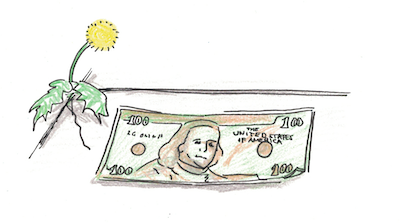

There’s an old joke about an economist walking down the street when he steps on a $100 bill lying on the ground. He spots it, but decides to walk right on by.

“After all,” he chuckles to himself, “if that had really been a $100 bill, someone else would have picked it up already!”

It’s easy to make fun of this way of thinking, but maybe the economist being lampooned here is actually right. When’s the last time you saw a lot of cash lying on the ground? In the real world, people don’t let $100 bills linger on the sidewalk.

Finding lost money is nice, but otherwise trivial. Instead, let’s consider the more abstract (and important) version of this problem, namely: how many opportunities are lying under your feet that you might be ignoring?

The implications of this are vast. If a business idea is so great, why isn’t anyone else doing it? If a scientific discovery is ripe to be found, why isn’t there a team of academics already probing for the answer? If something is broken, why isn’t anyone trying to fix it?

Ultimately, it’s not just $100 bills lying on the ground, but billion dollar companies and life-saving technologies that we may be stepping over, so I think it makes sense to think deeply about this question.

“Someone’s Already Doing That”

I once took a class called Technology in Entrepreneurship. The instructor had just recently finished his PhD, and this was a relatively new class with an unproven format. One of the assignments of the class was to come up with a “new idea” for a technology, for which our grades were based on the business viability.

I mention that it was a new class because this idea for an assignment didn’t work at all!

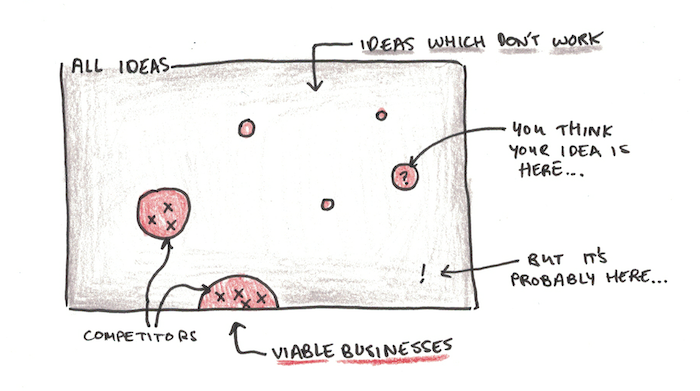

Virtually nobody in the class could come up with a genuinely “new” idea. Every time we, as plucky business school students, came up with a new concept that had actual market viability, it turns out a quick search revealed several companies who were already doing that exact thing.

This is part of the reason I chuckle when people want a confidentiality agreement before sharing their business idea. If the idea is any good, there are probably three or four companies already doing mostly the same thing.

As an entrepreneur, though, this isn’t a major problem. Competition is actually good because it demonstrates that other people think the market is viable. It’s when nobody is doing your business idea that you really need to get worried. Ideas without competition are usually bad.

The other lesson to draw from this experience is that, if you want new innovations, don’t ask undergrad business students to come up with them.

Leaps in innovation tend to come from people who are situated at the cutting edge of a field. They can see what might be possible a bit before other people. To use our $100 bill analogy, it’s like you find a $100 bill lying on the ground, but instead of being on the street, it’s in a private garden that only a few people can access. Suddenly the possibility that nobody else has discovered it seems a lot more likely.

But What About the Bicycle?

This line of reasoning seems to weigh in favor of innovation being hard. Most good ideas for companies are already being pursued. This isn’t a death sentence for a would-be entrepreneur, but it does put a limit on how much totally unexpected innovation should be possible.

But, then again, what about the bicycle?

Bicycles were not invented until the late 1800s. But why? All of the component technologies existed long before then. Requiring only human power to greatly increase speed and mobility, a bicycle would have been very useful in a world that only had horses and wagons. And yet, nobody seems to have thought of inventing one.

In this fascinating article, Jason Crawford dives deep into offering an explanation, but importantly, he rejects some common explanations:

- “Roads weren’t good enough!” But bicycles don’t need perfectly smooth roads, and they became popular largely before good roads.

- “Horses were everywhere!” True. But bicycles don’t need food and space, so from a transportation perspective they surely would have had advantages over horses (just as they do today).

Instead, Crawford argues that a major factor was simply that inventing the bicycle is hard. It’s difficult to get all of the design decisions right that will lead to not only a successful vehicle, but a commercially viable product. As a result, bicycles probably didn’t get invented earlier because nobody thought of them!

The bicycle example suggests an opposite view to our earlier example of all good ideas being taken. The bicycle is very clearly a good idea, but for centuries, nobody had thought of it.

So Which is It? Is Innovation Easy or Hard?

