How important should work be in your life? What kind of relationship should you have with your career? If you don’t feel like you have that, what should you do about it?

I’m usually against overthinking wants and likes. Consider cilantro. Some people (like me) think it’s delicious. Others think it tastes like soap. No amount of convincing can make cilantro-haters learn to love the herb. The taste may even be genetic, so liking cilantro may just be an immutable part of your make-up.

Career preferences are somewhat similar. For some, work not only provides them with a living, it is their life. For others, a job is what you have to get by—the background of your life, not main scene under the spotlight. Who am I to argue with either?

But, today, I want to try to ask how work matters and see how it fits into life. Not a prescription, but an exploration, to see how our relationship with our career comes to be and how we might improve it.

Why Care About Work?

The obvious reason to care about your career is that you need money to live. Survival ranks higher than lofty ambitions, so for most of us, a job is simply a necessity.

But many things are necessities without deriving much focused attention in life. Eating is also essential, but I don’t derive the meaning of my life from food. Indeed, it often seems like the people who focus most on their careers are those who need it the least. The lawyer who puts in eighty-hour weeks to make partner isn’t worried about rent money.

But if not survival, then at least comfort is a major aim of work. Even if you could survive, strictly speaking, on a smaller income, it would often make life more difficult. Similarly, most of us can imagine a bigger house, nicer things or an extra vacation as being worth the effort of getting a better job.

This perspective, that work is mostly about material survival and comfort, is one story we tell ourselves about work. It’s obviously true, but whether this is the main plotline or not depends on the person.

There are, however, different stories that you can tell yourself about your work.

Work as Respect

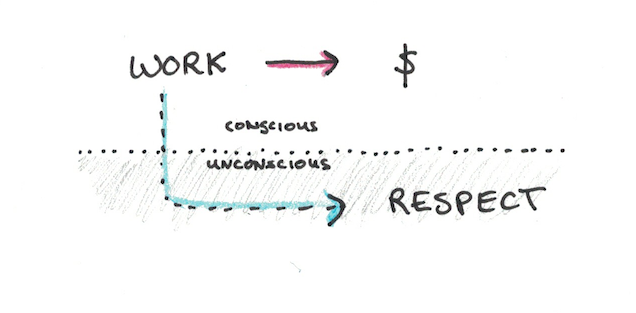

A different story, perhaps the one that a majority of people living in wealthier countries tell themselves, is that work is about respect. Your work decides some of your status in society, and doing well in your career is about mostly about amplifying the respect you receive.

There’s an element of self-deception here. Work being about survival (or even comfort) sounds better than trying to gain more status. Vanity and pride aren’t attractive traits, so many people mask their underlying desire for respect under different stories about their work.

Often, the only way you can unmask the true motivation is to see the choices people make in their work. When they turn down options with greater financial reward for those with greater status, you can see that clearly respect ranks higher than money in their unconscious minds.

I think this story, of work-as-respect, is a big part of the reason college education has exploded. While it is true that college does pay people more, this is only an average outcome. For those who barely get in, a few years of school only to end in dropping out is a financial disaster.

In contrast, many trades have a shortage of qualified people, despite offering very high salaries. College-educated jobs offer more prestige and so people are willing to sacrifice on material comfort to attain them. Anyone who pays $30,000 per year to study psychology rather than plumbing is, in a partial sense, saying that prestige matters more to them than material comfort.

Respect is an important, often unconscious drive, in our work, but it’s not the only story we tell.

Work as Play

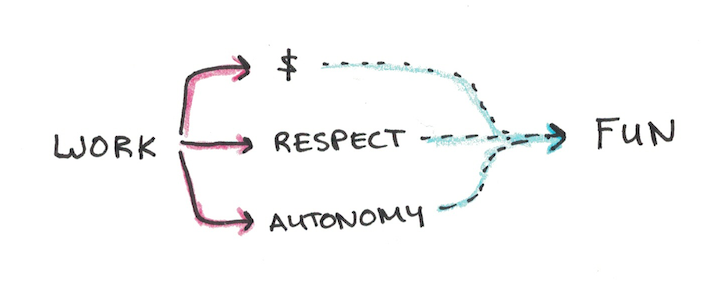

Normally we see work as something we have to do. But if it’s also something you enjoy doing, then you get both the financial rewards of work without having to sacrifice so many hours of your life on something that isn’t fun.

My own sense is that the story of work-as-play is important, but it tends to be overrated as an explanation for the work people pick. I tend to side with Cal Newport that most people don’t have pre-existing passions. Instead, people have the potential to like all kinds of work, as long as the conditions that surround work support it.

Indeed, many “fun” jobs are anything but. My friends who work in film, for instance, often complain about terrible hours, bosses or working conditions. Their passion comes with a price. In contrast, the friends who do “boring” jobs are often more satisfied since their work treats them better.

Still, play is an important story for work even if it’s probably downstream of other causes. Unsurprisingly, the jobs that are the most “fun” tend to be prestigious and high-paying. We’re quite psychologically flexible at finding rewarding things interesting.

Work as Purpose

In contrast to the intrinsic enjoyment one gets out of a job, your work is also a vehicle for creative self-expression and service. When you feel a job is purposeful, it not only provides a living, but a reason for being alive.

In many ways, this story is the exact opposite of the story of material survival. If your work is only for a paycheck, then it tends to be in the background of your life—friends, family or other personal goals often take center stage. In contrast, if your work story is one of purpose, it often steals the spotlight away from everything else.

What Creates the Story We Tell Ourselves About Work?

My sense is that there tend to be two forces that cause people to organize the meanings of their lives around certain stories: intrinsic and extrinsic.

The intrinsic forces are those, by nature of your personality or upbringing, tend to make you value some things more than others. As with cilantro, some of the feeling you assign to your career may be genetic. Others may be instilled from childhood. I’ve had friends for whom going to college was seen as uppity by their families, all the way to friends whose parents would disown them if they didn’t earn six-figures.

I think all of us have certain innate dispositions that lead us in some directions more than others. I don’t subscribe to the view that these dispositions are destinies, but I think it would also be a mistake to imagine ourselves as totally blank slates upon which any story can be written.

External forces also matter. I suspect that a lot of people alter the meanings of their lives in accordance with the kinds of experiences they face. If success in work comes easily, people are more willing to ascribe it importance in their self-conception. If it’s harder, centering one’s life around family, hobbies or spiritual pursuits might come more naturally.

However, I don’t think the stories we tell ourselves can be instantly reinterpretted in any way we like. Someone who values work in the extreme, and stumbles into professional failure, might persist for years in a state where the choice between overcoming adversity or telling themselves a new story remains unclear.

Should You Rewrite Your Story?

The meanings we ascribe to things tend to get fixed, the more we think of them that way. This stability is a good thing. Without it, life would become an incomprehensible mess.

However, rigidity of meaning can also get us stuck. If you’ve organized your entire identity around becoming a doctor, and you’ve failed to get into medical school for the third year in a row, what should you do?

When overly rigid meanings strain too much, they can sometimes snap. In 1837, in what was probably the most significant career failure of all time, Hong Xiuquan failed the imperial service examination for the third time. This lead to a nervous breakdown, deciding he was the brother of Jesus Christ, and kicking off the Taiping Rebellion which ended with a death toll of thirty million.

It’s healthier to have meanings somewhere between the two extremes. Stubborn enough, that one can persist through adversity. Flexible enough so that in the face of the obstruction of one path, you have the ability to choose another. Cultivating that correct degree of flexibility may be more important than the story you end up telling yourself.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.