Biases distort our perception of reality.

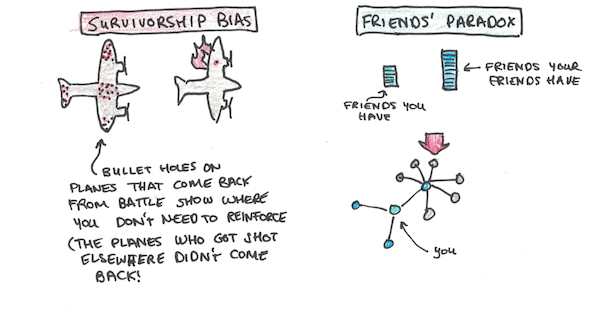

Consider survivorship bias. This is the fact that when viewing a group, you often only have the ability to look at the success stories, not the losers. As a result, you may be deceived that certain traits matter because they show up in all successes (even if they also show up in a lot of the failures too).

Or consider the friends’ paradox. This occurs because your assessment of what is common amongst your peers is based on what your friends do. However some people have more friends than others, which means that when you take an average of your friends, the more extroverted people get counted more. This leads to perceptions of drinking and promiscuity being higher than the actual average, due to a distortion in who you look at.

These biases are real, but today I’d like to look at a different one: achievement bias.

Achievement Bias: You Only Hear About Those Obsessed with Success

Consider two friends. One decides that becoming a successful scientist is the most important goal in life, works non-stop and eventually becomes a Nobel-prize winner. The other decides that a nice, comfortable family life matters more and earns a respectable income, but never becomes world famous.

Question: whose biography are you going to read?

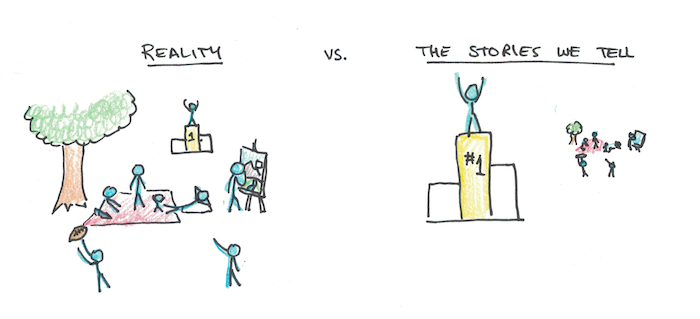

The peril of achievement bias is that achievement crowds out other values when considering what makes a good life, as seen in the lives of others. If we assume that valuing achievement is at least correlated with achieving it, the result is that those who achieve great success disproportionately value achievement compared to the average.

There are two major dangers to achievement bias.

The first is that it makes the pursuit of success look more common than it really is. Since you only see and read from the minority of high-achievers, it can create the impression that most people also value success to the same degree.

The second danger is that those who don’t value achievement at all are silent. In other words, if you value something that is incompatible with success, your story is unsung and nobody will hear about it. This can mean that the virtues of a life not devoted to striving are missing.

Why Even Famous Non-Achievers Over-Achieve

The real funny part of achievement bias comes when it deals with the “success” of speakers, thinkers and philosophers who pride themselves on virtues other than achievement.

Nearly every famous speaker and writer on spirituality, whose work argues in favor of well-being over material success, is nonetheless famous and successful. Which means that those people are either accidentally successful, or they are at least selectively hypocritical to their own message—focusing on massive outreach, book deals, speaking tours and seminars over inner peace.

This isn’t to rebuke those people. In some ways, I laud them for having the ability to tell a much-needed message despite the fact that achieving such a message often times counters to the philosophy they try to espouse.

My point isn’t to criticize the hypocrisy but point out that even with mild hypocrisy the promotion of achievement as a virtue is probably excessive.

I’m just as wrapped up in this as anyone else. I also value achievement very highly. That valuing has put work central to my life in times when it wouldn’t have been for other people. That same prioritization also means you’re reading my words today. Thus, the advice you receive from me is, at least in part, a factor of my personality and values rather than a truly objective assessment of what is best for you.

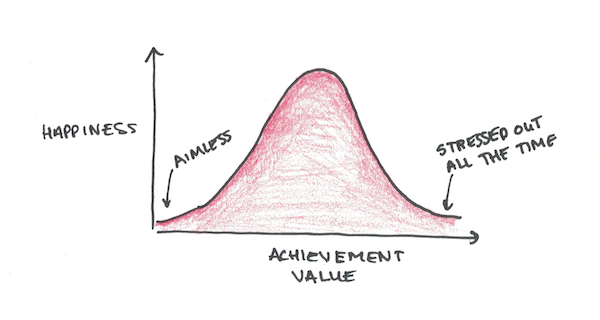

Why Might an Overemphasis on Achievement Be Bad?

Life is full of trade-offs. You can sleep in or wake up early to work. Spend money on that fancy trip or put those dollars away for retirement. Stick to your diet, or enjoy that pizza.

Achievement, like all other good things in life, must also trade-off against other values at the extremes. Albert Einstein was a great scientist, but he also had a lousy marriage. While I think the world is better off from his dedication to science, I’m not sure his wife would have agreed.

Prioritizing achievement itself is a valid choice. The problem with achievement bias is that if you want to learn and study from people who aren’t in your immediate vicinity, it’s difficult to learn from anyone who didn’t prioritize achievement in this way.

Is there a hidden subset of the population that are happy and unremarkable? Perhaps these exemplars are worth learning from more than just the people who made millions by obsessing themselves with success.

How Do You Counteract Achievement Bias?

Achievement bias is like all other cognitive biases, easy to point out, very difficult to overcome.

For every pundit that heckles, “Survivorship bias!” when someone talks about the morning routines of famous CEOs, I want to yell back, “But what are people supposed to do?” The fact is that even if there is a survivorship bias, gathering up all the people who weren’t successful and statistically controlling for their results is an enormous project that would require teams of trained researchers. Not something an ordinary person can actively counteract.

Achievement bias is similar, because it’s harder to argue the opposite. Writing is a skill. Like most skills it takes years of work to get good at, the kind of thing that someone who values achievement might do. If you don’t value achievement, and don’t get really good at writing, you probably won’t be very articulate arguing in favor of non-achievement as a virtue.

I think this bias probably means we should consider non-achievers words more carefully, especially since those voices are rarer. It also means we ought to talk to more everyday people and not merely look up to the most famous and successful for all worldly wisdom.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.