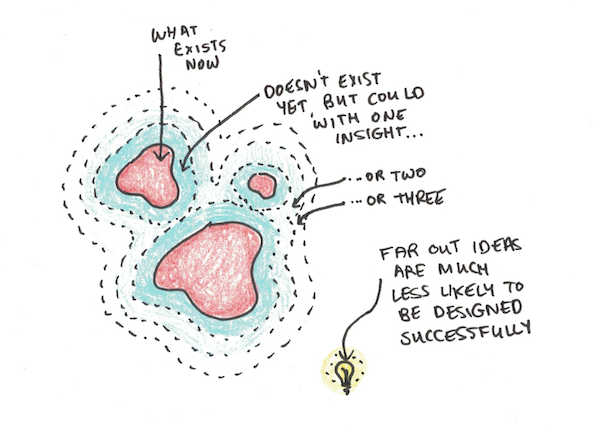

My own view of the situation is this: the potential for innovation is vast, but people can’t see more than one or two steps removed from what currently exists.

It’s easy to blame this simply on our own conformity and short-sightedness. But I don’t think the bicycle story really shows that. Early designs for bicycle-like things did exist.

Rather the difficulty was that, in order for the bicycle to really work, you need to get several independent factors right simultaneously:

- Single rider. The first designs for a human-powered vehicle were for multi-person carriages, not individual riders.

- Two-wheeled design. It’s not obvious that a two-wheeled vehicle would be stable, or indeed preferable to clunkier designs.

- Pedals. The first proto-bicycle, Karl von Drais’s Laufmaschine (running machine), did have the first two elements, but it lacked pedals. To make it move you had to run while riding it. Useful for coasting, but far from the usefulness of a modern bicycle.

- Gears. Even when pedals did arrive, they were connected directly to the front wheel. This is like pedaling on a really low gear. To compensate, designers made front wheels bigger, but this also makes them harder to balance.

- Rubber tires. One early version had the nickname “boneshaker.” Comfort, it seems, was a later innovation.

What we can see here is that inventing the bicycle might have been possible, but it was far from obvious. Several discrete innovations are required to have useful bicycles, and more than one are required to make something beyond a simple prototype. Without an active market for the vehicles, invention and discovery were limited to hobbyists.

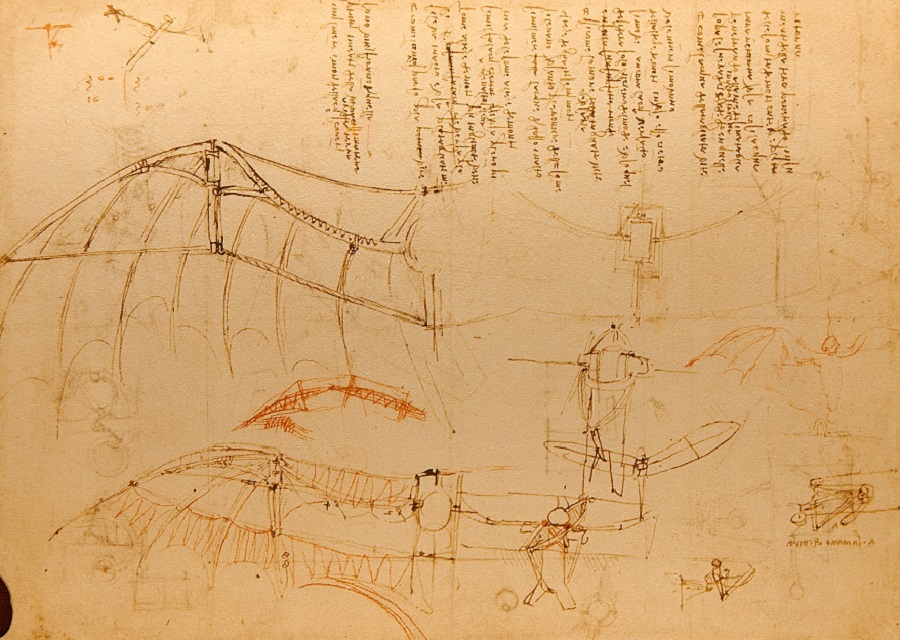

The more unproven design factors need to be incorporated for an invention to succeed, the more likely that you’ll fail to think of one of them. When this happens you get things like Leonardo da Vinci’s early designs for flying vehicles—innovative, to be sure, but hundreds of years ahead of a working prototype.

How Do You Find the $100 Bills Lying on Your Sidewalk?

While these examples have lessons for innovation at a societal scale, I think they also teach us important lessons about improving our own lives.

First, if you want to pick up $100 bills, go to the place you see people scrambling for them! If you want to choose a good career—pick the one people are currently getting good jobs in. If you want to start a new business—pick the one that has tons of needy customers. The place nobody is looking is usually empty because there’s nothing there.

Second, most improvements happen only one or two steps removed from what currently exists. Most “tech” companies are really just applying the model of software entrepreneurship to other industries. They are innovative, to be sure, but usually only require an insight that combines what has already been done before. This is how innovation typically happens–totally unexpected ideas requiring multiple insights typically fail.

Third, while the zone of viable short-term opportunities is rarely free from competition, the space of possible future innovations is large and unexplored. These opportunities are often invisible because they’re not ripe for discovery yet. However, new things will open up as we inch closer to them.

And finally, if you see a $100 bill just lying on the ground somewhere—be sure to pick it up!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.