It’s a common opinion that we learn more from failure than success.

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible,” says Harvard Business Review. Learning from failure “fosters creativity” and helps you “become more resilient,” according to another essay. When Thomas Edison was asked if he was disappointed with his lack of results in finding a workable lightbulb filament, he replied, “I have gotten a lot of results! I know several thousand things that won’t work.”

Here, though, the feel-good opinion is wrong.

We generally don’t learn more from failure than success. In cases where there is value in mistakes, failure is followed quickly by success, rather than prolonged struggle. The reason is simple math.

Success, Failure and Information Theory

That we generally learn more from success than failure is evident from the principles of information theory.

Information theory was developed in the 1940s by mathematician Claude Shannon. The basic idea is that information is the reduction of uncertainty. Consider flipping a coin. Before I flip, there is an equal chance the outcome will be heads or tails. After the flip, I know only one of those results occurred—this halving of uncertainty results in one bit of information I didn’t have before.

The information gained from flipping a coin is symmetrical. Heads and tails are equally likely, so I learn the same amount from experiencing either event.

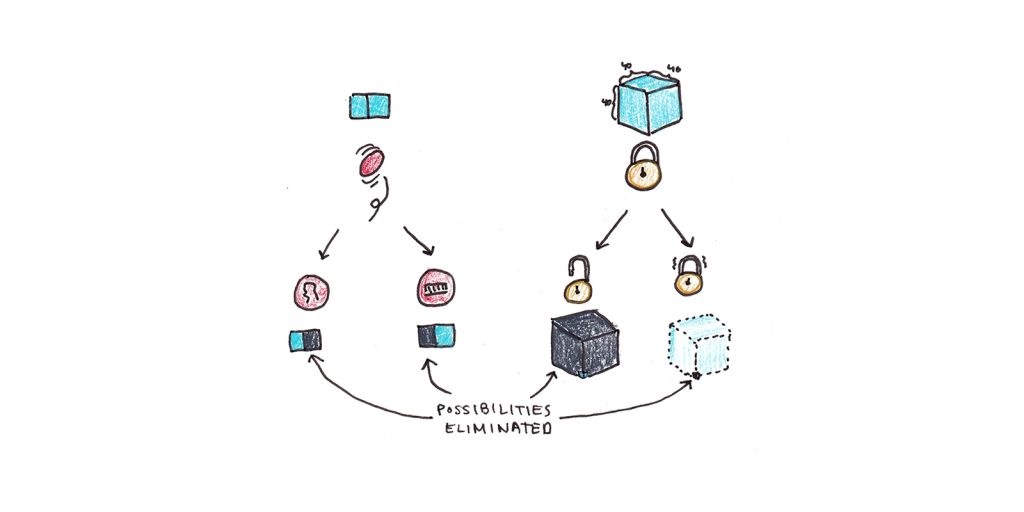

This doesn’t hold if one outcome is far more likely than another. If I try to open a 40-number combination lock with a random, 3-digit code, my chance of opening it is only one in 64,000. Failure here only reduces the space of possibilities by one—hardly any information at all. In contrast, if I had opened the lock successfully, I would have eliminated any remaining uncertainty.

In the combination-lock example, success teaches you far, far more than failure.

Running a business is like finding a combination that opens a lock. You need the right mixture of product, team, marketing, and customer needs to have a successful outcome. Failure is more likely than success—most products and businesses underperform or fail outright. Thus, you gain exponentially more information about what works when you find a hit than you do with a misfire.

In contrast, failure can be highly instructive in some domains. Plane crashes happen rarely, so when one does occur, much potential information can be gleaned about the source of the disaster. Our knowledge of piloting is so advanced that successful takeoffs and landings don’t reduce uncertainty by much at all.

Of course, this doesn’t mean a pilot learns to fly by crashing a lot. When you start flying a plane, most settings of the controls would result in a crash if unfixed. It’s simply that, society as a whole benefits from thorough investigation of plane crashes because trained pilots rarely have such severe mistakes.

Most domains of learning are like the novice pilot, entrepreneur or combination-lock. There are far fewer conditions that enable success than those that allow for failure. Thus, learning what works imparts far more information than learning what doesn’t work.

Despite Edison’s optimism, his learning process would have ended immediately had he started with tungsten instead of trying out thousands of materials that ultimately didn’t work.

Studies on productive failure and learning from errors find benefits to making mistakes in learning—if those mistakes are promptly corrected. When a successful example or corrective feedback immediately follows every failure, the information difference between success and failure is eliminated.

Outside a classroom, failure is seldom followed by a lesson telling you exactly how you should have done it.

