A key strategy for getting better at things is hill-climbing. The idea is simple: try different things, keep doing the things that work, stop doing those that don’t.

The strategy is named because you can envision it as finding the highest spot in a landscape filled with fog. You can’t necessarily see the highest point, but you can always walk uphill.

Most of the time, this approach works fairly well. It likely explains how we get better at many things simply by doing them repeatedly. Where this strategy runs into trouble, however, is when you need to do something worse before you can do it better.

Interestingly, learning itself seems to be one of these situations. The actions that improve your short-term performance on a task don’t always create much long-term improvement. Since short-term effects are easier to notice, this can create a trap. Students choose strategies that make them feel like they’re learning the material but fail miserably when the exam comes.

Psychologist Robert Bjork addresses this issue by calling for desirable difficulties: actions that appear to work worse in the short-term but work better in the long run. These include:

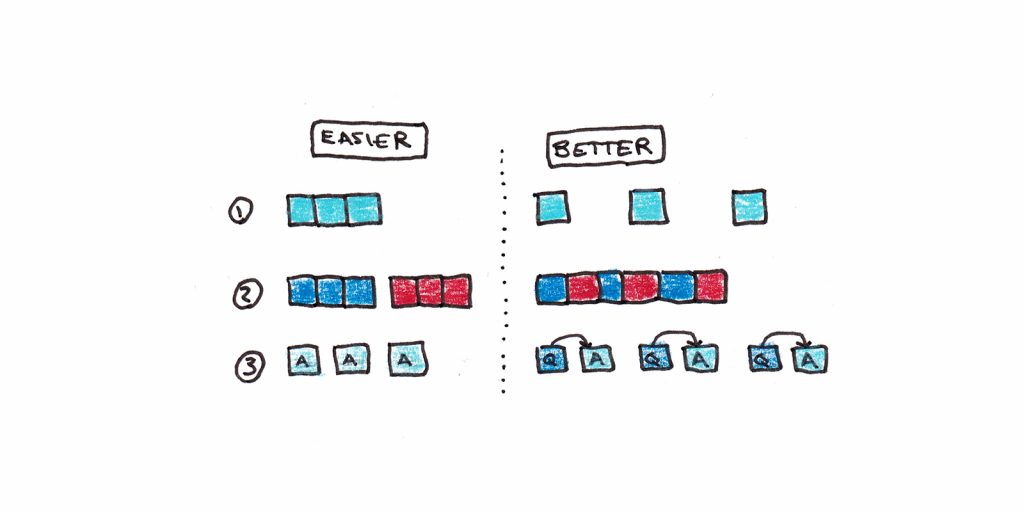

- Spacing. Imagine you have to choose between practicing something ten times in a row vs. ten times spaced out (over hours or days). The first feels easier—you will perform better immediately after practice. The second is harder but results in more permanent memory. Yet students avoid spacing, in part, because it feels like it doesn’t work as well as cramming.1

- Variability. Say you’re learning tennis shots. Should you perfect your forehand swing before moving onto the backhand? Or mix both up at the same time? Intuition argues for mastering one thing before moving onto the next, but research suggests otherwise. Variable practice tends to result in better retention and transfer than blocked practice.

- Testing. Should you re-read or do practice questions? Students overwhelmingly favor re-reading as a learning strategy. However, practice testing is one of the most effective learning methods that has been systematically studied, while re-reading is one of the worst.

What Makes Difficulties Desirable?

The exact mechanisms behind the value of desirable difficulties are still being debated.

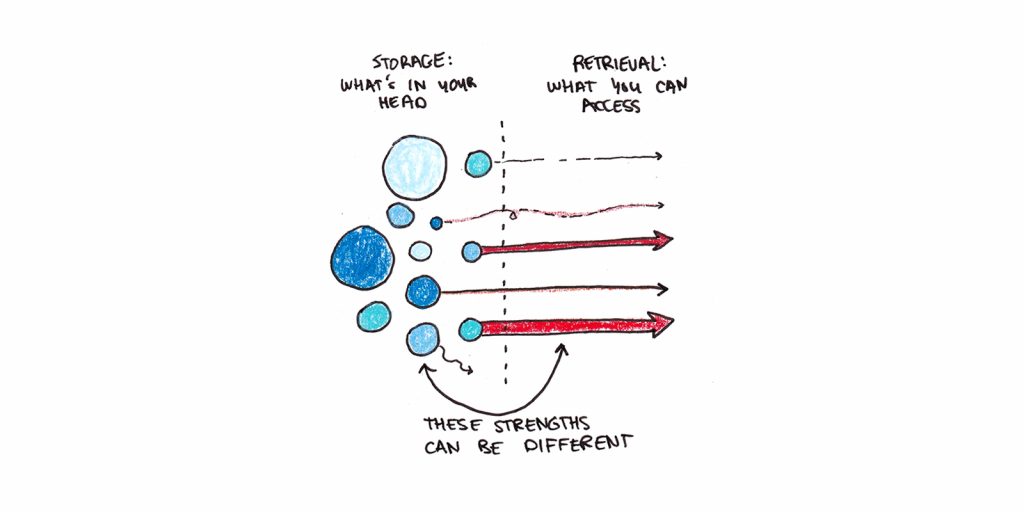

Bjork argues that the benefits come from the difference between storage strength and retrieval strength in memory. In his theory, what we learn is never erased from our minds. Instead, we forget things as our ability to retrieve them becomes weaker through competition with other memories.

