As you get older, learning often feels harder than it used to. Why is that? What changes in the brain as we age that makes acquiring new information harder? Is there anything we can do to avoid our minds slowing down?

This is a topic I’ve been asked about a lot, but until recently one that I didn’t know much about. Aging wasn’t a topic I spent much time researching in my book, preferring to focus on principles of learning that are universal.

Recently, however, I decided to dig into some of the research on cognitive aging to see how our learning is impacted by getting older.

Learning Slows with Age

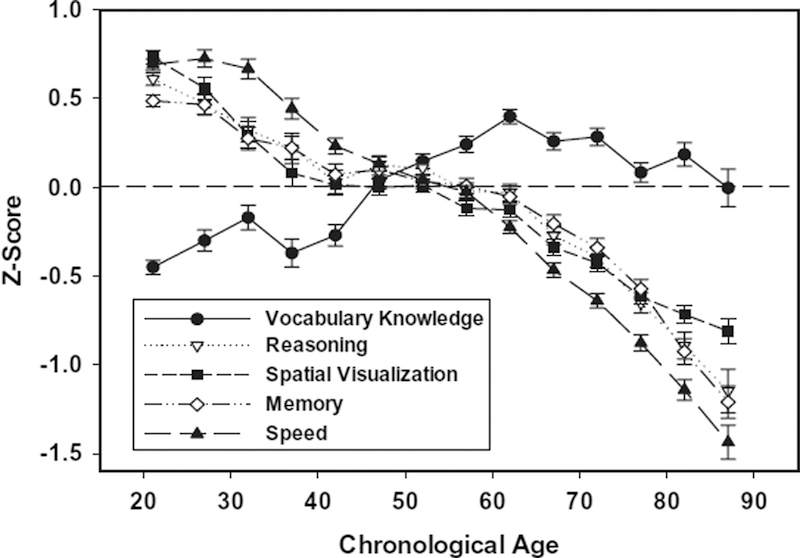

The first clear finding is that the feeling that one is getting slower mentally as we age is not an illusion—countless studies reinforce the fact that most aspects of mental processing get worse as we age:1

Interestingly, not all aspects of thinking get worse with age. Accumulated knowledge of the world increases until nearly the end of our lives, as you can see in the figure above with vocabulary size.

This is a trade-off between what researchers call fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. Even if our minds slow down as we get older, we accumulate more experience. We know more as we age, even if we’re slower at learning and processing new information. Wisdom increases even as wit declines.

What Gets Worse With Age?

There are different hypotheses about how our minds tend to get worse as we get older. A simple one is the idea that processing speed slows down as we age—neurons lose mylenation and so the signals that carry the currents of our thinking slow down.2

Other researchers disagree, arguing that aging impacts some brain areas more severely than others, resulting in specific deficits of cognition rather than an overall decline.

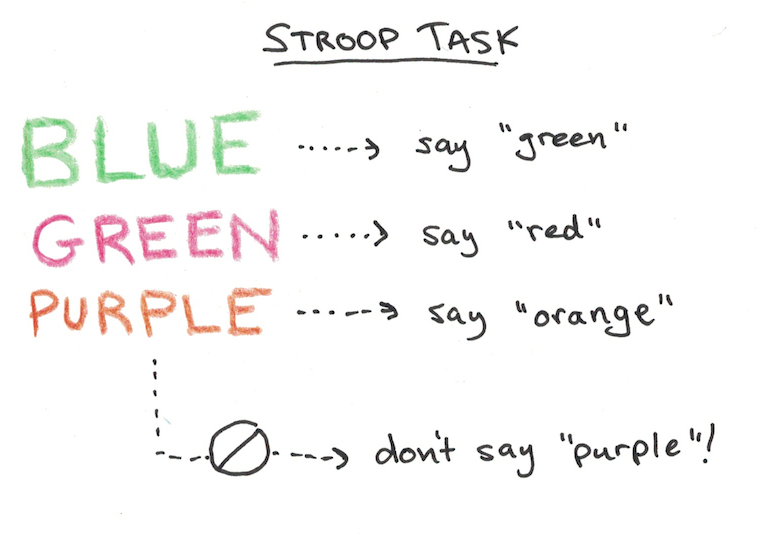

The frontal aging hypothesis argues that the frontal cortex is hit harder by aging.3 The frontal cortex is involved in many functions, but a key one is in asserting top-down executive control over our actions. This is often associated with the deliberate effort it takes to override habits or consciously keep intentions in mind when completing tasks.

