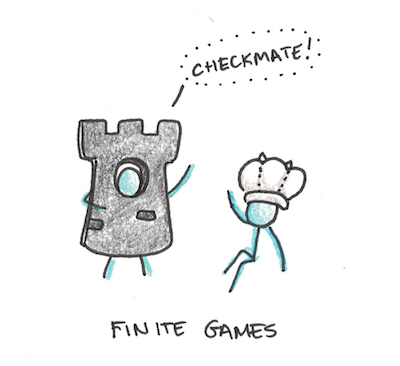

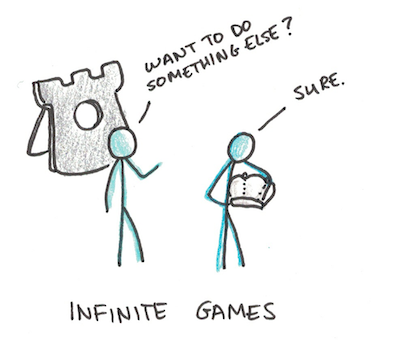

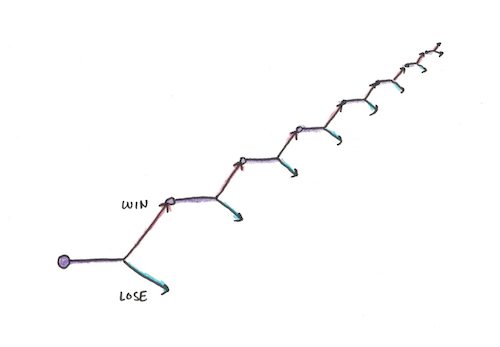

I like James Carse’s distinction between finite and infinite games. A finite game, like chess, is one that you play for awhile and when somebody wins, you stop. An infinite game, like life, is one where the goal is to be able to keep playing. To win at life means to keep living.

Most pursuits in life are infinite games. Business is an infinite game. There’s no point where you rank of all the companies, then decide for all-time which were the winners and losers. All “winning” means in business is the ability to keep playing the game.

Winning an infinite game is always a temporary state of affairs. Consider Jim Collins’ (in)famous book, Good to Great. Many of the companies he had singled out for higher performance failed to remain stellar in the years since. When you’re at the top of a hill, the only direction you can roll is down.

Rethinking Success

While all of us know that life is an infinite game, we often treat success as a process with final winners and losers. We liken it to sports, exams, battles or races—all finite games that end. This loose metaphor misses an important distinction: in life, much of success is simply being able to keep going.

I started writing when I was seventeen. I don’t think my early essays were particularly good, but if I possessed one thing it was stamina. I wrote five to ten essays a week for years, even though the possibility of making a career out of writing seemed distant at best.

In that time, I have met a lot of people who are more talented than I am. Very often they leapfrogged me and went on to greater acclaim. But, strangely, just as often, they would fizzle out. They stopped writing and went on to different things.

I can’t judge and say whether their choices were wise. Counterfactuals are really hard to evaluate. Maybe quitting was the right choice for them, I don’t know.

What I can say, however, is that, at least for me, success was largely a function of stamina. When people, starting out now, ask me about how likely it is that they can succeed at starting a business, building a popular blog or writing a book, my inclination is to ask, “How long can you try?”

Patience and Idleness

Of course, the kind of patience that eventually leads to success is not the same as waiting. Simply waiting does nothing.

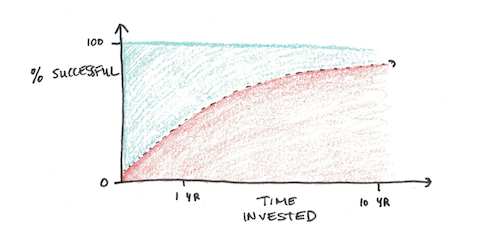

This is one idea that bothers me about popular notions of 10,000 hours or some other arbitrary time investment needed for success. The fact is that just investing time doesn’t do anything on its own. Even the research on deliberate practice, which inspired the 10,000 Hour Rule, doesn’t suggest that skill is simply a product of time investment. Quite the opposite, it asserts that most of our practice doesn’t count and the time we spend naively trying to improve is often wasted.

No, the kind of patience required for eventual success is an active, self-doubting kind of patience. It’s the kind that puts in enormous amounts of work, looks at that work and questions whether that was the right work to have put in, makes an adjustment and tries again.

Of course, it’s exactly this self-doubt and uncertainty which makes patience very hard. If you knew that success would come in exactly ten years if you just keep doing what you’re doing, then patience would be easy. Stamina is hard because, as with all infinite games, you don’t know how long you’ll be running for or even if you’re running in the right direction.

