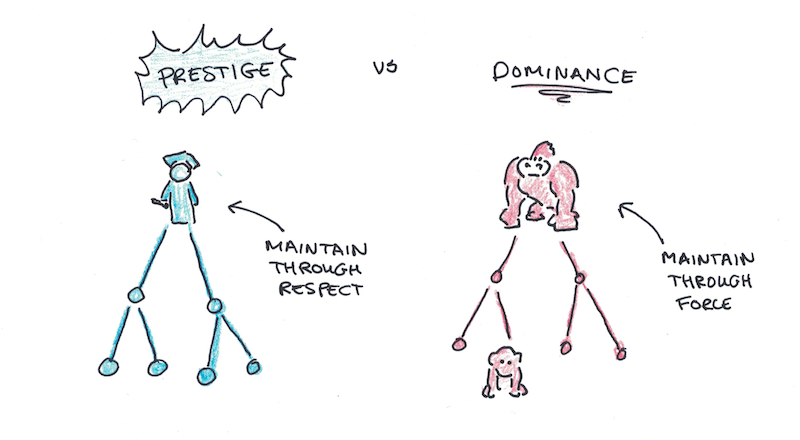

Many animals exhibit what’s known as a dominance hierarchy. The alpha picks on the beta, all of whom pick on the omega. These hierarchies are asserted through force and they exist in human beings as much as they do in others. Bosses, commanders and kings all formalize the notion of a dominant individual being higher up in status.

Interestingly, however, human beings have a second, separate status hierarchy that doesn’t seem to exist in other animals: prestige hierarchies. A prestige hierarchy isn’t maintained through force and alliances, but through respect. Artists, academics, celebrities and intellectuals are higher up on prestige hierarchies.

When anthropologists study human beings across different cultures, what they observe is not blind copying of random individuals that surround them. Instead, it’s copying of prestigious individuals.

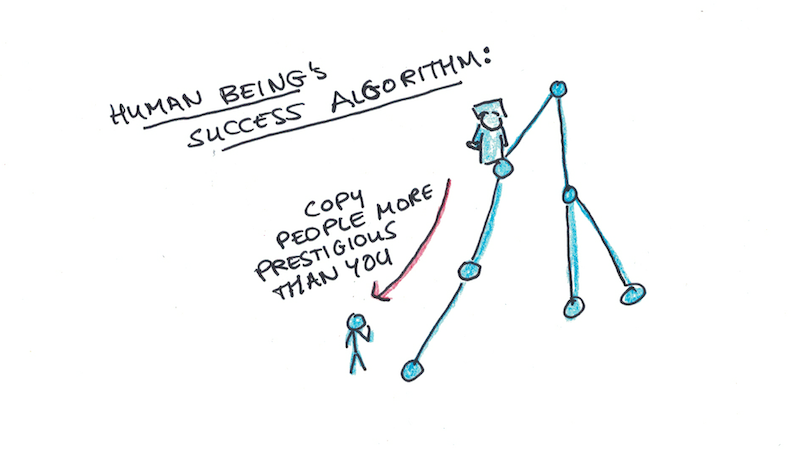

This copying also seems to be happening at a level beneath explicit rationales about what works. This means that people will copy things even with no argument about why X is better than what they were doing before, but simply because someone prestigious seemed to be doing it.

One example, involving hunter gatherer tribes, found that after a more successful tribe (= more prestigious) had painful rites of passage for boys to be seen as men in the tribe, many other tribes spontaneously adopted the same kinds of rituals. This kind of copying, therefore seems hardwired instinctually, rather than simply a product of reasoning about the cause of success.

We try to do what the cool kids do, without even realizing it.

The Power of Prestigious Copying

Henrich argues extensively in his book that this simple mechanism: copy prestigious people (or groups) may have been one of the principle mechanisms behind the invention of culture and how human beings surpassed our hominid ancestors.

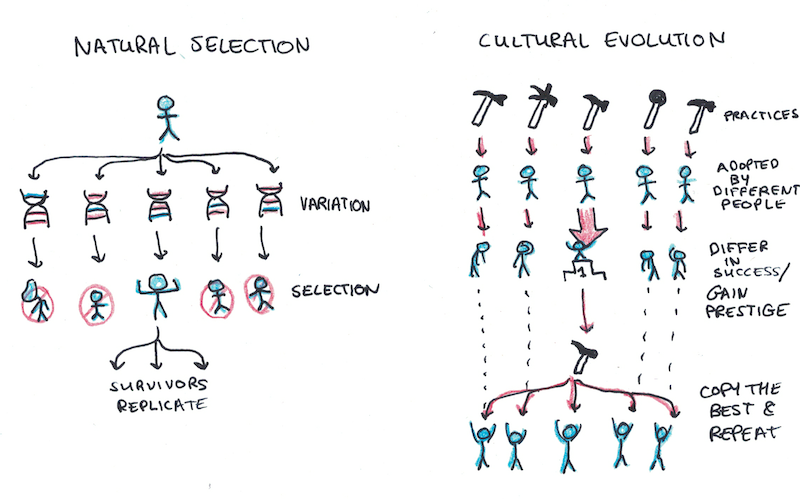

Prestigious copying works like natural selection, except instead of inheriting genes through reproduction, you copy behaviors from other individuals. Since people tend to copy all the details, not merely the underlying rationale, this fidelity means that complex behaviors can evolve culturally and propagate even if people don’t know why they work.

It’s likely true, therefore, that our cultures have embedded in them countless beneficial strategies and behaviors that we don’t have a clear reason for why they work. They work the same way that a cat can hunt without understanding its own digestion, because a process of replication and selection generated it, rather than deliberate engineering.

