Learning isn’t studying. Studying matters, but for most of us it’s only a small slice of our lives. If you aren’t a student you might not study at all.

Learning, however, underpins your entire life:

- Relationships. Understanding your partner and knowing how to communicate.

- Work. A great career comes from being good at rare and valuable skills.

- Health. Not merely what to eat or when to exercise, but learning to stick with it long-term.

- Your sense of meaning in life. We aren’t born knowing how to live. It’s for each of us to figure out.

Given the omnipresence of learning, it makes sense to understand how it works. How can you get better at not just academic topics, but the things you do every day?

Typesetter Trouble: Why 10,000 Hours Often Isn’t Enough

One might counter that even if learning is everywhere, don’t we just learn automatically? The key to getting better is just putting in the work, right?

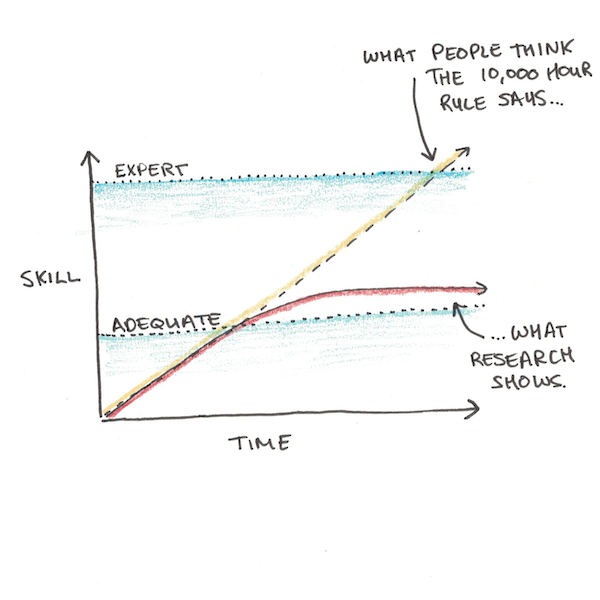

The idea that ten thousand hours is a “rule” for expertise has always been somewhat silly. First, the research the rule was based on suggested it was only an average, not a fixed amount. Second, the rule implies just getting a lot of hours is the key. In fact, the research showed pretty much the opposite.

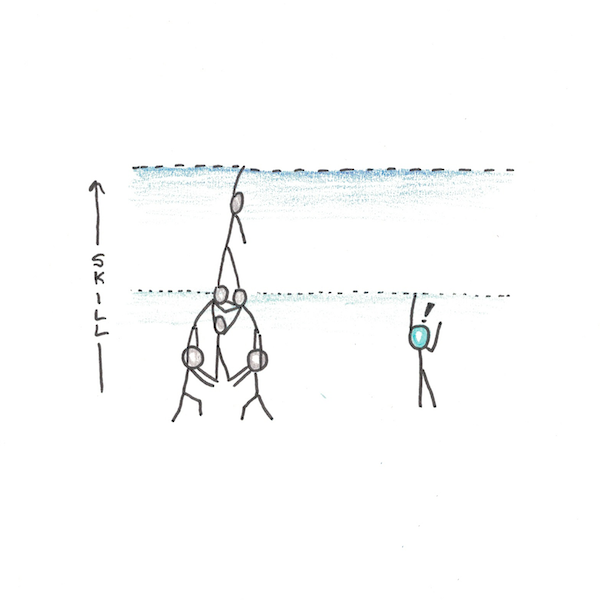

More time with a skill doesn’t lead to mastery. Instead, we reach a comfortable level of ability and get stuck. Improvement is the exception, not the rule.

Early research on professional typesetters was one of the first pieces of evidence that led to Anders Ericsson’s formulation of deliberate practice. It was found that many of them plateaued in speed, even after over a decade of experience.

Maybe they had just hit their limit though? Most tasks have a speed limit, and perhaps the typesetters had reached theirs?

Turns out this was false. Given feedback, training and financial incentives, speed improved by as much as 93%. Doing something every day doesn’t guarantee mastery, it only guarantees adequacy.

What Separates Growth from Stagnation

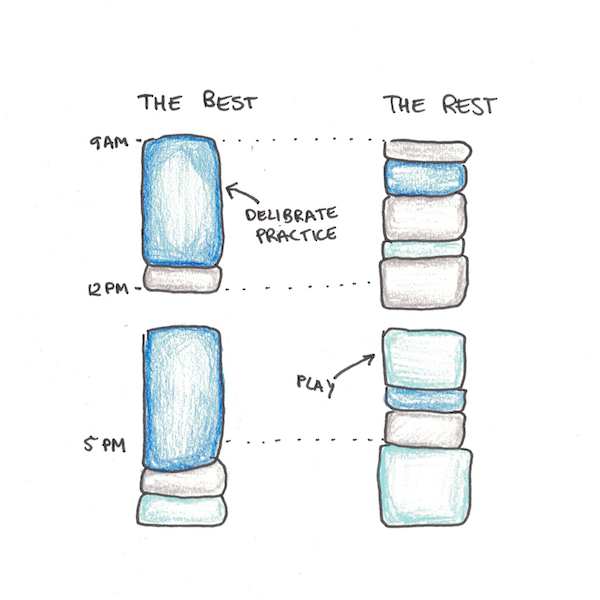

Ericsson’s insight was that practice had to be deliberate to provoke improvement.