Researchers Todd Braver and Robert West argue for a goal maintenance account of cognitive aging.4 Following the frontal aging hypothesis, this suggests that what is harder to do as you get older is to maintain and switch the goals associated with a task. This results in older individuals struggling more with Stroop tasks, where an automatic habit needs to be overridden by instructions:

Additionally, older individuals are hurt more by multitasking than younger people.5 This seems to be because multitasking requires switching the goals of the task at hand over a short period of time. Since older people have a harder time maintaining these, switching tasks frequently is particularly hard.

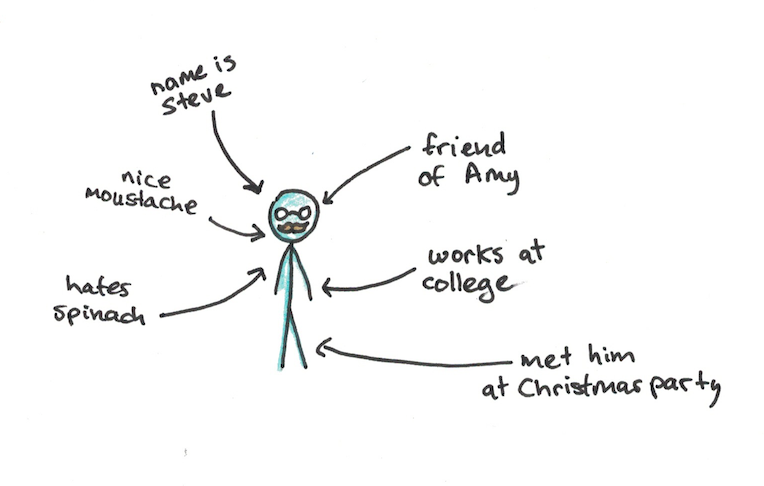

Another deficit observed in older individuals is difficulty with binding information that occurs in a combined context.6 Chunking is one of the most important parts of learning new information, so the fact that this becomes harder with age may explain why learning new things feels more difficult as we get older.

Difficulty binding information together to store in long-term memories also impacts our ability to remember our life events. Simple information is less impacted by aging, but as we get older we may start to forget the context in which something was learned.7 The person you walk by looks familiar, but you forget where you met him before.

The story isn’t all gloomy. In addition to crystallized knowledge, older people seem to be better at emotional regulation as well.8 Since managing emotions is an important part of success at many tasks, this suggests older people may be slower but surer at working on goals that have a bit of frustration baked in.

Do Different People Experience Decline Differently?

Do all people experience cognitive decline uniformly? Or do some people’s minds slip while others stay sharp much longer?