What About Emotions? Failure Discourages Effort

Perhaps I’m being too coolly rational in my analysis here. Don’t emotions factor into learning as well? Isn’t failure a great teacher emotionally, even if it doesn’t provide informative lessons?

Here too, the boon of learning from failure is overstated.

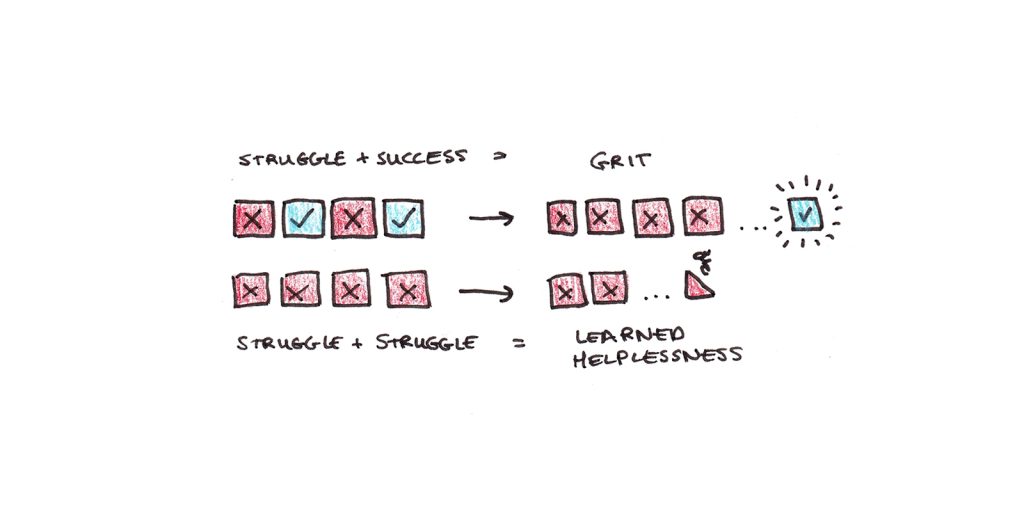

Failure is discouraging. Experiencing consistent failure lowers motivation. In extreme cases, it can lead to learned helplessness, and you stop trying even when success is plausible.

Success, in contrast, is motivating. It builds self-efficacy and confidence, which are related to greater motivation in learning. If you experience success in early mathematics, it boosts your confidence when attempting higher mathematics, so you’re more likely to persist when you experience setbacks.

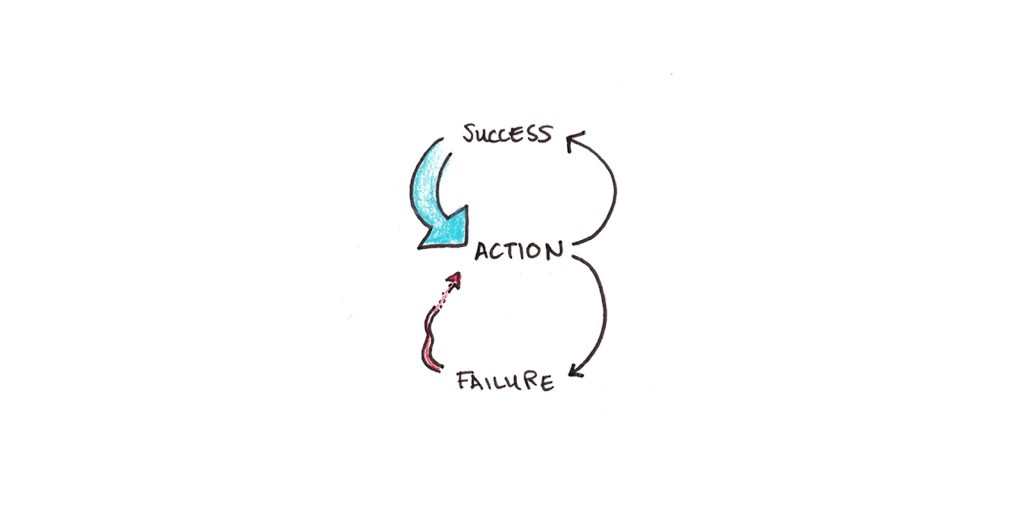

What about grit and perseverance? They matter, but it’s important not to confuse the right way to process failures (persistence) with the idea that failure itself makes us better.

Grit comes from the belief that, despite current failures, success will be forthcoming. Where does such a belief come from? I’d argue that it comes from a background of confidence, either from your own past successes or from witnessing or learning from others’ successes.

The idea that failure is inherently character-building seems dubious to me. Repeated failure requires—but it doesn’t build—grit. It’s experiencing success after persisting through failure that reinforces perseverance.

Only taking on easy problems doesn’t impart grit. But neither does consistent failure on hard problems. It’s taking on challenging problems AND succeeding in them that matters.

