Learning, it seems, is optimized for both humans and machines when we succeed around 85% of the time. From a recent paper by Wilson, Shenhav, Straccia and Cohen:

In many situations we find that there is a sweet spot in which training is neither too easy nor too hard, and where learning progresses most quickly. […] For all of these stochastic gradient-descent based learning algorithms, we find that the optimal error rate for training is around 15.87% or, conversely, that the optimal training accuracy is about 85%.

If you’re always successful, it’s hard to know what to improve. If you constantly fail, you won’t learn what works. Only when we have a mixture of success and failure can we draw a contrast between good and bad strategies.

These findings agree closely with the 80% success rate found by Barak Rosenshine in his study of successful classrooms, despite coming from a completely different theoretical background:

In a study of fourth-grade mathematics, it was found that 82 percent of students’ answers were correct in the classrooms of the most successful teachers, but the least successful teachers had a success rate of only 73 percent. A high success rate during guided practice also leads to a higher success rate when students are working on problems on their own.

The research also suggests that the optimal success rate for fostering student achievement appears to be about 85 percent. A success rate of 85 percent shows that students are learning the material, and it also shows that the students are challenged.

How You Can Apply the 85% Rule

Imagine you’re studying for a test by doing practice problems. You can apply different amounts of support to calibrate your success rate. The easiest way to solve the problems would be to do them with an open book and worked examples or solutions in front of you. The hardest way to solve the problems would be to work novel problems under test-like conditions with the book closed.

The 85% rule suggests that you should fine-tune the amount of support you use depending on the success rate you’re experiencing. If you’re getting more than one out of every five problems wrong, you might want to add extra help. If you’re getting nearly all the problems right, it’s time to up the difficulty.

In many skills, tasks can be graded on a scale of difficulty. Piano pieces have levels assigned to the challenge they pose. Ski slopes are ranked from green to double black. Language practice can range from simple greetings to rapid-fire debate. The 85% rule suggests growth will be maximized when we practice tasks we can succeed at roughly four-fifths of the time.

The exact percentage may vary between tasks. Reading in a foreign language likely requires understanding closer to 95% of the words to not be maddeningly frustrating. John Pasden has an interesting demonstration of how varying levels of English comprehension feel.

Of course, part of the quantitative ambiguity is that “success” can be defined in various ways. A failure to understand 20% of the words in a text isn’t 80% comprehension, but closer to 10%. Similarly, if you approached skiing so that you crash 20% of the times you go down the mountain, you wouldn’t make it very far without injuries.

Still, I think the rule offers a fairly good heuristic. If you succeed in every attempt, you probably don’t have the difficulty high enough to improve. If you fail most of the time, you will likely make more progress if you start picking smaller, more manageable challenges.

Explanations for the 85% Rule

There are many theories of optimal learning that all point to a sweet spot for difficulty—not too easy, not too hard.

Lev Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development argues that tasks slightly beyond what we can do by ourselves, but can do with assistance from others, maximize learning.

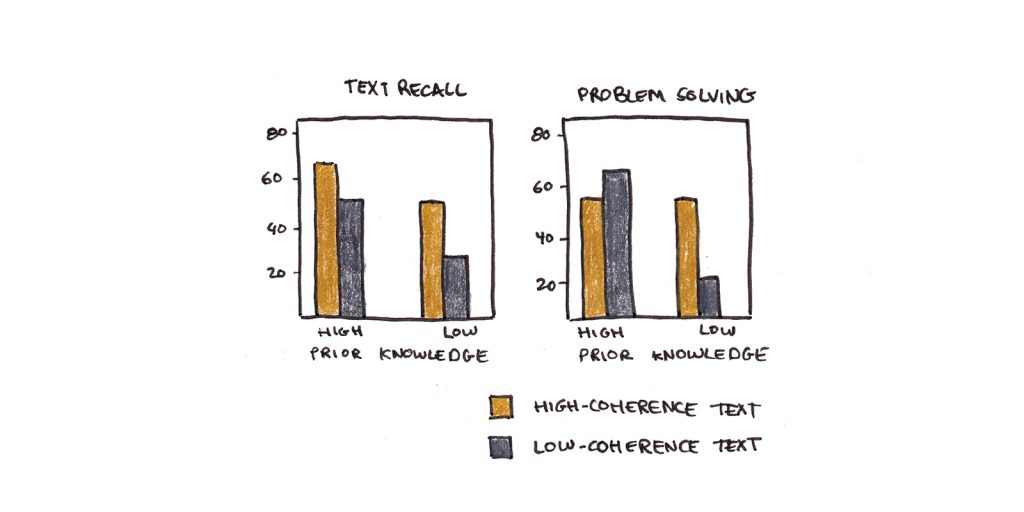

Walter Kintsch’s zone of learnability provides a similar account for text comprehension. In one study, subjects read one of two versions of a text. The first text was written to maximize understandability, with full explanations and subtitles signaling the text’s organization. The second text was written without these aids, requiring students to use inferences to understand the text’s meaning.

In tests asking questions directly from the text, both high and low background knowledge students did better on the coherent text. However, when given a test that required inference or problem solving, the students with higher background knowledge did better than students with less background knowledge when interpreting the less coherent text.

These results fit a model where, if a text mostly says things you easily understand, you don’t invest much effort into creating a mental model of what the text describes. In those cases, greater difficulty might be beneficial since the struggle it creates forces you to retrieve background knowledge. (This only works, of course, if you have knowledge to retrieve!)1

Anders Ericsson’s model of deliberate practice argues that when skills become automatic, we plateau at levels of ability far below our potential. To counter this, we need to return to the deliberate phase of learning. We can do this by picking harder tasks or setting higher goals for performance.

Robert Eisenberg’s theory of learned industriousness suggests difficulty plays a role in motivation as well. In an experiment, one group of subjects was given hard puzzles to work on. Another group was carefully matched to this group, given an easy puzzle for each question the first group got right, or an impossible question for each one the first group got wrong.

The two groups thus experienced the same success rate, but had very different expectations about the role effort played in success. For the first group, hard work often paid off. For the second group, it never did. On a subsequent puzzle task, members of the first group persisted longer than those in the second group, suggesting that they had learned to work hard at this kind of puzzle.

Learned industriousness suggests that success on hard problems can be good for us, but failure is demotivating. Once again, a difficulty sweet spot emerges where we work on problems we’re likely to succeed at, but are hard enough to encourage effort in the future.

What skills are you working on? What’s your current success rate? Should you be increasing the difficulty or finding ways to reduce frustration? Share your thoughts in the comments.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.