How does the mind work? Why do the best writers get the most writer’s block? Is the process of evolution the key to understanding the development of thought? Here are some selections from my recent reading.

1. How Can the Human Mind Occur in the Physical Universe? by John Anderson

Given the title, you might be expecting this question to be rhetorical. As in, “How could we possibly understand something as mystical and limitless as the human mind?” Instead, Anderson offers a sincere answer to the question of, as Allen Newell put it, “how the gears clank and pistons go” in the human mind.

Anderson considers three dead-ends visited by psychology (two of which he stumbled down himself):

- Ignoring the brain. Herbert Simon and Allen Newell spearheaded this classic approach. Early information-processing theories waved away the question of how functions are implemented in the human brain. This led to theories that were similar to serial computers—but biologically implausible.

- Ignoring the mind. Another idea, eliminative connectionism, assumed we could infer higher-order mental processes from the behavior (or presumed behavior) of networks of individual neurons. To their credit, computational neural networks have worked well as pattern-associators. Still, Anderson argues these networks only model unreasonably small slices of human behavior. Understanding the mind requires integrating human intentions, memory and step-by-step thinking processes.

- Ignore the mechanism. Another dead-end is to start by assuming that the brain needs to adapt to the real world and then infer cognition based on those constraints. While Bayesian analysis can match the statistical patterns of memory, this path ultimately dodges the question of how memory actually works in the brain.

Anderson’s answer is ACT-R, his long-developing theory that I’ve previously reviewed. His research has attempted to synthesize the contributions of many different fields of psychology to present a reasonable model of how humans think. While some may scoff at the possibility of answering the question itself, Anderson’s attempt comes as close as any to unraveling the enigma.

2. Toward a General Theory of Expertise edited by Anders Ericsson and Jacqui Smith

What makes experts better than beginners? What changes in the mind to allow a grandmaster to pick the right chess move, a doctor to diagnose the right illness or a tennis pro to hit a perfect backhand shot?

The study of expertise has produce a host of replicable findings about differences in expert performance:

- Novices reason backward, experts reason forward. Backward reasoning is a process of successive goal-setting, where you start with your final goal and work backward to intermediate steps you need to take. Forward reasoning, starts from where you are and moves automatically to the end. Studies find that experts usually do more forward reasoning, characteristic of routine actions, and novices engage in the effortful backward reasoning of problem-solving.

- Novices see arbitrary pieces, experts perceive meaningful chunks. Experts see complex patterns of information that allow them to reconstruct what they’ve seen without difficulty. Novices, instead, see a bewildering array of component parts they struggle to make sense of.

- Novices rely on weak methods, experts use strong methods. Weak methods are the general-purpose tools we use when encountering novel situations. These include heuristics like hill-climbing (keep changing things in a direction closer to the solution) and trial-and-error. Strong methods are domain-specific methods that deal with particular problems.

While a host of expert-novice differences have been studied, we know comparatively less about how novices become experts.

3. The Psychology of Written Composition by Marlene Scardamalia and Carl Bereiter

The standard picture of expertise is that experts reason automatically and fluently, moving from problems to solutions in a straight line. In contrast, novices stumble through effortful problem-solving, hitting dead-ends as they work towards the answer.

Writing defies this picture.

Instead, Scardamalia and Bereiter observe that new writers exhibit surprising fluency. Novice writers frequently begin writing immediately, almost as quickly as they can put pencil to paper. In one investigation, children were astonished when told that experienced writers sometimes spend as much as fifteen minutes thinking about what they’ll say before writing.

In contrast, experts are slow, plodding, effortful problem-solvers. They frequently get stuck, experience writer’s block and struggle with writing. Despite this, they produce far better prose.

Why does writing defy the normal rules of expertise? Scardamalia and Bereiter’s answer is that novices and experts use different processes for writing.

They find that novices use what they call a “knowledge-telling strategy.”

A novice tries to recall as many ideas as possible that fit the topic and the conventions of the writing format. When given a writing prompt such as “Should students be able to choose what they study?” children try to generate sentences that fit both with the topic of scholastic choice, as well as the overall format of an opinion essay.

In contrast, they argue that experienced writers use a more elaborate process they call a “knowledge transformation strategy.”

The expert is working simultaneously in two problem spaces. The first is one of rhetorical issues (e.g., will my audience find this convincing?), and the second concerns content issues (e.g., what do I believe about this?). This back-and-forth process is effortful, but it results in better writing than is achieved by novices.

I found this book fascinating, both for providing insight into my own writing process and for offering validation for my observation that writing has gotten harder for me as I’ve gotten (hopefully) better at it.

4. How We Learn to Move by Rob Gray

How do people get good at athletic skills? The classic answer is through repetition. By repeating the correct technique over and over, we eventually perfect our golf swing, running stride, or jump shot.

Gray argues against this view, arguing that not only does repetition not work, it isn’t even possible! Instead, he argues that motor skills are a dynamic, adaptive system. We need variability in our movement and practice to avoid injury and fine-tune our motor coordination.

