Working hard all day doesn’t matter if it’s on the wrong tasks. The most critical factor in your productivity is what you decide to work on.

The question of what to work on is under-discussed. There’s plenty of advice on getting work done: setting up good habits, creating productivity systems, project management and planning. Yet, there’s relative silence for the crucial decision of which projects to pursue.

Choosing what to work on is hard because you can’t know in advance how any project will turn out. If you knew what perspective was most worthwhile, the right choice would be obvious. It would simply be a matter of doing the work. But these choices exist outside of any particular vantage point. We don’t have this information, and we have to choose anyway.

Ruling Out, Ruling In

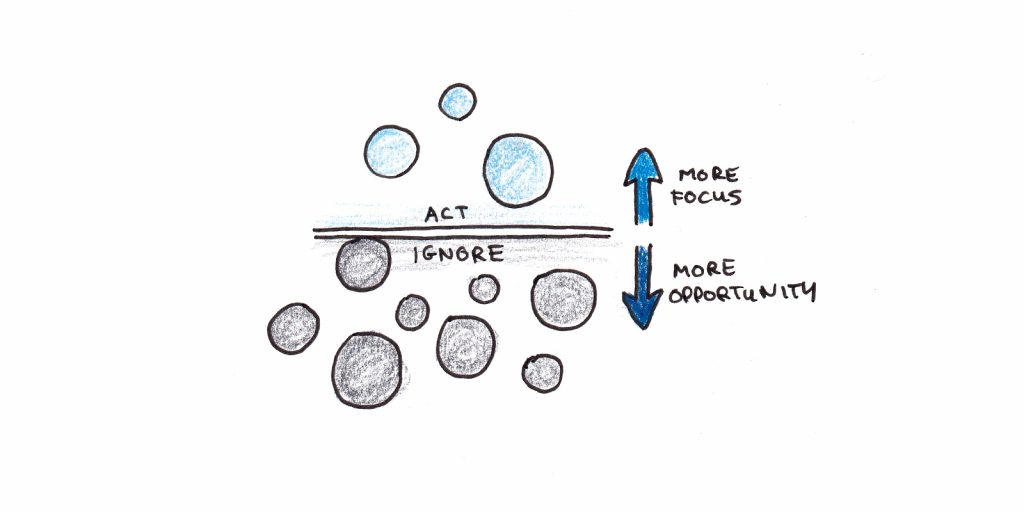

A fundamental distinction is between having too many ideas or too few.

Too many ideas creates the problem of prioritization. You need to find reasons to disqualify projects. Evaluate your current activities and cull those that don’t make the cut.

Too few ideas can leave you feeling stuck. You want things to be better, but nothing pops out as worth pursuing. As a result, you put half-hearted efforts into tasks you’re not sure will work.

The “right” quantity of ideas isn’t a given. Instead, it’s a mental threshold for what’s worth pursuing. Dialing it up forces you to focus, and dialing it down lets you explore more options. Plans often generate ongoing or future commitments. Thus, there’s often a lag between when you realize your threshold is off and when you can adjust it. Whether you’re set too far in one direction may feel obvious, even as you struggle to change it.

Both reason and intuition factor into your settings here. Feeling burned out or bored can cause you to adjust. But so can looking at your calendar and realizing, actually no, you can’t take on another client.

Coming Up With Ideas

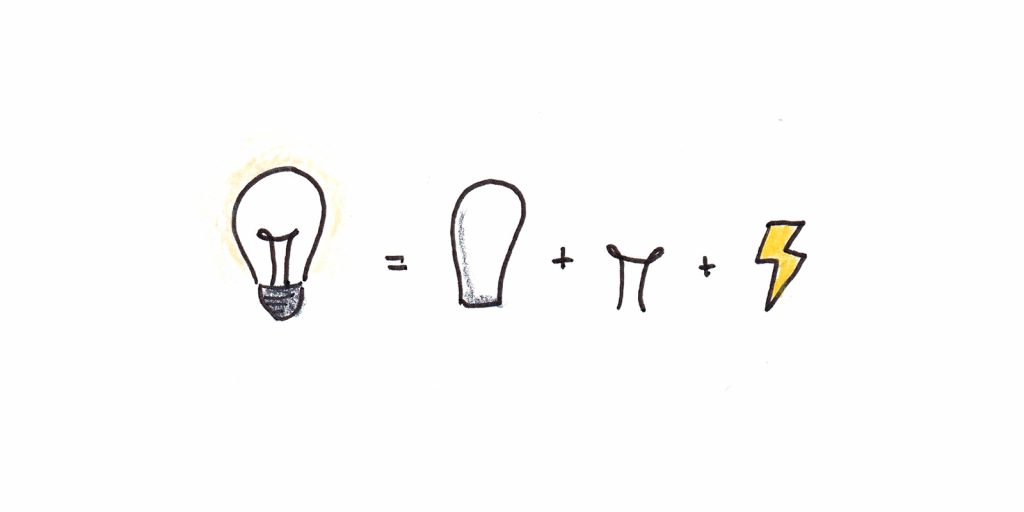

The origin of ideas often seems mysterious. How can you force yourself to have a creative spark?

