Last week I read John Doerr’s Measure What Matters and Jerry Muller’s The Tyranny of Metrics back-to-back. Needless to say, they did not agree.

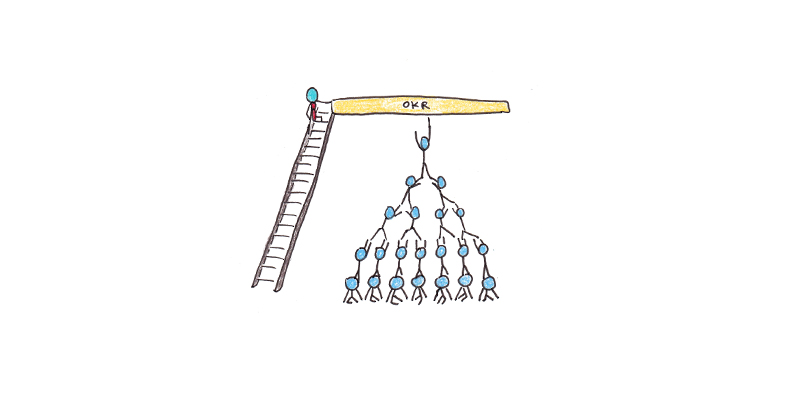

Measure What Matters is a peppy business book about the importance of setting clear goals and backing them with metrics. Acronyms and buzzwords abound. These sentences, found on page 186, might go down as the most business book-y passage of all time: “Modern recognition is performance-based and horizontal. It crowdsources meritocracy.” The bulk of the book consists of case studies. Doerr argues that, from Bill Gates to Bono, metrics-driven OKRs (objectives and key results) have a life-changing impact.

The Tyranny of Metrics, in contrast, is much more of a downer. It’s a cautionary tale, told not from the manager’s office but from the perspective of the people being managed. Muller argues that a culture of measuring everything is ruining our schools, hospitals, police and politics. When metrics replace judgment, the result is everyone frantically trying to “juke” the numbers. Surgeons avoid high-risk patients to maintain a higher success rate. Schools teach to the test, rather than educate. Police improve crime stats by reporting serious offenses as milder infractions. Instead of “what gets measured, improves,” the slogan of Mulller’s book is, “what gets measured, gets gamed.”

Which Book Was More Convincing?

Reading both of these books was an interesting case in making sense of conflicting advice. Rarely do I get a chance to read books that explicitly contradict one another in such quick succession.

Seen as a debate, Muller’s Tyranny was the more persuasive. But this is a little unfair. Doerr doesn’t make an airtight case because he mostly assumes his readers already believe metrics work. The bulk of the book is spent on getting the details right.

But before I get too meta, let’s dive into the substance of each.

The Defense: A Case for Metrics

Doerr’s case is perhaps easier to spell out. Organizations frequently waste effort by pursuing too many conflicting goals. OKRs focus efforts and get everyone on the same page.

By tying goals to measurable results—to metrics—evaluating progress becomes easy. Some companies even use “red” and “green” status lights next to their goals to immediately indicate whether they’re on track or not. As former Yahoo! CEO Marissa Mayer puts it, “it’s not a key result unless it has a number.”

The power of ambitious goals to improve productivity has a long history in industrial psychology. Making the goals public both encourages alignment and makes people accountable for their outcomes.

Doerr, for his part, concedes that it can be problematic when goal-setting becomes an obsession. He mentions the Ford Pinto’s deadly design, where attempts to hit low-cost metrics cost lives and Wells Fargo’s fake account scandal. In both cases, the pressure to measure up to metrics led to ethical pitfalls.

To avoid the potential downsides of metrics, Doerr suggests:

- Do not tie metrics to compensation.

- Be willing to change your metrics if they turn out to measure the wrong thing.

- When both quality and quantity matter, add more metrics to balance your current ones.

Overall, however, Doerr sees metrics as an essential management tool. At the end of the book he helpfully lists some “traps” new adopters of OKRs succumb to. But the list seems more to dispel problems of lukewarm adoption than actual adverse side-effects. The idea that metrics might be gamed isn’t even mentioned.

