Some ideas are so powerful and general that once you learn them deeply you start to see them everywhere. Efficient markets is one of those ideas.

Unfortunately, efficient markets is also an idea that gets a lot of hate. The reason is that the simple logic of efficient markets often leads to conclusions people would rather not accept.

My point of this article isn’t going to try to persuade you that all markets are efficient, but to help you understand the idea. Even if it doesn’t apply because one of the fundamental assumptions is violated, efficient markets still provides a powerful “default” way of viewing complicated human systems that would otherwise be quite confusing.

Let’s dive in…

What are Efficient Markets?

Efficiency is a concept from economics that simply means you can’t make anybody better off without making somebody else worse off.

Consider a world in which Bob has $1,000,000 and Julie has $1. This could be “efficient” because in order to give Julie more money, Bob has to have less. Thus, don’t think of “efficient” as being “fair” but simply that there aren’t any ways to change things to make everyone better without making at least one person worse off.

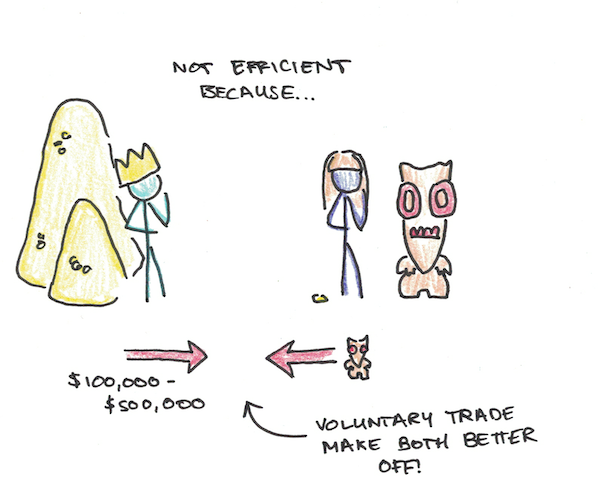

Now, however, imagine that Bob has $1,000,000 and Julie has a rare artifact. Bob would be willing to spend up to $500,000 to have the artifact. Above that, and he’d rather have the money. Julie would be willing to sell it for as little as $100,000. Below that, and she’d rather keep it.

This state, of Bob having money and Julie having the artifact, is no longer efficient. Why? Because we could simply move anywhere from $100,000 – $500,000 from Bob to Julie and the artifact from Julie to Bob and they would both be better off for it.

This is the power of markets and voluntary trades. It allows both people to be better off than they would be if they couldn’t exchange things.

Supply and Demand

The world has more than two people in it, however. As a result, when we imagine efficient markets we’re usually considering lots of people selling something (say televisions) and lots of people buying them (say television viewers).

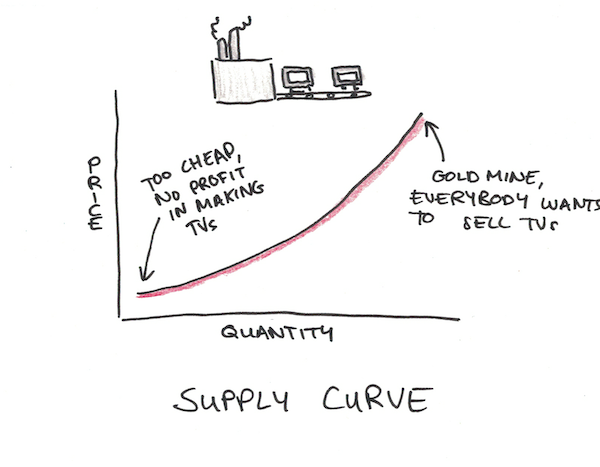

People who make televisions would sell more of them if they could get a higher price. If people would buy each television for a million dollars, television manufacturers would want to make a ton of televisions, after all, they cost a lot less than a million dollars to make. New people would start television companies to keep up with the gold rush.