His research on violinists found that those who went on to become concert performers didn’t practice more, but the ratio of time spent in this deliberate practice to play was much higher.

Deliberate practice means overcoming automaticity and new innovations to push performance higher.

The origin of research on deliberate practice came from studies on digit span. Digit span is the ability to remember a string of numbers and repeat them back—one in which most humans are famously limited to 5-9 items.

Working deliberately, however, one participant managed to boost his digit span from all the way to 82. He did this by creating mnemonic strategies for translating the numbers into running terms (the participant was a serious runner).

How Can You Avoid Getting Stuck?

How can you truly get a little better every day, instead of spinning your wheels?

Here’s five simple suggestions:

1. Hop to more challenging environments.

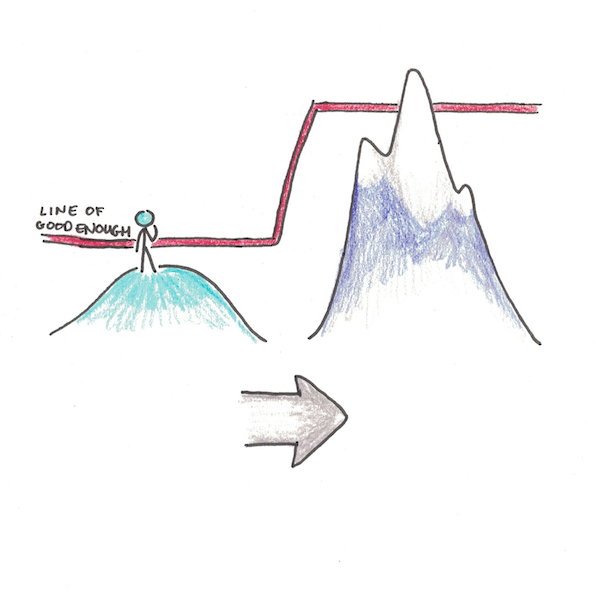

Plateaus occur because when our performance is adequate, we make it automatic. This calcifies bad habits and creates a barrier to improvement.

Upping the challenge in a new situation, where you’re no longer adequate, is a good way to switch back to the fast part of the learning curve.

2. Get a coach.

Coaching was always a central feature of deliberate practice. While coaches are available for everyone, you can still pay to get access to high-quality instruction and feedback.

If you’re on a tight budget, informally asking for feedback can often work too. The key is to be the kind of person people want to help. Be proactive and humble, willing to soak up advice.

3. Breakthroughs come from new methods.

Improvement comes in two flavors:

- Doing the same thing, but better.

- Doing a different thing, to get new results.

It’s important not to neglect the latter. Without new methods, you can easily get stuck improving something that’s obsolete.

YouTube is an incredible tool here. Learning how to mince garlic properly made cooking easier for me. But it’s the kind of thing I’d never have discovered by experimentation alone.

4. Join a community of practice.

Learning isn’t best in isolation. We’re designed to learn from the experience of others.

As a great example, look at Tetris. When the game first came out, it was played by hundreds of millions. Now, despite having far fewer players, people are much better at it. How? Because they have a community that can share methods and learn from each other.

5. Find one thing you can do better in every attempt.

The heart of deliberate practice is focused attention on a specific area of improvement. In everyday things, there’s thousands of details that contribute to the outcome. Don’t try to improve everything. Aim at a specific enhancement you could make each time.

- Cooking a recipe? What if you got better at dicing the onions?

- Writing an email? Pick one sentence and rewrite it to make it more clear.

- Lifting weight? What’s one part of the movement you could perfect?

Today’s Homework: One Everyday Thing You Could Do Better

Let’s apply these lessons from deliberate practice to something simple in your life:

- Pick one thing you do every day. It could be writing an email, folding your clothes or chopping vegetables.

- Do a Google search for ways you can do it better. See if there are any tutorials from experts.

- The next time you do it, focus on doing it a little bit better.

- Share your plan in the comments.

Small improvements add up over time. They also make the things you do more satisfying—allowing you to express a little mastery in the daily tasks you’d otherwise ignore.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.