The Prosecution: Do Metrics = Tyranny?

Muller isn’t against all measurement. Instead, he’s against what he calls “metric fixation,” the obsession with numbers that leaves no room for qualitative assessment. While this doesn’t leave us with a clear rule separating when metrics work and when they don’t, that’s part of his point. Human judgement, not just data, is needed to make good decisions.

Muller gives a few key arguments:

- Tracking many metrics can be costly—and can take away from actual work.

- When pressured to hit their numbers, people will game the system.

- Transparency, the need to account for all decisions in terms of public numbers, removes the possibility for professional discretion.

- Tying metrics to rewards and punishments eliminates the intrinsic motivation that competent professionals have to do their job well.

Muller believes numbers create a deceptive aura of objectivity. It reminds me of a quote I heard once, “Nobody believes a model except the person who built it. Everybody believes the data except the person who collected it.” We tend to think of data as representing objective truth. But it was all categorized, coded, trimmed and tabulated by some guy with a clipboard. Ignoring the qualitative creation of data, we lend it an authority it doesn’t always deserve.

Charities end up worse off from the quest for metrics, Muller argues. Not-for-profit sectors suffer under constant claims for more data, accountability, and transparency because there’s no obvious stopping point. For-profit businesses, however, stop collecting ever-more data when it starts to hurt the bottom line.

Reject, Ignore or Integrate?

Faced with such conflicting views and advice, we have a trilemma:

- We can reject Doerr’s book as hype.

- We can reject Muller’s pessimism for failing to offer an alternative.

- We can try to integrate the two somehow.

The first two are the most straightforward answers, and I suspect the approach most would take. Honestly, it’s the approach I typically take. I don’t typically try to reconcile every book written by a doctor with one written by a naturopath—nor do I synthesize every management concept with its Marxist critique. Doing so would be more time-consuming than edifying. Ultimately, we always reject some arguments without a hearing simply because they lie too far outside of our worldview.

In this case, however, I found myself persuaded by both Doerr and Muller. The two books fought valiantly in my mind, even if neither delivered a knockout. That leaves option #3—try to integrate.

Three Strategies of Integration

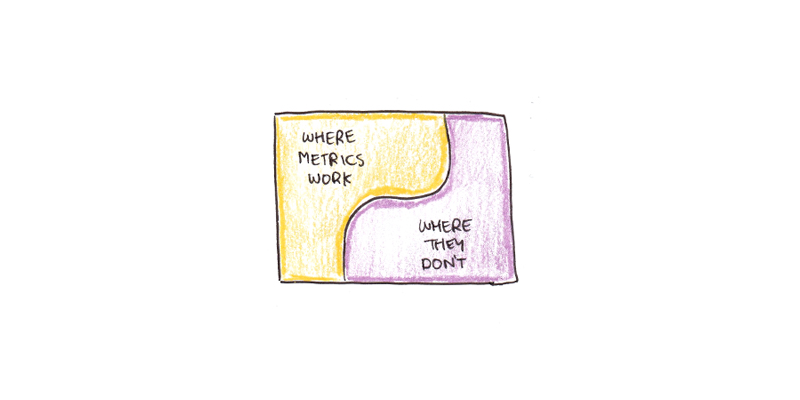

There are several strategies for getting conflicting ideas to gel together. The first is what I’ll call the strategy of non-overlapping magisteria. This is an approach taken by many theologians, to reconcile the transcendence posited by divinity with the seemingly mechanical universe posited by science. If religion and science simply deal with different things, there isn’t any conflict.

In this approach, we accept both arguments are correct but apply in different domains. Muller himself admits he’s not against all measurement, but “metric fixation.” Likewise, Doerr’s title claims we need to “measure what matters”—implying that we ought not to measure the irrelevant. Thus, there appears to be room for compromise.

