How much should you worry about forgetting things?

In one sense, forgetting is a very real problem. How many of us could still pass exams for classes we took in college? How many dust-covered books sit on your shelf which you’ve forgotten the plot? Knowledge, like all things, decays with time.

It would be nice if there were a simple procedure for guaranteeing permanent memories. Indeed, it seems like there already are memories we have like this: a first kiss, a fantastic vacation or the birth of a child.

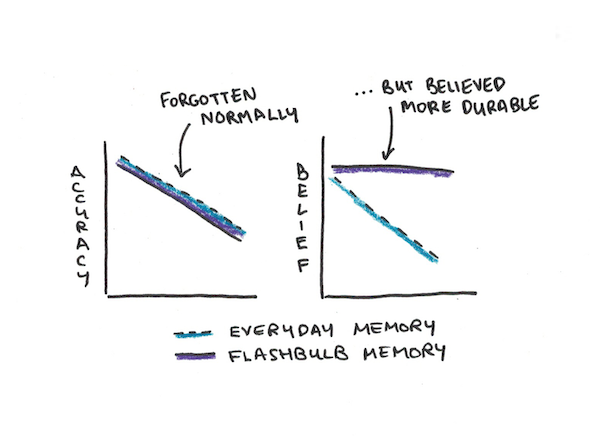

Yet, psychologists question whether these memories are as durable as they seem. On September 12th, one day after the devastating terrorist attacks, psychologists had Duke university students record their memories of the event. Later, they followed up after 1, 6 and 32 weeks to see how well they held up.

What they noted was that while the confidence of these “flashbulb” memories remained high, the decline in accuracy was similar to everyday memories. Vividness is no guarantee of permanence.

You’ve Probably Forgotten Much More Than You Realize

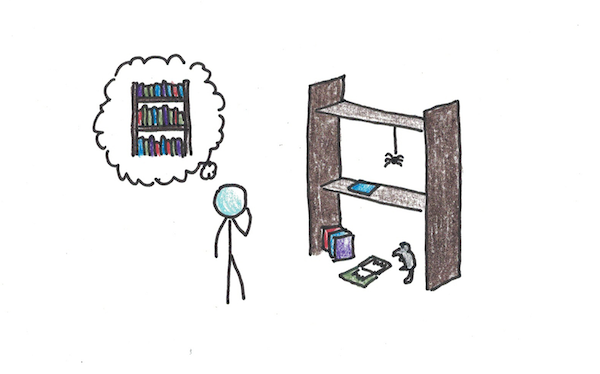

A great irony in learning is that those who remember best are the most acutely aware of how much they’ve forgotten.

Retrieval practice is well-known to be more effective than passive review for long-term memory. The research is clear, if you have to choose how to study, you ought to close the book and try remembering what’s in it, rather than just re-read things over and over.

Thus the person who uses her Spanish skills occasionally is constantly reminded of their continual decay. The person who learned it once, but never practices, confidently puts it on his resume, since his memories of the skill are still linked to when it was still fresh.

My Maintenance Headaches

This has been an acute problem for me.

On the one hand, I take seriously the problem of forgetting. After my language learning trip, for instance, I set up a maintenance schedule: once-per-week practice with each language for a year, once-per-month practice for a few years after that. I’ve done periodic programming and artistic projects to boost the skills I learned there as well.

This practice has helped. My knowledge has decayed a lot less than it would have otherwise. But keeping it as sharp as right after I’ve been practicing intensively is hard. This problem only multiplies with more things I’ve learned—maintaining one language with weekly practice is doable. Maintaining seven is a serious commitment.

This isn’t just laziness on my part, but also recognizing that each hour spent maintaining is an hour not spent learning something new. A defensive strategy that prioritizes maintenance eventually becomes a straitjacket as you don’t have time to learn new things.

Admittedly some of this problem goes away when you choose to specialize. I never worry about my writing ability atrophying. In those cases, the opposite problem is more apparent—the knowledge is so well-maintained that the routines I use can calcify, thus making improvement harder.

However, for those like me who enjoy learning a wide variety of things, the maintenance problem can be a thorny one.

