Easily the best habit I’ve ever started was to use a productivity system. The idea is simple: organizing all the stuff you need to do (and how you’re going to do it) prevents a lot of internal struggle to get things done.

There’s a ton of systems out there. Some are elaborate, like Getting Things Done. Others are dead-simple, such as simply using a prioritized daily to-do list. Some require software. Many you can do with just pen and paper.

Being successful with a system long-term is hard. Here are just a few common problems:

- You have no idea which system to pick, or when you do pick something you constantly second-guess yourself that you’re “doing it right.”

- You get a burst of enthusiasm each time you try it, are productive for about two weeks, then you start to slack off and eventually abandon it.

- The system never seems to “fit right” for your life, yet you’re convinced the problem is that you don’t know how to work within it.

- The system you’ve chosen feels like a slowly constricting prison you’ve made for yourself, choking off your will to do meaningful work and turning you into a robot.

These problems can be avoided, but it takes a little thinking about what the point of having a system is and what it can and cannot do for you.

Why Use a System at All?

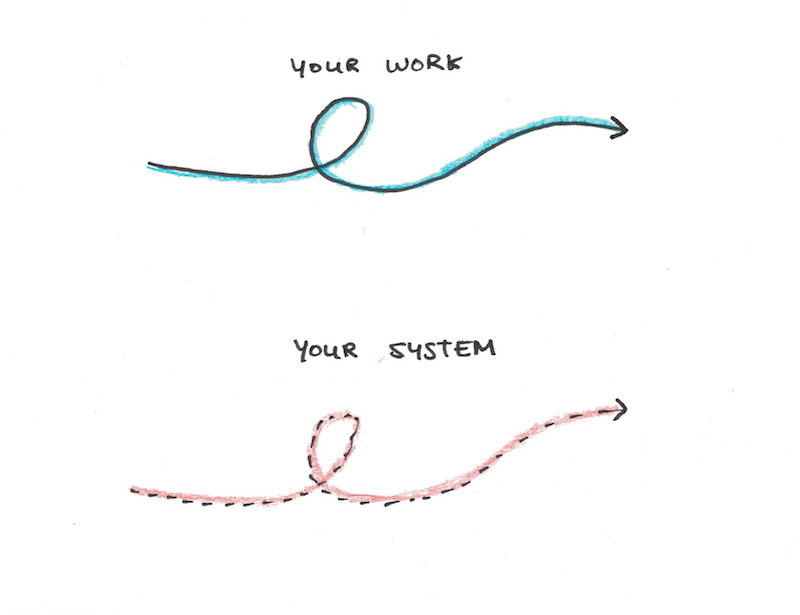

Ultimately, everybody has a system for productivity. There are really only three different kinds:

- The system of other people. You simply respond to the pressures put on you by colleagues, clients, bosses or family members. Big deadline tomorrow? I guess you’re working late on it.

- The system of feelings and moods. Feeling creative today? You might get a lot of work done. Does that thing that seemed interesting before now seem dull? I guess you’re not working on it. At its best, this can be fun and spontaneous. At its worst it can be soul-crushing to see you never make more than fleeting progress on anything with an ounce of frustration.

- A system of your own design. In this case, you create guidelines for yourself that structure your efforts. Moods and outside pressures still matter, but they’re no longer the only guiding factor about what to work on, how much and how often.