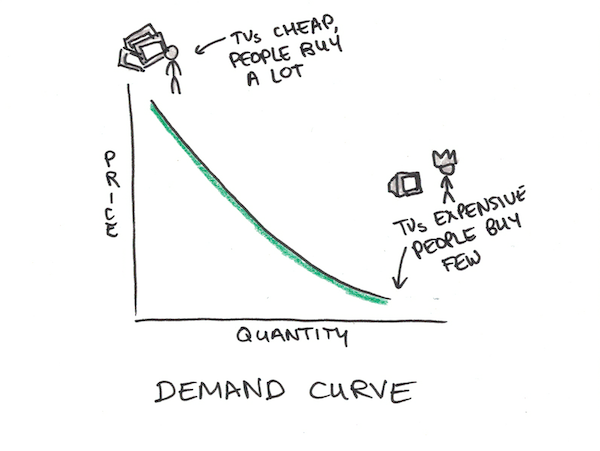

Similarly, people would buy more televisions if they cost $1. You might have four or five in your house. You might throw your old one out and buy a new one every six months. You might give them as gifts when you visit your friends or use them as serving plates. Cheaper prices cause people to buy more.

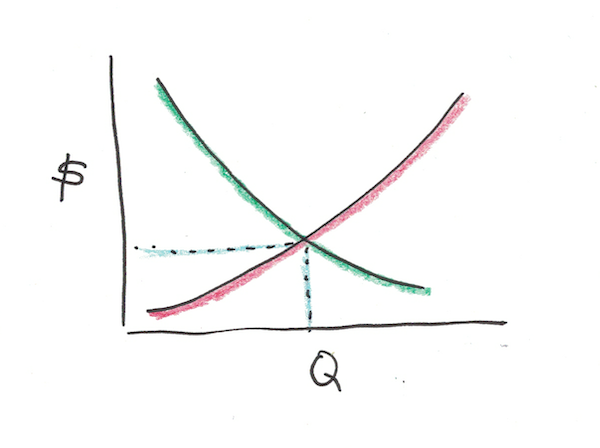

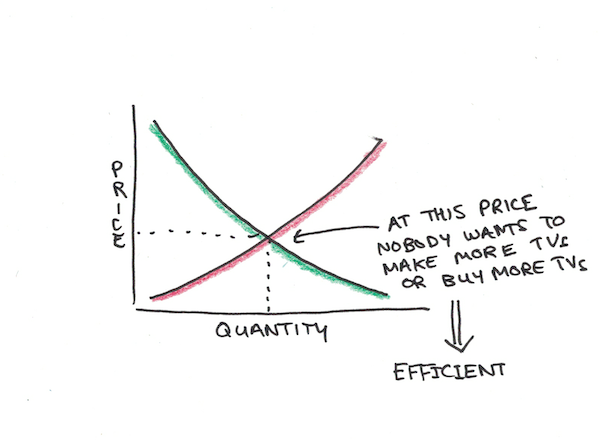

These two phenomena are known as supply and demand curves. Supply curves tend to curve up, as prices rise, people want to sell more. Demand curves tend to curve down, as prices rise, people want to buy less.

Efficient markets say that the actual price of televisions will be when the amount people want to buy equals the amount people want to sell. At this point, the arrangement is “efficient” because you can’t make anyone better off with further trades.

If people made and sold more televisions, they’d have to sell them to people who want them for less than the amount of money television makers are willing to accept.

Lessons of Efficient Markets

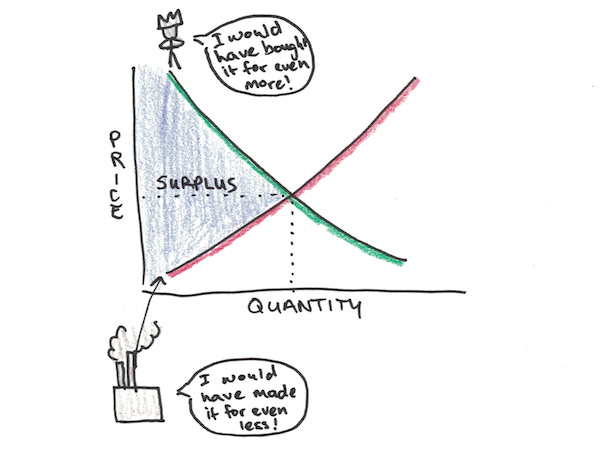

The first lesson of efficient markets is that markets make almost everybody better off. Remember those sloping curves of who wants to sell and who wants to buy?

Like our example with Bob and Julie, Bob is willing to pay much more for the artifact than Julie is willing to sell it. So when the artifact changes hands, the difference between them is what’s known as surplus. Surplus indicates the total amount that people are “better off” by trading than they were before.

It’s possible that Bob is a shrewd negotiator and convinces Julie to sell her artifact for only $1 above her minimum selling price. In which case he captures $399,999 of “consumer surplus.” Julie, is still better off, but only by a measly $1 of “producer surplus.”