Overlearning from Failures

Maybe you think I’ve missed the point.

The point isn’t that failure is inherently valuable—either emotionally or informationally—but that we can’t always control when we experience failure. Thus we should adopt a positive attitude towards it.

In this case, I agree. Failure and mistakes are often unavoidable. To the extent that we can have a healthy attitude, I think leaning toward perseverance is generally wise. (Although persisting in doomed projects is an underappreciated problem.)

However, there’s another danger of advice like this—we can easily overlearn from failures.

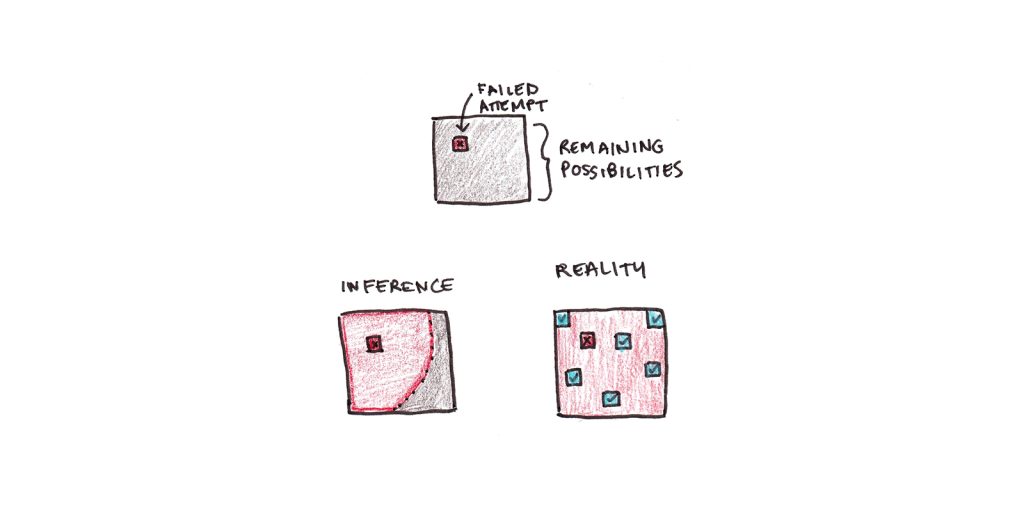

Many failures are like our combination-lock example: the specific thing we tried didn’t work. It would be disastrous to infer, after guessing 20-12-32, that the actual code couldn’t contain any of those numbers, any even numbers, or any middle-low-high sequence. Those “lessons” are overeager attempts to gain more information from the failure than is actually there.

Similarly, we can easily over-infer from our circumstances when we experience a business failure, a lousy relationship or a bad job. The actual reasons for our failure may be specific. Yet we extrapolate those to anything that resembles the original condition. A partner that cheated on you, for instance, might convince you that all partners are potentially unfaithful.

In many cases, the healthy attitude to failure is to move on. Keep a mental note of any patterns surrounding your failed exercise, but don’t expect definitive lessons about what works to emerge when success is relatively infrequent.

Planning for Success

Overall, we learn more from success than failure. Success is both more informative and motivating. When struggle is helpful, it tends to be followed by success.

Of course, success isn’t something we can guarantee. Our ignorance about what makes something successful is what makes success informative in the first place.

Even so, we can take steps to build toward success:

- Build successes in small increments. If you’ve never succeeded at a year-long project, try a month-long project. If your month-long efforts have fizzled, try a weekend. If you’ve never written a book, start with an essay. If you haven’t launched a company, try finding a single client.

- Pick challenges where success is likely, but not certain. The 85% rule for learning suggests we aim for roughly five successes (and one failure) out of every six attempts. The exact percentage is less critical than the suggestion that succeeding most of the time is our aim. If we’re failing much more than this, our expectations are out of whack, our projects are too difficult, or we haven’t gotten the training to do what we’re attempting.

- Learn the hard lessons from others first. When failure is likely, begin by learning as much as you can about what works by studying others’ success. The more you understand what the “success pattern” looks like for a particular endeavor, the less you’ll need to learn through trial and error.

- When you do fail, keep moving. Catastrophic, unexpected failures do offer lessons for introspection. But run-of-the-mill failures often don’t. Overinterpretting the lessons of failure can be just as bad as, or worse than, not learning anything from it. When failure is the status-quo, the best thing to do in the face of failure is to keep trying.

Experiencing failure can build some valuable character traits: compassion, humility and gratitude. In this sense, failures are not wasted experiences. And when we do encounter them, it’s probably best to see them in a positive light.

But, we should avoid exaggerating this silver lining into believing that the best path to success is a string of failures, especially when we can choose an alternative route.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.