Recently, I shared my list of foundational practices—the basic things everyone should do to live better. Of course, my choices are personal. Your list might differ a little from mine.

Most people, however, tended to agree with my choices. Foundational practices should be obvious. If they weren’t, there would be some controversy over how useful they are.

Yet there was one practice that a lot of people admitted to not doing often. People exercised, read, tracked their spending and fenced in their vices… but when it came to this practice the most common response was, “Yeah, I really should start doing that.”

The Missing Practice

This practice was having regular conversations with people smarter than you. Or, if not smarter in all ways, then a bit ahead of you in at least one dimension of life you care about.

Perhaps this omission simply reflects my audience. I attract introverted self-improvement junkies who have no trouble reading ten books a month, but find it hard to strike up a conversation with someone new.

Despite the difficulty, the value of this practice can’t be overstated. I can see at least a few major benefits of making this a part of your routine:

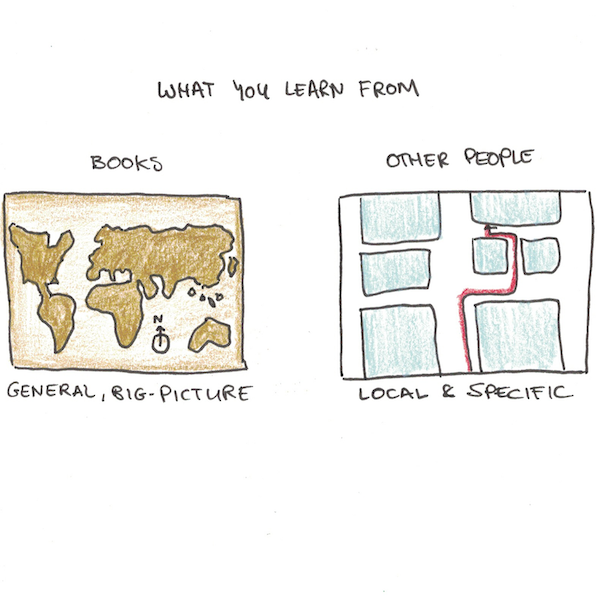

1. Books are general, conversations specific.

One person told me she reads a lot of books which fulfills a lot of the same benefits as talking to others. I agree that books can help greatly, but there are important places where these two practices don’t overlap.

The first is that books tend to offer general advice, but what you need is often highly specific. You don’t just need advice on “success” but exactly who to reach out to in your company to move your career forward. Books offer an atlas, but what you need is often a tour guide.

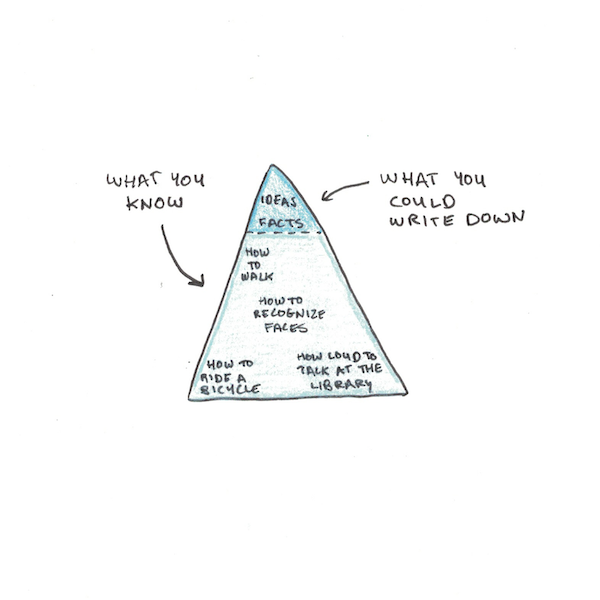

2. A lot of important knowledge cannot be written down.

What you learn from talking to others is deeper than what you could read from a transcript of the conversation. We know that human beings are uniquely social learners. And we often learn successful practices even when nobody understands how they work.

In one experiment, for instance, researchers had participants design a simple machine. Learning from the trial-and-error designs of others, they quickly made progress. Yet when asked for the theory of why their design worked, most were flat-out wrong. When you interact with people directly (or via Zoom) you not only get methods and theories, but you subtly absorb attitudes, practices and beliefs that impact your results.

3. Access matters (even if it can be overrated).

It’s a cliche to say “It’s not what you know, but who you know.” Obviously, for many professions, this is simply untrue. I’d rather have the surgeon who knows medicine, not just the guy who met a ton of people at his fraternity.

But there is truth in the idea. Opportunities are realized through other people. Even if you knew everything there was to know, you’d still benefit from talking to people since those connections would form the conduits for new possibilities.

An Introvert’s Guide to Having More (and Better) Conversations

For some people this advice is not only obvious, it’s unnecessary. If you’re more extroverted, you probably already talk to lots of people and have many friends who excel in various dimensions.

However, given the number of responses I got from readers, this is clearly a weakness for many. Thus, I think it makes sense to look at what concrete strategies you ought to use to make it easier (especially if meeting people sounds daunting).

Side note: As I write this article, the grips of the pandemic have made meeting people harder for everyone, so it’s not just introverts who are struggling!