When Copying the Most Successful Backfires

For all the power of copying, however, it can backfire. Like the painful manhood rituals of the tribesmen, just because successful people are doing something doesn’t mean it’s actually useful.

In fact, the opposite can be true. Successful people often engage in what’s known as counter-signaling. This is when you do things that are actually costly, just to show you have the ability to pay for them.

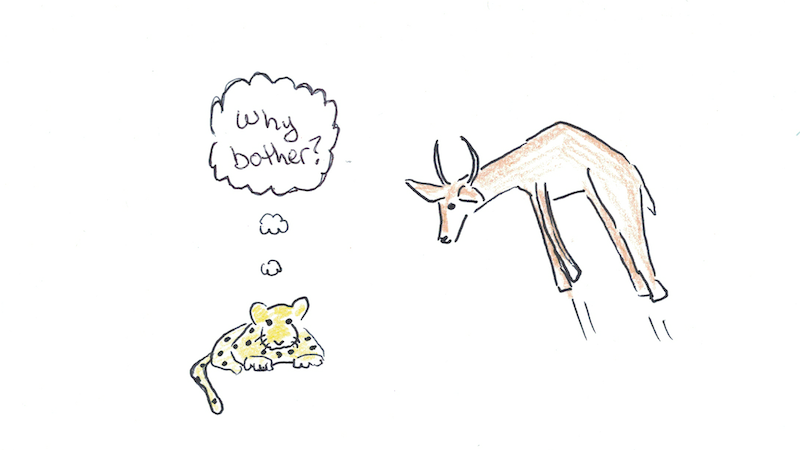

A gazelle that wastes energy by leaping straight up in the air after spotting a crouching leopard could have used those calories for running away. Instead, however, it wants to say “look, I’m so fit you shouldn’t even try to chase me.” The peacock has such impressive plumage, not because it helps him survive, but because he has to be healthy to survive, so the peahens will pick him.

Signaling is pervasive everywhere, thus our instincts to blindly copy prestigious individuals can backfire if we copy costly signals we can’t actually afford. The strategy to copy prestigious individuals only needs to be right on average to have survived this long. Which means it can still be wrong in plenty of specific cases.

Does Prestige + Signaling Explain Ineffective Institutions?

I suspect that this combination of signaling + prestigious copying explains the unusual persistence of many of the broken features of our modern institutions. Heathcare, education, politics, religion and more often have obvious flaws where there are clear fixes available. Yet, they don’t get changed because their signaling functions often override their actual usefulness.

Put in other words, schools often don’t fully reform because the reforms that would make them better for learning make them worse at giving credentials. Hospitals focus on expensive interventions rather than cheap preventions because showing you care matters more than promoting overall health. Politics centers around drama instead of policy because drama allows you to show people which team you’re on better than abstract policy discussions.

The lesson of signaling is that when the big things in the world around you look broken, it’s often because you don’t understand the function they’re really trying to serve.

In a normal environment, competition might eliminate these inefficiencies. A competing institution, that is better formatted to how people actually learn, might defeat reigning universities in an open contest.

Except that because we copy prestigious individuals, institutions that gain prestige themselves may persist much longer than they should. Universities, healthcare systems or even modes of governance can become sclerotic but survive because their accumulated prestige means that people emulate them unconsciously and thus they can maintain their monopoly.

When Should You Avoid Emulating Successful People?

As a practical matter, the prestigious copying works well. If it didn’t, you probably wouldn’t be reading this now. In fact, you probably wouldn’t be reading anything, instead just eating some raw meat from an animal you had to kill with your bare hands.

However, with the existence of signaling, it can also backfire when you copy countersignals which hurt your success, but which successful people do to show that they can.

Deciding which are countersignals and which are the genuine causes of success isn’t easy. After all, if fully understanding the reason behind a successful behavior were easy, we would have evolved that, instead of blind copying. We haven’t because often saying what makes something work is a lot harder to say than simply noticing that it does work.

There are cases, I think, that are obvious enough that they probably are worth avoiding (or at least being skeptical of) despite the fact that successful people do them. Some examples:

- Wasteful spending of money and time. I think most people will accept that owning a Ferrari doesn’t make you rich. But how many of us fetishize the weird investment habits of people who have unlimited money to waste?

- Excessive pickiness and avoiding grubby work. Some successful people boast about turning down opportunities or avoid doing some work that’s hard, but probably necessary when you’re just getting started (like pitching your work instead of just passively receiving opportunities). Some of this is simply a consequence of a different life situation, but I suspect some of it also functions to say, “I’m important enough that I don’t need to do X anymore.”

- Weird rituals that are probably useless. Any success advice you read that starts with what person X has for breakfast in the morning is probably bogus. Similarly, I think it’s no surprise that weird health trends like anti-vax, detox crazes and strange supplements are mostly applied by those who are already healthy and rich. They have the money and body to tolerate those treatments.

Another good way to spot for signaling is to notice when people say X a lot more than they actually do X. If the proportion of saying-to-doing is high, X is probably more of a signal than an actually useful task. In contrast, if the ratio is the opposite: most people do it, few admit it, then it’s a kind of anti-signal, something that is very effective despite the fact that people don’t want to admit to doing it.

Although I think there’s probably benefits to applying some skepticism when copying prestigious people’s personal habits, the mysteriousness of why many culturally adapted traits actually work should also oppose going to the opposite extreme: dismissing everything unless you know exactly why it works.

The best answers are usually somewhere in-between. A mixture of wide-eyed (as opposed to blind) copying, and careful analysis to try to tease out the places where people’s words and deeds conflict to see what really matters.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.