Except, in practice, most ideas—even groundbreaking ones—tend to be derivative or incremental. Even ideas that look original usually start out as a permutation on something already extant. Given background and context, even the most radical suggestions look like incremental steps.

This suggests that the best way to have better ideas is to expose yourself to more ideas. Which ideas? The ones used by people who are accomplishing things in roughly the direction you’d like to go.

Find people who are achieving the sorts of success you’d like for yourself then ask what type of projects they pursue. If you can extract the general idea behind these projects, and why they worked, you’ll narrow the space of possibilities considerably.

Making the Choice

A threshold for action is a crude way for filtering your projects. Advice to “do less” or “do more” misses the crux of the issue. Which efforts should you drop? Which ones should you undertake?

Having adjusted your threshold, and hopefully immersed yourself in a range of possible idea templates, now you need to cross over from a notion to a commitment.

A commitment can come from either direction. You can lower your threshold for action, generate a new idea and decide to pursue it. Or you can tighten your standards and commit to focusing on a pursuit you are already engaged in. Either way, the decision remains.

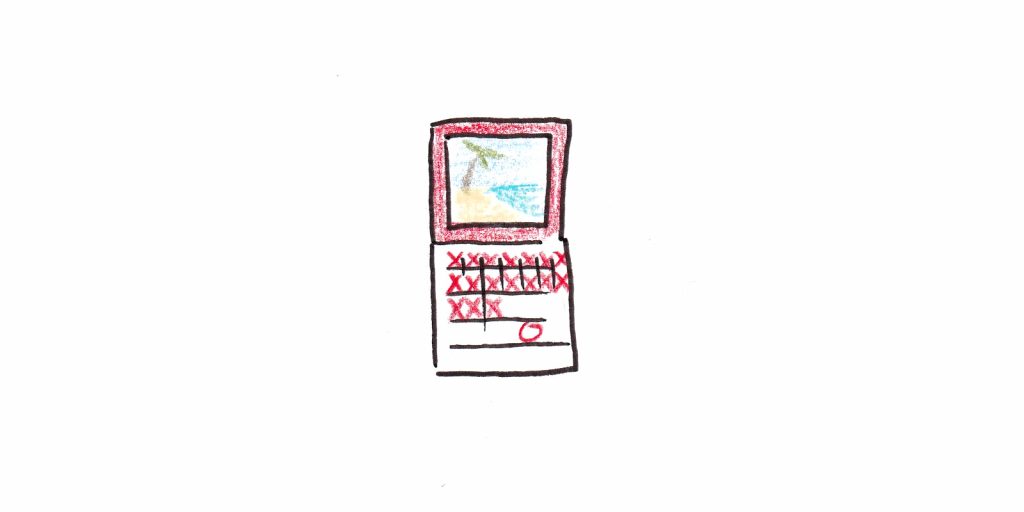

I find it useful to separate deciding from executing. The act of deciding needs to be realistic, perhaps even somewhat pessimistic. Executing that decision needs an almost irrational confidence and headstrong spirit. Failure to separate the two tends to result in impulsive choices and irresolute action.

For instance, the decision to start a business needs to be clear-eyed about the risks, your plan, and your odds of success. However, once you start that business, you need to be zealously committed to doing everything you can to make it work.

One way to help manage these two conflicting mental states is to separate them in time. Make a decision, and don’t let yourself change it for a month. The delay forces you to stop second-guessing yourself when you need to work. The nearby offramp helps you avoid worrying that you’re committing indefinitely to a potentially ruinous choice.

Finding a Path and Walking It

Much of life boils down to figuring out a path for yourself and then getting yourself to actually walk it.

It’s easy to dismiss either half of the problem. If the path seems obvious, you might think everyone who fails to walk it is simply lazy. Or perhaps you can’t find the path, so it seems everyone walking forward is a delusional striver.

But both halves of the problem interact. We often fail to stick to our plans because we’re not confident in our chosen path. And we fail to find paths forward because we don’t try enough things to find our footing.

Decision and action are always combined. The challenge is taking the next step.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.