In Defense of Relearning

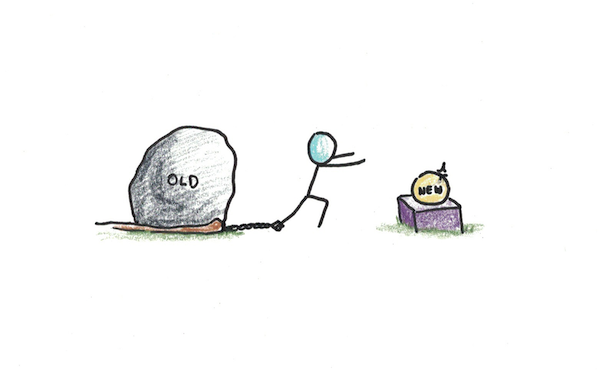

Relearning as a strategy means accepting that your knowledge for old subjects will decay and that there will be a period of work before they’re usable at their previous level.

In the past, I felt like relearning was mostly a failure of planning. The effort needed to maintain knowledge is supposed to decay exponentially, which means that if you plan it properly, you can always both learn new things and maintain old knowledge.

I’ve since become a little more skeptical of this. While the forgetting curve is certainly real, and has a decidedly exponential shape, this doesn’t automatically imply that exponentially decaying effort is required to sustain knowledge. Additionally, this would only apply to the kind of knowledge you can easily represent in flashcards, which is probably a minority of the knowledge I’d like to maintain.

Relearning, in contrast, has some good arguments in its favor:

- Relearning tends to be much faster than initial learning. The common complaint that you’ve “completely forgotten” a subject is usually wrong.

- Relearning is a form of spacing practice. Research shows that spreading out knowledge even past the point where you start forgetting stuff assists with later recall the same way that spreading out reviews does before you forget.

- Relearning prioritizes useful knowledge. If something is more useful, you’ll find more opportunities to practice it again, and thus it will be (relatively) sharp. If something isn’t as useful, it will decay more. But this is exactly what we would want with a limited budget of time to learn new things.

The Major Drawback to Relearning

I think, intellectually speaking, relearning is a perfectly defensible strategy for lifelong learning. The problem seems to be more emotional.

I’ve written before about the pain of rebuilding confidence. Your set-point for a particular skill is higher than the reality, so even doing your best with the old skill seems terrible.

I remember my first homework assignments doing MIT’s Quantum Mechanics class, several years after I had done any calculus. It was awkward. I was struggling with a lot of basic stuff and this negative feeling might have made me want to quit.

However, if you can push through this (temporary) feeling of inadequacy, relearning starts to look a lot better. It does add an additional cost to learn more advanced subjects, but there’s also a savings in not needing to worry about active maintenance.

Adopting the Attitude for Successful Relearning

The strategy I’m going to adopt with my learning going forward is offensive, not defensive. I want to enthusiastically embrace relearning opportunities.

This is sometimes going to mean failures. I remember recently I was invited to appear on a podcast in French. Interviews are harder than informal conversation, so even at my best level of French this might have been a bit daunting. Except, it had also been nearly a year without practice, with the busyness of a new book and baby.

In the end, the podcast went okay. But an offensive strategy has risks. Sometimes I might fall flat on my face as the relearning burden makes performance impossible.

Still, if I adopt a policy of not saying “no” to such opportunities out of fears of not being ready, then I’ll end up with much better language skills in the long-run, than if I make having done a lot of recent practice a prerequisite. I think my informal rule would be that if I wouldn’t have said “no” when my skills were at their peak, I won’t say no now–even if there’s a good chance I’ll fail.

Similarly, I think acting “as if” there was no forgetting from the perspective of choosing projects is helpful. Having done MIT’s intro quantum mechanics class, I’ve had ideas about going further. I didn’t get to multiple particle interactions, which seems to be the key part of the quantum weirdness I wanted to understand.

Yet, realistically, I might not tackle such a project for a few years. In which case, my QM knowledge will have decayed considerably. But picking the project “as if” there were no relearning costs, might push me to do things like this more often.

Finally, I need to accept and budget for relearning. While I think ignoring it while choosing projects is wise since otherwise some projects might be less appealing (if you envision needing a few weeks of relearning first), I do think it should affect time estimates. I definitely felt my rustiness with advanced math slowed my QM project down, yet I’m still glad I did it.

While this strategy has difficulties, I think its superior to one that tries to avoid all forgetting. I still have decades of learning left, and so I hope those are full of tons of new and interesting things, even if it occasionally means swallowing my ego and doing some rebuilding first.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.