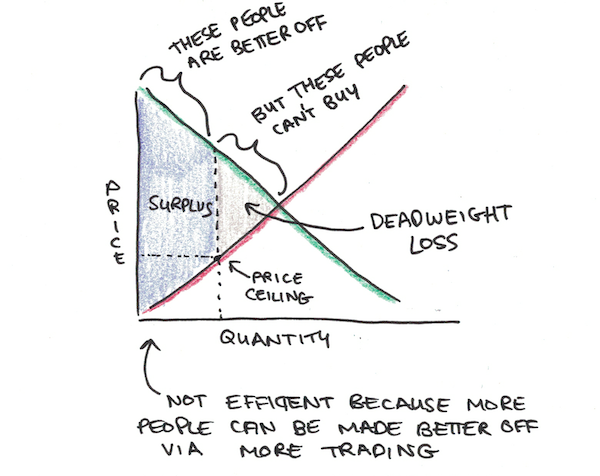

Suppose now, that someone came in and forbid anyone from selling below or above a certain price. If this price was above the efficient price, now some people who would like to sell aren’t allowed to sell to some who would like to buy. The arrangement is no longer efficient and we have what economists call deadweight loss.

Monopolies (where one seller sells to many buyers) or monopsonies (where one buyer buys from many sellers) can also create deadweight losses. The price a monopolist wants to charge is usually higher than the competitive price, and so there exist people who would like to buy, but can’t. In these cases, forcing the monopolist to charge the “competitive” price can increase surplus, even if it makes the monopolist worse off.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

With the basics of supply and demand understood, now we can look at an extension of this idea, applied to the stock market.

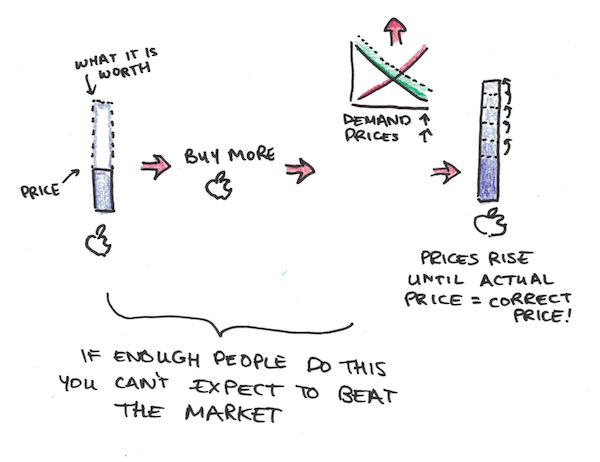

Suppose I know, with certainty, that Apple’s stock is going to go up. This means that when I buy it now, wait a little bit, and sell it later, I will make a lot more money than I would buying other stocks.

As a result, I go out and buy as much Apple stock as I can, since I can make guaranteed extraordinary profit. The result of this, however, is that the quantity demanded increases, and so the price rises. It will keep rising until the price of Apple’s stock no longer makes it a great deal. If I hold it and sell it later, I won’t make more money than I would buying other stocks, so I stop.

What this dynamic suggests is that prices are self-correcting. If I have secret information that makes something more valuable than its price suggests, I will buy more until the price reflects the correct price.

This is true even if my guess at Apple’s stock price rise is only probabilistically correct. Just like how you can make money from a blackjack table by counting cards, it’s not that each hand will win, but over time you can make money since each bet is slightly weighted in your favor.

Similarly, prices will adjust to the “correct” price, even if people only have partial, probabilistic information about what will happen in the future.

The efficient market hypothesis states that any information about the value of something will automatically adjust the price until the price matches what people think it is worth.

Applications of Efficient Markets

First let’s look at the simple case of efficient markets, without the extension to stock markets and information.

One of the lessons of this case is that price caps and floors are really bad. In a normal market with sufficient competition, setting a price floor makes people worse off.

It’s easy to see this with televisions. If I force people to sell televisions at $100, but there are producers who would like to sell it for $90 and consumers would would buy it for $95, there are trades that could make everyone better off that nobody is taking.

Where this gets controversial is when this logic is applied to things other than televisions. Minimum wages are price floors. This makes those who get jobs better off, but it means there are those who would work for less who can’t get jobs.