Thus, to ensure success with the practice of having one conversation per week with somebody smart, there are a few different tactics to make it work:

1. Schedule calls with people you already know.

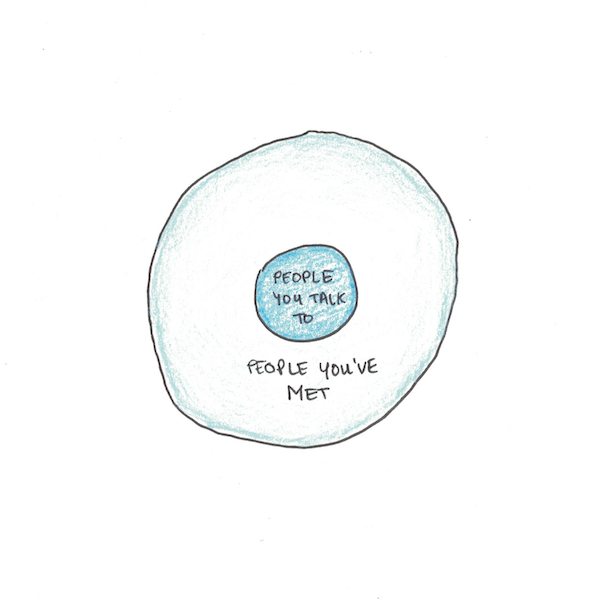

The easiest win is simply to be better about following up with people you’ve already met.

I have a friend who is remarkably good at this. He’s not the most extroverted person, nor is he the type that is always making himself the center of attention. However, he does one thing better than almost anyone else I know—he follows up.

That is, when he does meet someone, he gets their contact information and shoots them a friendly email or text a week or so later. If they hit it off, he makes an effort to have a call or coffee.

In the long run, even if he meets the same number of new people, he ends up having far more conversations. He doesn’t need to be pushy—if he messages and doesn’t get a reply, or the person doesn’t seem interested to meet up, he drops it. But the fact is, most people are passive, so even if they would be interested in conversing, they’ll rarely initiate.

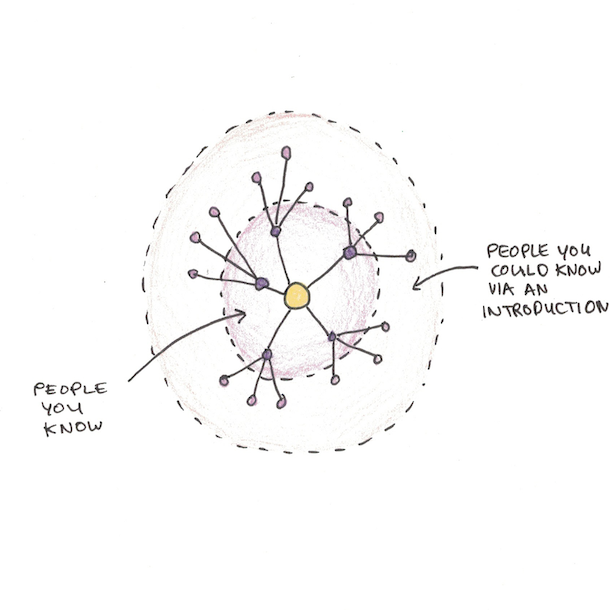

2. Ask for introductions.

The next easiest step is to ask to be introduced to people. This is particularly helpful if you’ve already identified someone you’d like to learn from. So if you’re trying to learn more about business, asking if your friends know any entrepreneurs is a good step.

When Vat and I did our no-English language experiment in China, we made heavy use of this. Starting from a few local tutors, we were able to build a network of friends relatively quickly (despite only speaking broken Mandarin) because we asked for introductions. Most people were happy to help and this strategy worked far better than trying to strike up conversations with random people on the street.

3. Reach out to like-minded people.

A final suggestion is that if you want to talk to someone, simply send them an email. It’s amazing to me how often this works. Many of my closest friendships started out this way.

In this way, having a public blog, Medium account or Twitter profile with small amount of content expressing your thoughts and ideas is helpful. This blog has helped me immensely with meeting people simply because if I want to get to know someone, they can quickly check me out and see what I think about things.

However, I also know many people with no public works who have made great use of this strategy, so don’t let being unknown stop you from reaching out.

The Real Reason People Don’t Do This

I started this article by noting that this practice, more than exercise, reading or sleep, tended to be neglected. This is strange because it’s also one of the easier practices. Exercising every weekday requires several hours. Having a conversation each week, including the time to reach out, requires less than an hour.

The obvious reason people don’t do this is that they fear rejection. What if I email someone and they don’t reply? What if I don’t know who to contact?

The easiest way to warm-up, then, is to pick people where you won’t get rejected. People you already know, or ask for introductions directly so you’re not cold-emailing people.

But the real practice is to get comfortable with not getting a response to your outreach efforts. The imagined fear is usually that the person will be angry at your presumption, or that you’ll be humiliated with a scornful reply. This almost never happens. Instead, the most common rejection is simply no reply at all.

Not getting a reply typically means nothing. The person hasn’t given much thought to your request and it doesn’t damage your reputation. Of course, don’t spam people. Don’t send multiple unsolicited requests in a row or endless emails to “follow up” when it’s clear the person isn’t interested.

I understand the trepidation about doing this because I’m hardwired the same way. I also resist doing this, but that’s exactly why I need to push myself to do it more. If you spend all day talking to people, reaching out to an additional person has diminishing benefit. But if you never do this, doing it a little bit can have enormous returns for your life. Thus, the practice is all the more valuable, the harder you find it is to do.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.