Build-Up and Breakthroughs

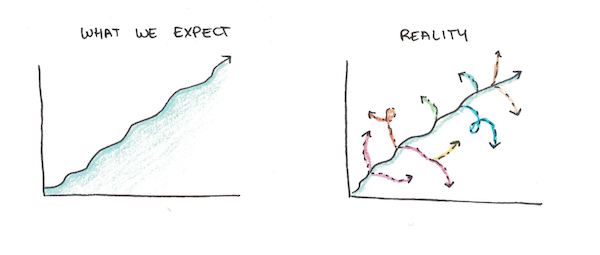

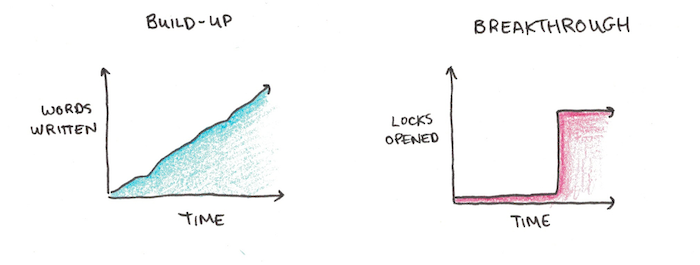

Part of the difficulty of stamina is that success tends to accrue in two different modes: build-up and breakthroughs.

Build-up is the steady accumulation of improvements. This is the stuff that’s easy to see and when patience is (relatively) easy. You see your business grow, month after month. Extrapolate that growth and eventually you’ll reach your destination. You see yourself gaining muscle at the gym, week after week. Eventually you’ll be strong.

Breakthroughs, on the other hand, are like puzzle solving. There’s a lot of effort, which does absolutely nothing, but every once in awhile there’s an insight that results in a discontinuous spurt. Think of trying to open a combination lock that you don’t know the code for—most of your attempts do nothing other than eliminate one of many possible sequences. Try the right code, however, and it opens in one pull.

In most pursuits, success is a mixture of breakthroughs and build-ups.

I remember distinctly a moment, now over a decade ago, when I was trying to grow my website. I could see that it was gaining traffic (build-up), but when I extrapolated the numbers I had so far, it was going to be decades before I was in a position where I could support myself from it.

What was missing from that extrapolation of future build-up, were the breakthroughs. Sudden improvements due to finally finding the right combination to unlock a new level of growth. When I eventually was able to support myself, it came from a single idea that finally worked. I created a monthly subscription program for study skills that proved to be popular enough to let me write full-time.

Stamina or Stubbornness?

It’s clear that, for any pursuit, an increase in your stamina will increase your success. Your health? Don’t let the oscillations in the scale dissuade you—keep exercising. Your business? Keep trying new things and stay solvent as long as possible. Your love life? Don’t let rejection or failure get you down, keep meeting new people and stay positive.

However, life rarely involves a single pursuit. We’re always, implicitly, trading one pursuit against another. Thus, even if those with greater stamina are more successful at one thing, their stubbornness may prevent them from picking a different pursuit where success comes easier.

Consider that, in many university departments, those getting PhDs have effectively zero chance of getting tenure. Stamina abounds, but many would have been happier keeping their intellectual interests a hobby and choosing a field that’s easier to build a career.

Stamina may increase the odds of success, but it also increases the costs of failure. Something you spent a few years at, decided you didn’t like and moved on is a life experience. Spending decades on a dead-end is a disaster. “Just be patient,” is not universally sound advice.

However, while dead-ends and pitfalls abound, it’s also clear that success in most pursuits requires stamina. Especially when success depends on breakthroughs, it’s often the case that one has to work hard for years on faith that everything will eventually pay off. This is difficult to do emotionally, even if the choice to persist is the correct one.

How Can You Increase Your Stamina?

Your stamina is, very often, by design. Lower your burn rate. Decrease your poverty threshold. Work on your pursuits sustainably, rather than in big bursts prone to burnout.

The key to long-distance running is pacing. If your running speed goes slightly higher than your body can effectively sustain, you’ll rapidly become too tired to go on. On the other hand, pick a speed just below that critical threshold and, with the right mindset, you can run for hours (maybe even days).

Similarly, a lot of stamina can be built into your striving directly. Simply set yourself up in a way so that sustaining effort for years is a viable option.

Other elements of stamina are mental. How can you cope with doubt? How can you be patient without becoming complacent? How can you prevent getting distracted by alternative pursuits that seem easier on the surface, but only because you haven’t realized the stamina they also require?

It’s tempting to reduce stamina down to a mantra. “Never give up,” or something like that.

Unfortunately, it’s precisely because giving up sometimes makes sense that stamina is hard. Dead-ends are everywhere and many efforts go nowhere. If you could guarantee that success would come eventually, then you’d only need to wait. But just waiting won’t get you there.

Therefore, I don’t think there are any universal slogans you can adopt that will simultaneously give you patience and release you from the emotional tension of struggling toward an uncertain goal.

The best that has worked for me, has been to ask myself whether I genuinely have better opportunities than this one. Usually the answer is no, so even if my current pursuits eventually fail, it still makes sense to continue down this path. However, even this advice only works if you correctly value your competing opportunities. If you chronically believe the grass is greener on the other side, you’ll keep hopping fences.

Another strategy I’ve found helpful is to focus on the process of pursuit itself, rather than the goal. If you can make that tolerable, even exciting, then whether you eventually reach the mountaintop you’re aiming at is less important. The people who run the farthest usually like running.

Most of all, I think it helps to recognize that life is an infinite game. If you get the opportunity to keep playing, you’ve already won.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.