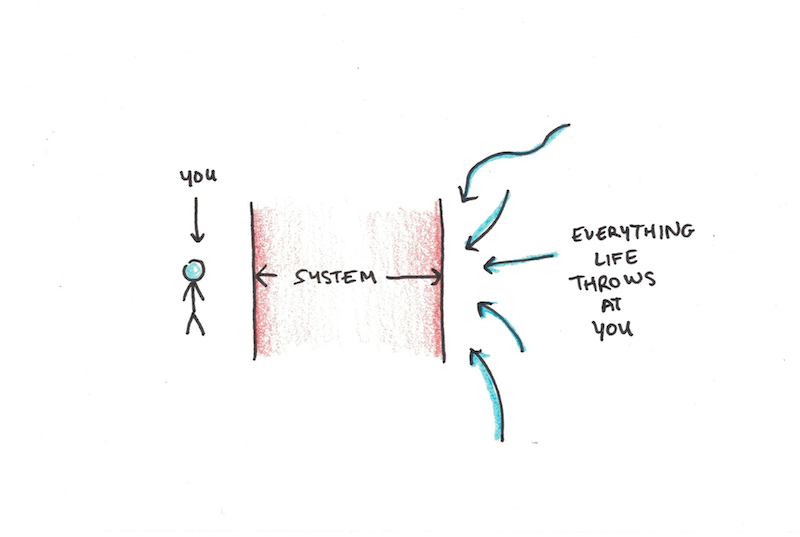

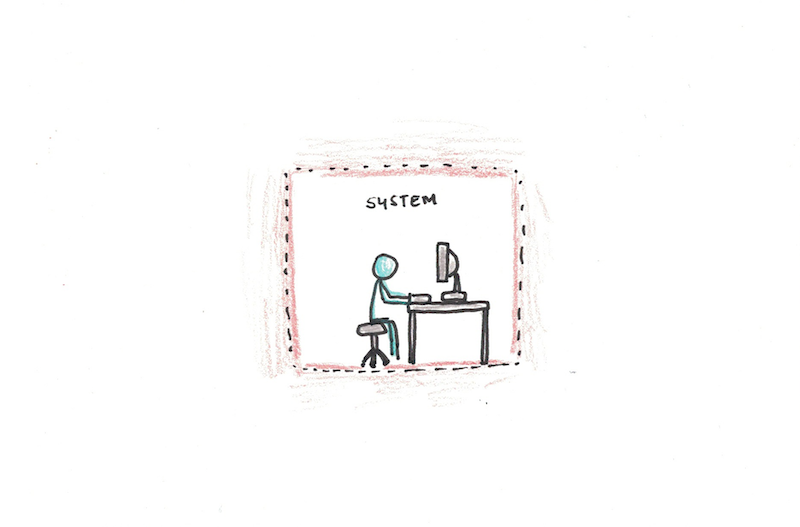

Building the habit of a productivity system is about self-consciously creating a buffer between you and temporary emotions or external agents. You still need to respond to deadlines and listen to your emotions, but those aren’t the only things you heed when planning your day.

If your system is going to be liberating rather than suffocating, however, you need to follow a few guidelines:

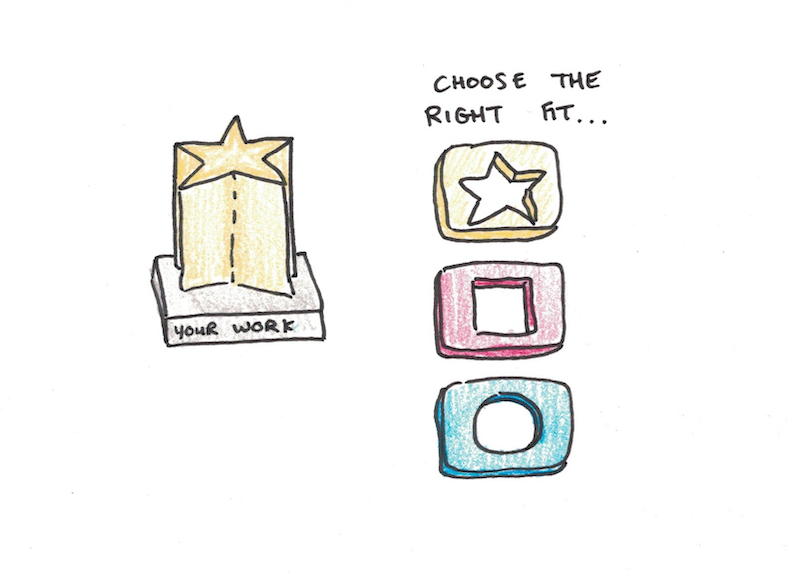

Rule #1 – Your system needs to fit your work (not the other way around).

Any system is designed using certain assumptions about your work. If those assumptions are wrong, the system may backfire.

Take Weekly/Daily Goals, the system I use most often. The idea is that you have two lists, a weekly to-do list and a daily to-do list. The latter is intended to be fixed—you decide what to work on that day and hold it constant, even if you finish early.

This system works well when you have a bunch of concrete tasks you need to finish that you might procrastinate on, but if you just sat down and did them all in a burst of focus you could probably get them done easily. The goal here is to use the potential reward of a workday finished early to get things done in an effective manner.

This system doesn’t work as well if your tasks are ambiguous and open-ended. It struggles more when your day is mostly meetings occurring at fixed times on your calendar. If your daily goals list just contains one task, “Work on X.” then it isn’t even functioning as a productivity system at all.