The main argument against “efficient” markets here is when we have a monopsony. If there is only one company hiring and many employees, the company may pick a price where people still want to work (because they need to eat) but far closer to their minimum selling point rather than the companies maximum salary they can offer. Like Bob being the shrewd negotiator, employees may be left off with less.

My point isn’t to support or criticize minimum wages here, but simply to point out that most people automatically think of them as good with no downside. Efficient markets suggest that, at least in some cases, they may actually be bad. Whether that’s true in the real world, is a more complicated matter, but the mental model is still useful.

You can similarly apply this idea to restrictions on price gouging, rent control, export quotas and much, much more.

Applications of Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

The efficient market hypothesis takes this idea and argues that it implies that asset prices which are frequently bought and sold will tend towards having the “correct” price.

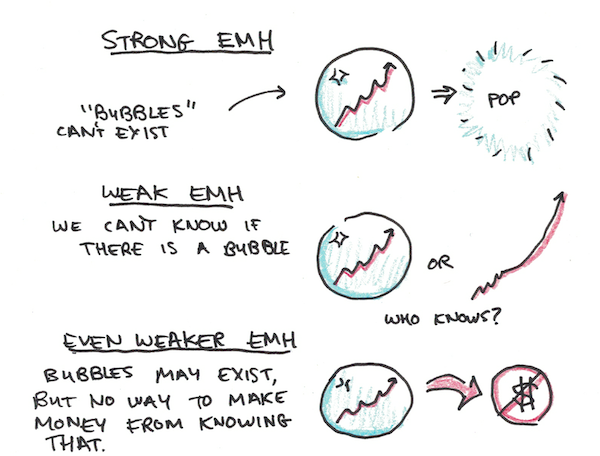

There tends to be two forms of this hypothesis a “weak” form and a “strong” form.

The strong EMH says that since information corrects prices, bubbles and panics are impossible. If it looks like there’s a stock market bubble, that’s just an illusion because if prices were really overvalued, it would retreat to the correct price. It hasn’t, so prices are correct.

The weak EMH says that prices don’t need to be correct, only that there can’t exist any reliable information to say that they’re wrong. In this case, you could imagine that there’s a new technology. It has a 50% chance of completely revolutionizing the world and a 50% chance of being a total bust. Nobody knows which.

It’s possible that stocks for this company might soar, because there’s a 50% chance that they will become huge. Except, in this version of reality, the technology turns out to be a bust. The prices then crash. This isn’t a violation of the weak EMH, simply because nobody knew which way it would turn out.

Similarly, there’s an even weaker EMH, which argues that prices may be “wrong” but they’re not exploitably wrong. Consider the housing market for a booming city. If half of the people think the prices are going to skyrocket and the other half think they are going to crash, but you can only buy houses, never short them, then those who think it is going to crash can’t “vote” in the market unless they already own a house. This can create a lopsided bet where the price isn’t correct, but there’s still no way to abuse that information to make money.

I’m not sure this weakest version can still be said to be the EMH, but it’s still worth considering.

One straightforward implication of the EMH (in all its strengths) is that it suggests that you can’t beat the market under normal circumstances. You may do so, out of luck, or by taking on extra risk, but you can’t do so consistently, unless you possess information other people don’t have (i.e. insider trading).

Side note: Some variants of the EMH argue that markets even incorporate this “inside” information, so even insiders can’t exploit the market consistently.

EMH also can serve as an approximate guide to things other than stock markets.

The remunerations for a career (pay, prestige, flexibility, fun) must roughly equal its costs (school, skill, difficulty) since otherwise people would gravitate towards that career, competing down the benefits. See an article I wrote applying the mental model of efficient markets to career choices.

Applying Efficient Markets

Each of these implications of efficient markets depends on a lot of assumptions. If the assumptions don’t hold, the mental model may not hold either.

Deeply learning a mental model involves both spotting it as an analogy in the world, as well as recognizing when the assumptions it requires may not be met. It’s totally fine, for instance, to come away from this article realizing that actual human markets don’t approach the efficient ideal. There may be transaction costs, search costs, monopolies or monopsonies, for instance.

Yet, good mental models are still a powerful way to view the world, since when the assumptions do at least approximately hold, they can suggest interpretations that might not be obvious otherwise (like that consistently predicting the stock market to get superior returns should be nearly impossible to do).

Side note: I’m considering making a series, exploring mental models like this one. Do you have any ideas you’d like me to share? To those with economics training, are there any implications about efficient markets I missed? Feel free to continue the discussion in the comments!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.