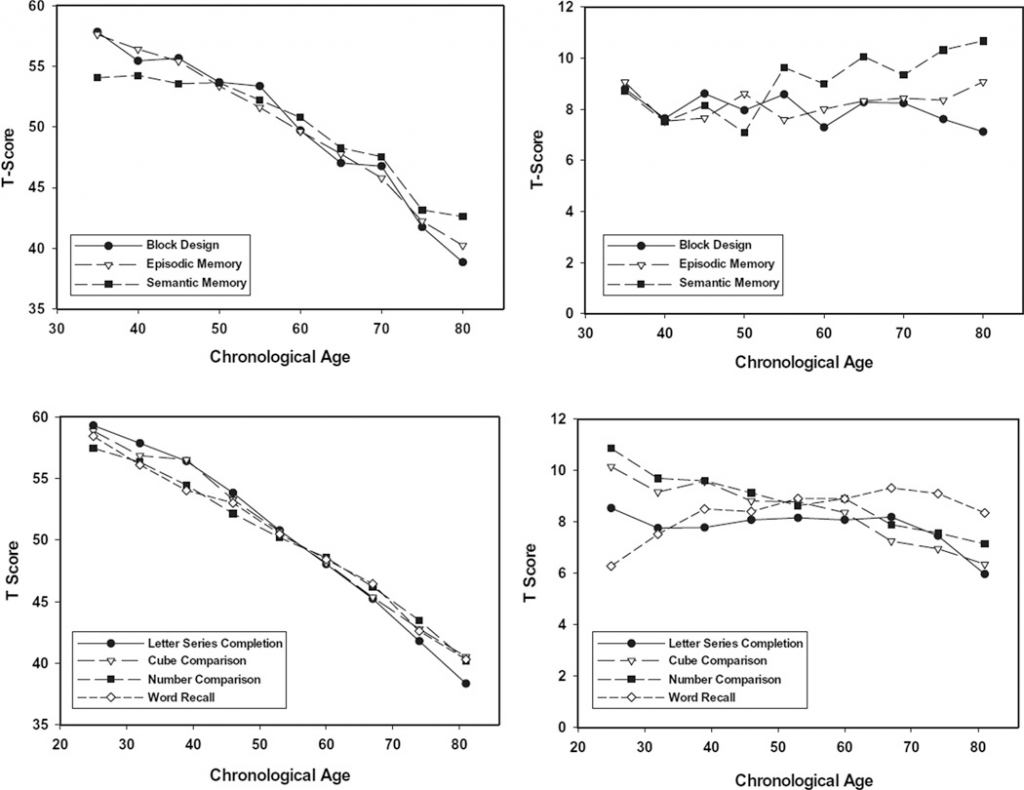

There seems to be a little conflict on this point in the research. One literature review I found argues in favor of cognitive decline being mostly linear as we age and not increasing in variance.9 This suggests that, absent illness, we’re all on roughly the same trajectory of cognitive slowdown.

This review, in contrast, seems to differ.10 The authors argue that variance increases with age, which goes with our normal intuition that some people seem to experience large declines in thinking with time while others fair much better. This seems to match up with other evidence that most factors associated with aging experience increasing variability over time.

Redundancy and Cognitive Decline

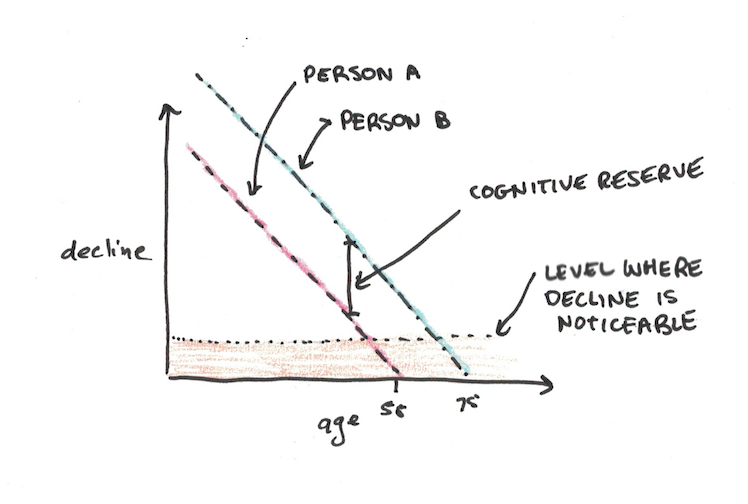

One reason for the observation that some people seem to age mostly with minds intact and others notice dramatic slowdowns may be that the brain has a lot of redundancy built in. On a physical level, brain volume may be declining, but that this may not create noticeable difficulties for some time.

Cognitive reserve is the concept used by researchers to note that many individuals who experience decline on physical measures may not have related mental decline owing to this robustness.11

One way you can see this is in fMRI scans which show that older individuals’ frontal cortices are more active than younger people’s on comparable tasks.12 Since frontal cortex decline is common in aging, what might be happening is that the brain is compensating for reduced efficiency by increasing activation.

Researchers note that education seems to have a protective effect on aging.13 This may be because accumulated knowledge from education contributes to cognitive reserve, so as our minds decline, those who learned more when they were younger are better able to cope. Of course, another explanation might also be that those with sharper minds were more likely to go to school, and that education has no causal effect.

How Can Older People Reduce the Impact of Cognitive Decline?

There is some evidence that some aspects of cognitive aging can be overcome with training.14 However, I wouldn’t hold my breath for a magic fix. Age impacts our minds just as it does our bodies. Just as there is no exercise regimen that will allow a septuagenarian to compete in the Olympics, I doubt there are universal remedies for our cognitive declines.