Therefore, before you get started with a system, it’s important to ask what the assumptions are that underpin it. What does your work need to look like for this to be effective?

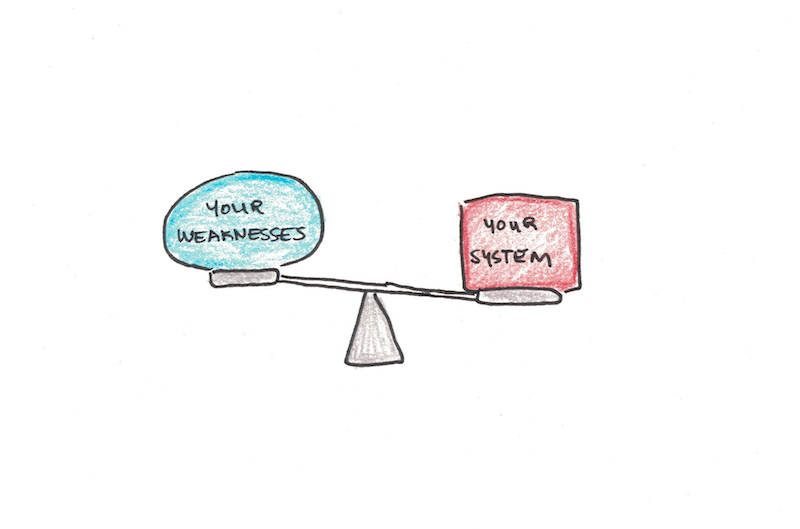

Rule #2 – The system should counterbalance your worst tendencies.

The guiding philosophy behind Getting Things Done is that, without writing down what needs doing, we’re liable to forget. Although the system aims at more than this, the key tendency it’s trying to counteract is simply forgetting what you need to do.

Fixed-schedule productivity counterbalances the tendency to constantly work overtime, having your office hours bleed into your home life. You’re answering emails at midnight, but at the same time, you’re exhausted in the evening and not as sharp when at work.

Maintaining deep work hours suggests the problem is mostly distraction, particularly from tasks that feel like work but aren’t your main source of value.

The Most Important Task method works when you have a few hard tasks that you need to prioritze. It assumes you’ll end up working on convenient, easy tasks, rather than those that really matter. Quadrant systems that focus on important tasks over merely urgent ones, are another tool for prioritizing.

Breaking your day into Pomodoro chunks assumes the problem is that the work feels too large to get started, so you procrastinate. Small chunks with mandatory breaks focus your attention on the next mile marker and not the entire marathon.

These tendencies need not be mutually exclusive. You could, for instance, combine deep work hours with Pomodoro chunks or the Most Important Task method. What matters is that these systems are balancing the problems you’re actually facing. A sales person investing in deep work hours probably doesn’t make sense.

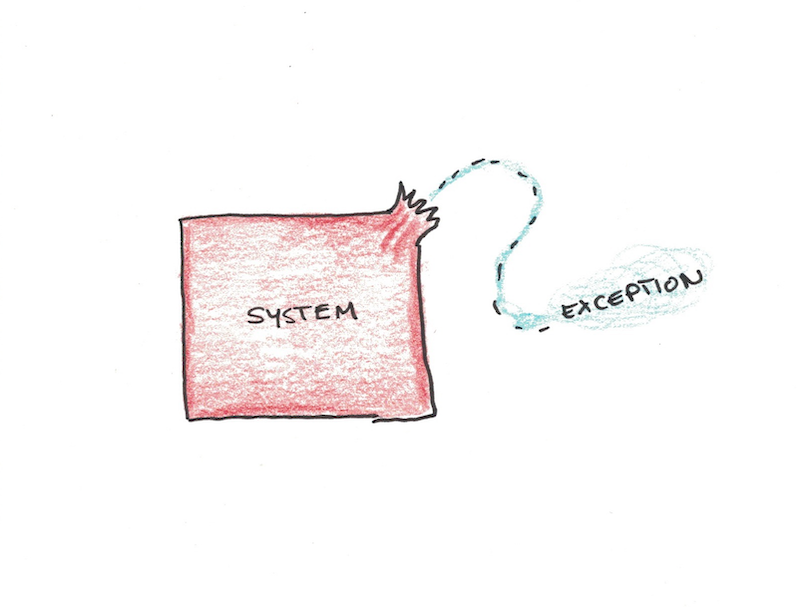

Rule #3 – The system needs a way of dealing with exceptions.