I’ll admit, motor skills are a lacuna in my general knowledge of skill development. So it’s hard for me to judge how mainstream Gray’s views are. Nonetheless, I found his ideas plausible, especially given how difficult it is for people to understand their own body movements.

5. Parallel Distributed Processing by David E. Rumelhart and James L. McClelland

Parallel distributed processing, or connectionism, is the idea that we need to understand how the brain is organized to understand thinking. PDP is considered a landmark book in launching the serious study of computational neural networks.

A few general ideas proposed by PDP include:

- Distributed representations. Rather than represent memories or ideas through single “tokens” or units, connectionism stresses mental representations extended over many neurons. In this way, the coding for the memory of your grandmother, high-school chemistry teacher or Brad Pitt isn’t a single neuron somewhere in your brain but a diffuse pattern of activation over countless units. This distributed representation allows for robustness, but it has drawbacks. The question of how these networks can encode relational properties (e.g., “the dog bit the man” vs “the man bit the dog”) vexes cognitive scientists and machine learning researchers alike.

- Thinking as “relaxation.” A challenge of real-world thinking is that it often involves drawing inferences under many ambiguous constraints. Serial information-processing models often result in an explosion of possibilities, which makes them impractical for commonsense reasoning. Connectionist networks avoid this difficulty by having possibilities compete with each other for expression. As incompatible ideas suppress each other, eventually the most likely option emerges. Relaxation of this kind is a major part of Walter Kintsch’s Construction-Integration theory, which I reviewed here.

- Learning through error correction. Training distributed representations is done via back-propagation, where errors are used to adjust the weights of aspects of the neural network into an optimal configuration.

This book sat on my shelf for years before I finally gave it a read. My current view is that connectionism provides a better approximation of the intuitive/sensory/low-level aspects of thinking, and symbol manipulation is a better approximation of the rational/cognitive/high-level aspects of thinking.

6. Emerging Minds by Robert Siegler

Child development has long been characterized by a staircase metaphor of progress. Influential Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget observed that children of different ages used characteristically different approaches to thinking. This tradition has continued into the information processing age, with theorists such as Robbie Case arguing that these correspond to discrete increases in working memory capacity. Staircase thinking also occurs in “theory” theories, which propose that young children have different representations of physics, psychology or the outside world than their more mature counterparts.

Siegler argues that the staircase metaphor is wrong. Instead, he argues, the field has systematically overlooked variability in cognitive development. Instead of a single way of thinking, what is impressive about people is how many different ways we have of thinking. Children often exhibit several methods for solving a problem and don’t inevitably use the best one.

This variability has consequences. Siegler argues for an evolutionary approach to thinking. Just as species aren’t neatly ordered on a ladder of creation, nor are human mental abilities explained by the staircase metaphor. Instead, a wide variety of methods compete and adapt for application through repeated exposure.

Siegler has conducted extensive investigations of how children approach problems of addition. He finds that the strategies children use evolve over time. They begin by counting from both numbers, then move on to counting from the larger number, then retrieving the answer directly from memory. However, this transformation doesn’t occur suddenly. Children use multiple methods whose frequency changes over time as they learn new tricks and memorize the answers.

I haven’t read enough developmental psychology to say whether Siegler’s book represents a new consensus or a heterodox view. Still, I find his idea interesting for suggesting that learning skills may involve acquiring completely different procedures at different stages of growth.

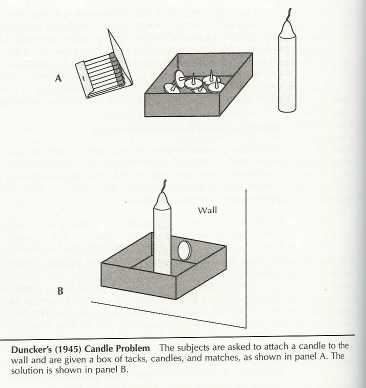

7. On Problem Solving by Karl Duncker

Decades before Newell and Simon’s book on problem solving, Duncker wrote a tight little academic monograph investigating the thinking people used when solving problems.

It’s from this book that the concept of functional fixedness appears. This is the idea that in seeing an object as having a particular function, you are less able to see it in an alternative function.

The classic experiment is his task asking subjects to fix candles to a wall, provided a box of tacks. If you put the box separately, most subjects recognize it as a suitable platform and fix the box to the wall before resting a candle on top. In contrast, if you put the tacks or candles inside the box, subjects view the box as a container and thus very few solve the problem.

I’m fascinated by Gestalt psychology. Despite being an extinct lineage in the evolution of scientific psychology, work by Gestaltists presaged much of the cognitive revolution. The Gestaltists were mostly German, and the rise of Hitler forced many of them to relocate to America, where they faced a less favorable environment to their brand of psychology. If Thomas Kuhn was right, and scientific paradigms are incommensurate (and, to a certain extent, arbitrary), I wonder if twenty-first century psychology might have looked very different had history played out differently.

Additionally, my friend Barbara Oakley has a new course focused on online teaching. If you’re a teacher, professor, or just an online video-maker, this course is a guide to the practical nitty-gritty of running a course—and also digs into the scientific details behind successful teaching.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.