This theory says that successful access to hard-to-recall memory boosts retrieval strength more than if the memory was easier to access. It’s as if your brain is saying, “Whoa! That was important and I barely remembered it! Better strengthen that connection.” Easy memory access (say because you just immediately learned it or had the answer in front of you) sends the opposite signal, with correspondingly less benefit.

Even a failure to remember isn’t always a bad thing. Mistakes and errors made while learning can be damaging to long-term performance. Still, they may also contribute to eventual learning provided the correct answer is given promptly.

Contextual Interference and Noticing Contrasts

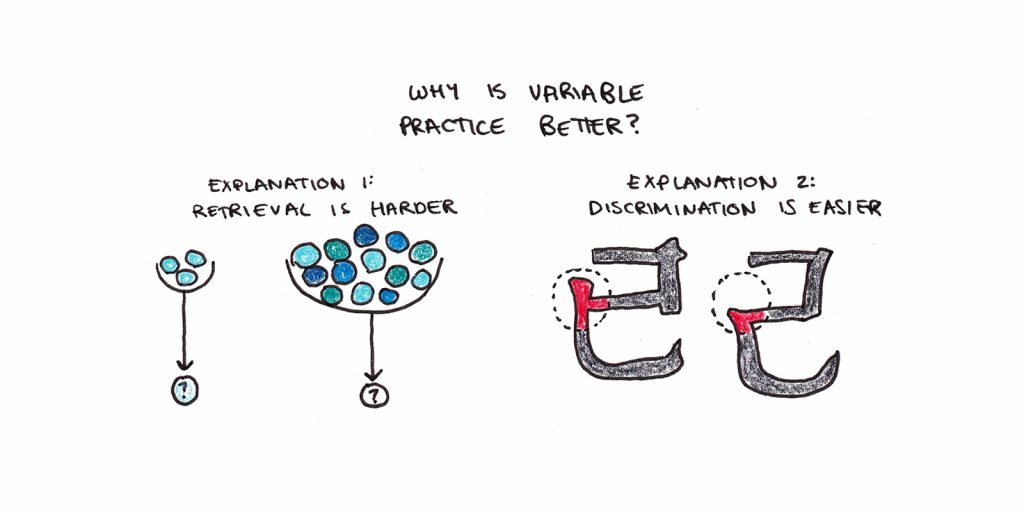

While Bjork’s theory of retrieval vs. storage strengths helps explain the three main desirable difficulties mentioned above, there’s another possible benefit to practice variability. When you mix practice between two similar ideas or concepts, you’re better able to notice the difference between the two.

I can remember a good example of this when I was learning Chinese via flashcards. Some characters are very similar. Learned separately, it’s tough to notice the actual distinctions between, say, å·² and å·±. However, the difference emerges if you put the cards right next to each other, and it becomes much easier to focus your attention on it.

This discriminative account in favor of variable practice holds true for many problem-solving skills. Math problems are often taught in a blocked fashion. You learn some problem type and do it repeatedly until you’re good at it. Then, you move onto a different type of problem and repeat the same process. The issue with this blocked approach is that it doesn’t let you practice telling apart the different types of problems because, in each case, it’s obvious.

We can zoom out even further. When taking an exam in a high-school math class, you know that whatever questions you are asked must be from one of the topics you studied that semester. However, you don’t know whether a real-world problem you face can be answered with math you’ve learned from classes. This is why transferring math skills to real life is so tricky.

Are All Difficulties Desirable?

Some difficulties contribute to greater learning. But not all do.

Work on cognitive load theory points out that many activities which increase the effort involved in learning tend to result in worse outcomes for typical students. These activities include solving problems you haven’t taught how to solve, having to split your attention between different sources of information to understand an idea, or having redundant information you need to ignore to get at the answer.

The value of desirable difficulties seems to lie on a continuum. When you’re new to a subject or idea, you need clear explanations, examples and immediate feedback to get the initial pattern into your head. Once in memory, however, desirable difficulties make practice more efficient.

This suggests that there exists a zone of optimal learning. This zone would be challenging, using up nearly all of your available mental bandwidth. But it wouldn’t be so difficult that you consistently fail in applying what you had learned.

The challenge of learning is that our reward system tends to push us away from this zone of optimal improvement through its simple pattern of maximizing immediate performance. Instead, we find ways to make things easier for ourselves now, even though this limits our growth in the long term.

Footnotes

- The other explanation, of course, is that students cramming before an exam don’t care whether they remember the information later. While there is some truth to this, studies have shown that students typically misjudge how much they learn in the two conditions. This suggests a cognitive illusion is also to blame.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.