Every system, no matter how complicated, will create situations where it no longer makes sense to follow the guidelines it sets.

What’s needed, then, is a way of handling exceptions to the rules without making so many ad-hoc adjustments that the original system is rendered meaningless. Unfortunately, there’s no way to create a list of such meta-rules since if there were, they could simply be included into the original system.

For instance—let’s say you’re a writer. You have a bunch of tasks on your plate for the day, but all of a sudden you get a really good idea for an essay. You should probably start writing now or you’ll lose your train of thought. What should you do?

There’s no “correct” answer to this situation. For some people, getting enough good ideas for writing may be the major problem in their work. For them, it makes sense to put on hold lower priority work to start writing as soon as inspiration calls. For others, they may waste days chasing ideas rather than doing the boring stuff that needs doing.

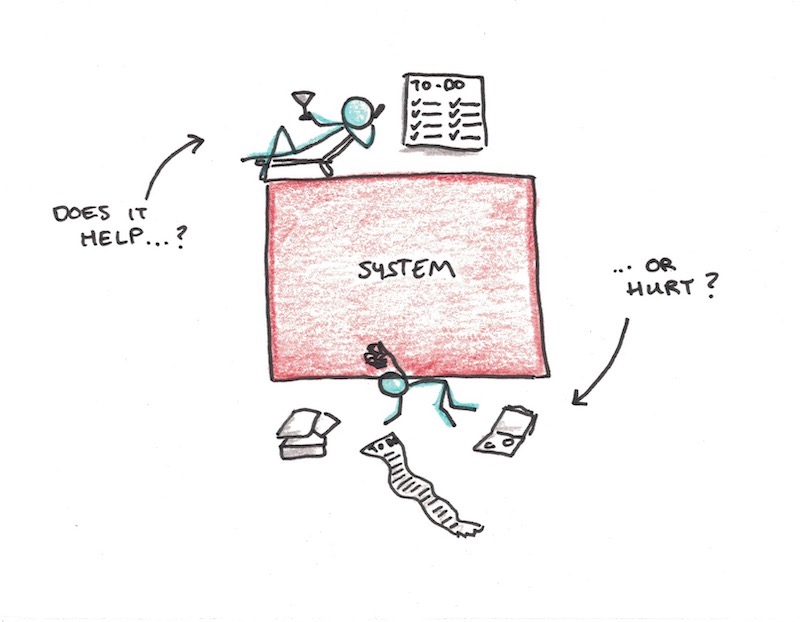

In this sense, the “correct” answer is to develop self-awareness. Does this exception to the basic rules I’ve set for myself buffer against an unproductive tendency or support it? If this exception is made into a new rule, would it strengthen or defeat the system I’m trying to create?

This may sound finicky, but I’d argue that true success with systems involves making numerous such slight exceptions which become a part of the system themselves. To use a system means not only to follow its basic guidelines, but develop a skill of handling exceptions to the system that make it more useful, not less.

Rule #4 – A good productivity system shouldn’t “feel” productive.

Okay, this one requires some explanation. In short, the problem with aiming to “feel” productive rather than “being” productive is twofold:

- Feelings are defined by relative contrast, not absolute measurement. You feel productive when you’re getting more work done than normal. But if you’re successful with a productivity habit, what’s “normal” should shift. Relying on feeling productive then creates an inescapable treadmill where if you’re not constantly doing better than what feels normal, you feel like a failure.

- Feeling of productivity is often tied to a feeling of exertion. This leads to expending a lot of effort in the beginning with a new system, getting a lot done, and then being disappointed when you can’t sustain that.

A good productivity system should, when working properly, feel like nothing at all. It should just be an invisible part of your routine. If it is conspicuous, it’s probably not a habit yet, or it’s creating friction with parts of your life in ways that it shouldn’t.

If you don’t feel more productive, how do you judge your productivity? The obvious answer is that you should get more work done with the system than without it. But even this can be misleading because in the short-term it’s always possible to just work really hard and burn yourself out.

The better, long-term answer for evaluating your system ought to be that when you look back at the last quarter, year or decade with the system, you’ve been making a lot of meaningful accomplishments. If this is happening, then how the system feels on a weekly or daily level is totally irrelevant.

Rule #5 – If your work changes, your system should too.

For some, work will be consistent enough to not need major changes. You simply stick to the same system and you’ll get the results you want.

