The value of focused work is obvious. Yes, deep work is often neglected. But, at least most of us agree on the importance.

Yet, I think our personal lives, even more than our working lives, are in need of a focused tune-up. Employers and clients put pressure on us to be productive at our jobs. Our personal time, in contrast, is much more easily wasted.

In the first part of this series, I explained why we need to develop a philosophy of a focused life. What does your spare time look like, ideally? How would you spend your hours if you allocated them deliberately, rather than impulsively?

A Vision of the Focused Life at Home

The goal of the focused life at home isn’t to be perfectly productive, wringing optimization out of every second of the day. Such would be the life for a machine, not a human being.

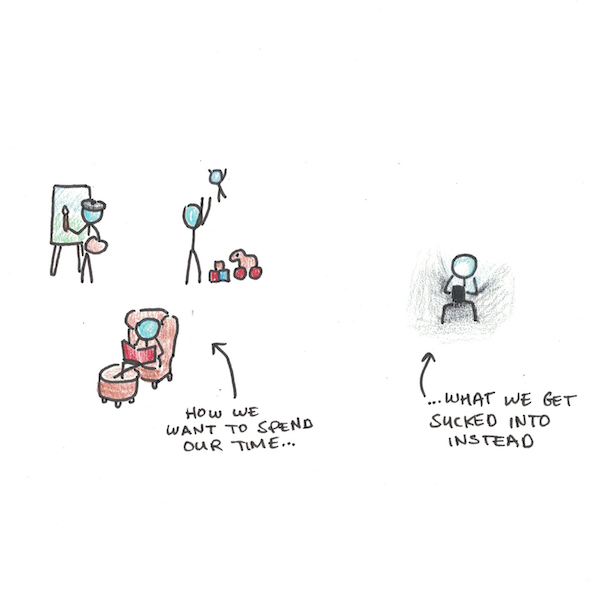

A life of focus simply means choosing where to spend your time. Do you want more time with family? More time for creative hobbies or side projects? Reading books, taking walks or doing yoga?

Unfortunately, our off-hours fail to live up to our ideal. Instead, we get caught in what I call the low-quality leisure trap. Our time gets sucked into easy and available distractions like phones, television and social media, rather than the pursuits that actually matter.

The Low-Quality Leisure Trap

From a first-person perspective, we all know the low-quality leisure trap quite well. You get a notion in your head that you’d like to be on your phone less, spend more time with your family, dedicate yourself to exercising regularly or finally learning French.

Except the day ends, you’re tired, and all of that stuff you valued seems too difficult. So you zone out for awhile, until it’s time to go to bed. You’re not satisfied with this state of affairs, but the alternatives seem too difficult.

If this were the whole story, it might simply be a sad and unfortunate truth. We want to do more meaningful things with our precious spare time, but it’s too much effort.

The Paradox of Effort

Imagine that you’ve been transported back in time two hundred years. There’s no smartphones, television or even electricity. What would you do for fun?

With many of the modern distractions unavailable, you’d probably read more books. Maybe start painting, knitting or playing an instrument. Or maybe you’d play card games with friends.

Do you suppose that these activities would be exhausting? Of course not. People did those things for fun because they were fun, and there weren’t any other alternatives.

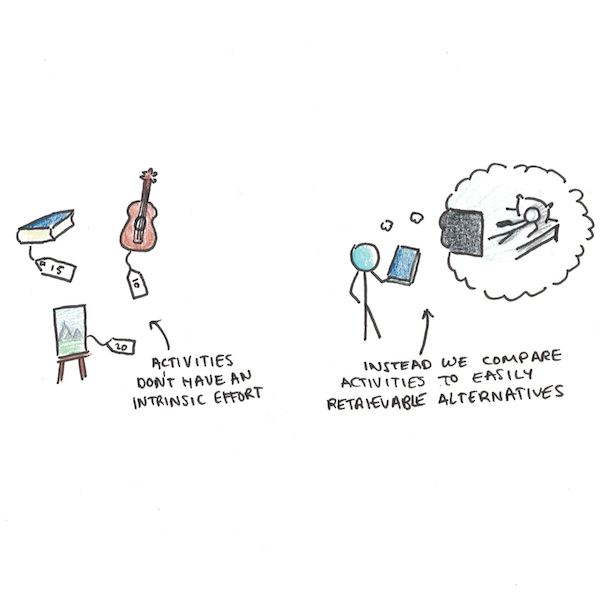

Now I’m not suggesting that you attempt to return to a pre-modern existence. But rather recognize that the effort embedded in your leisure activities isn’t intrinsic. There’s nothing intrinsically exhausting about reading a book or painting a picture. You could spend all of your time doing activities you find most meaningful and not burn yourself out.

But if this is true, why does it feel effortful? Have we just gotten lazier?

A compelling theory of effort proposed by Kurzban et. al. provides a potential answer.1 They suggest that the feeling of effort is a sensation of opportunity costs. When you’re doing anything, and an alternative activity promises to be easier and more immediately rewarding, the activity feels effortful.

This explains why people could spend all their time reading in earlier eras. They could do so because this activity didn’t need to compete with cheaper stimulation.

Thus, if you want your free time to more closely resemble your imagined ideal, you need to make the alternatives less salient. Reading will be hard when Netflix is always an option. Family time will seem boring if your phone is always within arms reach. Easier will beat better if it’s always available.

“Why Wasn’t I Doing This Years Ago?”

A common reaction among the first students of Life of Focus was to wonder why they weren’t doing this ages ago. Refocusing their personal lives meant greater time and space for meaningful activity. With the right system, you can avoid the low-quality leisure trap and spend more of your free time doing things that actually matter to you.

Yet the design of such a system is more subtle than most realize. Most of us don’t want to give up all modern entertainment, we simply want to limit it to a reasonable proportion. A stable system requires careful design much more than willpower.

Take Action Now

Today’s homework isn’t going to be a complete reworking of all your time off. Instead, let’s look at a simple change you can make.

- Pick an activity you wish you did more.

- Pick an activity you feel you do too much.

- Now, ask yourself how you could restrict the second activity to a narrow context. For instance, if you want to cut back on online news, you could restrict yourself to checking once in the morning. If you make this a habit, it won’t feel as obvious to check news in the evening, because they rely on different contexts.

- How could you inject the activity you’d like to do more in the time you’ve taken back?

Write your thoughts in the comments!

In the last lesson of the series, coming next, I’ll share what it takes to make a life of focus stick. For those interested in diving deeper, we’ll be opening for the second session of Life of Focus next week.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.