However, the situation doesn’t seem to be completely without hope either. There do seem to be some things you can do to help your mental functioning.

The first is preventing cognitive decline. Exercise and eat well when you’re younger. Learning more when you’re younger may minimize cognitive decline. Even if learning doesn’t prevent declines in fluid intelligence, it still enhances crystallized intelligence, giving you greater knowledge in your older years.15

The second is to strategically control your environment to minimize the specific difficulties associated with aging. In particular, you should:

- Avoid multitasking or environments with likely distractors. Since goal maintenance seems to be a central problem of aging, it means the older you are the more you benefit from an environment that allows your mind to focus on the problem at hand.

- Be more strategic with creating cues and reminders for important information. Proactive memory, where you set the intention to recall something later, given a specific prompt, is particularly affected by aging. This suggests engineering your environment to remind you of your goals and tasks is more important as one ages.

- Be more explicit in organizing what you want to learn. Binding pieces of information together to be recalled as a single chunk can happen both automatically and deliberately. Since binding is harder with age, it may make more sense to be deliberate about organizing information you want to learn.

A third idea relates to how you might allocate your learning throughout your entire lifetime. Since fluid intelligence and complex working memory peak in early adulthood, this suggests that time might be the best for learning skills where those are more important, such as mathematics.

In contrast, for subjects that require mostly accumulated knowledge and build off of past habits of thinking, age may be an asset rather than a liability. History and law, for instance, may benefit more from this accumulated wisdom and be more amenable to improvements later in life.

The idea that our minds change as we age, and thus change the relative ease of learning certain subjects shouldn’t be viewed fatalistically. Obviously, learning history when you’re fifteen or calculus when you’re fifty are both great. But understanding how age selectively impacts cognition can also help us to minimize the downsides of decline.

Footnotes

- Salthouse, Timothy A. “Selective review of cognitive aging.” Journal of the International neuropsychological Society 16, no. 5 (2010): 754-760.

- Salthouse, Timothy A. “The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition.” Psychological review 103, no. 3 (1996): 403.

- West, Robert. “In defense of the frontal lobe hypothesis of cognitive aging.” Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 6, no. 6 (2000): 727-729.

- Braver, Todd S., and Robert West. “Working memory, executive control, and aging.” In The handbook of aging and cognition, pp. 319-380. Psychology Press, 2011.

- Drag, Lauren L., and Linas A. Bieliauskas. “Contemporary review 2009: cognitive aging.” Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology 23, no. 2 (2010): 75-93.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mather, Mara, and Laura L. Carstensen. “Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory.” Trends in cognitive sciences 9, no. 10 (2005): 496-502.

- Salthouse, Timothy A. “Selective review of cognitive aging.” Journal of the International neuropsychological Society 16, no. 5 (2010): 754-760.

- Drag, Lauren L., and Linas A. Bieliauskas. “Contemporary review 2009: cognitive aging.” Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology 23, no. 2 (2010): 75-93.

- Stern, Yaakov. “Cognitive reserve.” Neuropsychologia 47, no. 10 (2009): 2015-2028.

- Davis, Simon W., Nancy A. Dennis, Sander M. Daselaar, Mathias S. Fleck, and Roberto Cabeza. “Que PASA? The posterior–anterior shift in aging.” Cerebral cortex 18, no. 5 (2008): 1201-1209.

- Habib, Reza, Lars Nyberg, and Lars-Göran Nilsson. “Cognitive and non-cognitive factors contributing to the longitudinal identification of successful older adults in the Betula study.” Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition 14, no. 3 (2007): 257-273.

- Erickson, Kirk I., Stanley J. Colcombe, Ruchika Wadhwa, Louis Bherer, Matthew S. Peterson, Paige E. Scalf, Jennifer S. Kim, Maritza Alvarado, and Arthur F. Kramer. “Training-induced functional activation changes in dual-task processing: an FMRI study.” Cerebral Cortex 17, no. 1 (2007): 192-204.

- Drag, Lauren L., and Linas A. Bieliauskas. “Contemporary review 2009: cognitive aging.” Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology 23, no. 2 (2010): 75-93.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.