For me, I’ve found that as what I’m trying to do changes dramatically, I often need very different approaches to work on things:

- In college, I often relied on Weekly/Daily Goals. My work was mostly a set of fairly concrete and predictable tasks that needed to be finished to stay on top of things.

- During the MIT Challenge, the tasks themselves were larger and more ambiguous. My daily goals would have looked like, “Work on class problems all day.” Setting fixed working hours made more sense here, so I could focus when I needed to, but still give myself time to relax.

- During the Year Without English, I had core tasks I set hours for, just as with the MIT Challenge. But I also had dedicated habits for doing small tasks like flashcards or listening to podcasts outside of my normal working rhythms. This helped me capture spare moments in the day.

- When writing my book, deep work hours were essential. I still had other work, so I kept to-do lists for those. But setting aside the entire morning for research and writing meant I could get a lot done. Putting this first also kept me from procrastinating by using my other work as an excuse to keep from doing hard research/writing.

- When I had to promote my book, my daily schedule looked like Swiss cheese, with up to five podcasts per day. A calendar-driven approach, where I scheduled my tasks made more sense here otherwise it would be hard to decide when was the best time to work on things.

Some features of my system rarely change. I almost always have a calendar and daily to-do list, for instance. But adjusting to a new system when I have different types of projects has been more successful for me than stubbornly trying to fit everything into a single system.

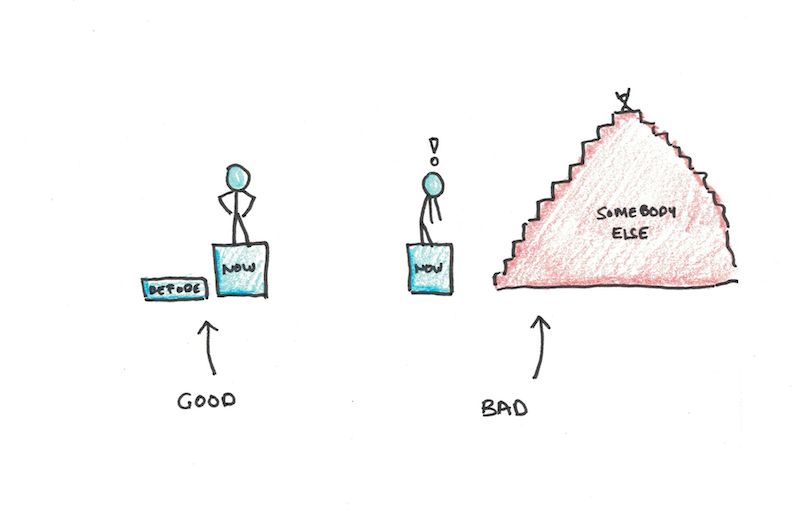

Rule #6 – Always measure against your baseline (not somebody else’s).

If you’re ever evaluating a productivity system, the right measurement to make is “am I getting more done than I was a week/month/year ago?” If you’re, instead, asking yourself, “how close am I to being perfectly productive?” or worse, “how productive am I compared to so-and-so?” you’re going to have a bad time.

The tyranny of ideal productivity is a major problem. I’ve worked with students in my courses whom set up a project successfully and were making consistent progress towards it. When I asked them how they’re doing, however, they complained that they still didn’t think they’re productive enough.

But how much is enough?

There’s certainly being insufficiently productive for your current goals or environment. If I were falling behind in my classes or failing to reach my deadlines, that might be cause for reflection.

On the other hand, there’s a perverse tendency to judge yourself against some ideal benchmark. Comparing yourself against a theoretical possibility, rather than your own past results. If you get more done than you were getting done before, the system is successful. That you’re not able to work for sixteen hours without break cannot be viewed as a failure.

Rule #7 – A system cannot give your work meaning or motivation.

A system can only shape and direct the motivations you already have, it cannot give you ones you don’t already possess.

Work that feels miserable to you doesn’t magically become exciting with the right productivity system. At best, it becomes an endurable chore.

Many failures of productivity are, at their root, deeper problems of meaning and mission in life. If you’re spending your days at a job you hate, if you’re studying a major you were coerced into rather than freely chose, if your dream job has become a nightmare, then no productivity system can fix this.

Productivity systems work better the more natural enthusiasm you have. They work like a lens, magnifying and directing the diffuse energy you already possess. The people, therefore, that tend to succeed with productivity systems already have a meaning and drive for their work. They have ambitions and recognize that getting things done efficiently is necessary for reaching them.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.