This strategy might even work. Muller’s critiques focus mostly on not-for-profits, whereas Doerr is concerned with big business (particularly tech). Applying this strategy is complicated a little by both authors claiming the universality of their positions, which would leave us with a stalemate. Neither argument conquers, and we’re left with metrics for tech companies and maybe a little more caution when quantifying police departments.

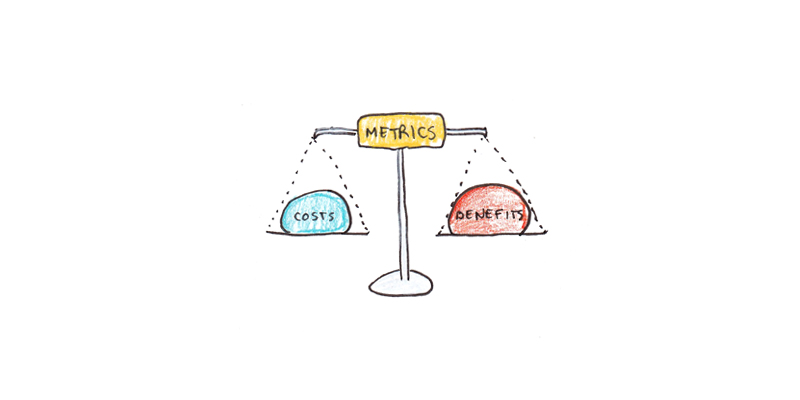

Another strategy is simply to look at trade-offs. Metrics both inspire effort and encourage corruption. They allow for progress on easily quantified goals and may be damaging to more qualitative ones. Like a potent medicine that cures disease and also creates side-effects, each metric needs to be carefully considered in light of the trade-offs.

Trade-offs are a less satisfying answer because they require weighing many possible effects for each individual case. Still, sometimes this assessment is unavoidable. Life is complicated. Why should we expect convenient solutions?

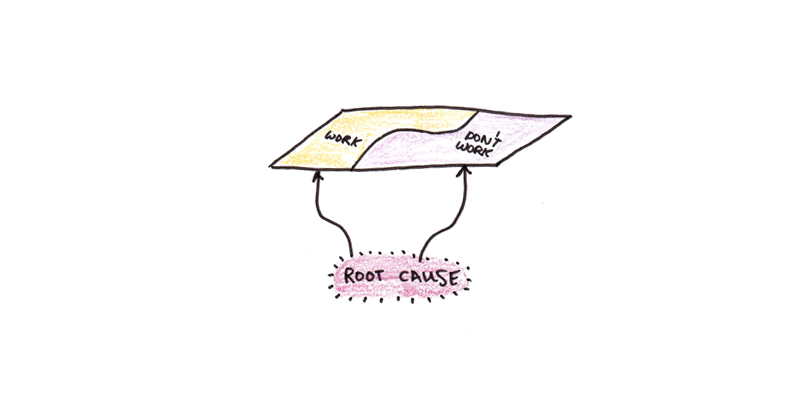

A final strategy is to posit a uniting principle. Maybe the debate about metrics is epiphenomenal to something else. The root cause is deeper and the effects of metrics are merely symptoms.

Muller’s anti-metric examples all point to bureaucratic dysfunction. People try to game their numbers because they’re powerless to push back against them. Doerr’s view assumes that when a metric mismeasures, management is promptly informed, and the strategy is easily adjusted.

This suggests to me that organizations have an internal level of vitality or sickness. Layering goals and metrics on a healthy organization increases effectiveness by aligning people to work toward a shared goal. The same strategy, applied to a sick organization, robs people of the last shreds of autonomy they had to do a job well for its own sake.

Of these three attempts at integration, I’m most inclined to the third, but trade-offs or non-overlapping magisteria might be real too. Culture seems to lurk behind the success or failure of many management approaches in ways that can be difficult to reduce to a particular method or technique. In this sense, metrics are no different from Lean, Agile, Six-Sigma, or any of the other practices du jour. Metrics are a tool for healthy organizations, but get twisted when applied to sickly ones.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.