I remember having a conversation with my friend Olle Linge about learning Chinese. I had already spent a couple of years studying, and while I could converse and read some books, I still struggled in more complicated situations. My progress had slowed, and I was in an awkward phase where I sometimes felt confident and other times not.

“Yeah, that’s what it’s like from now on,” was Olle’s half-joking reply.

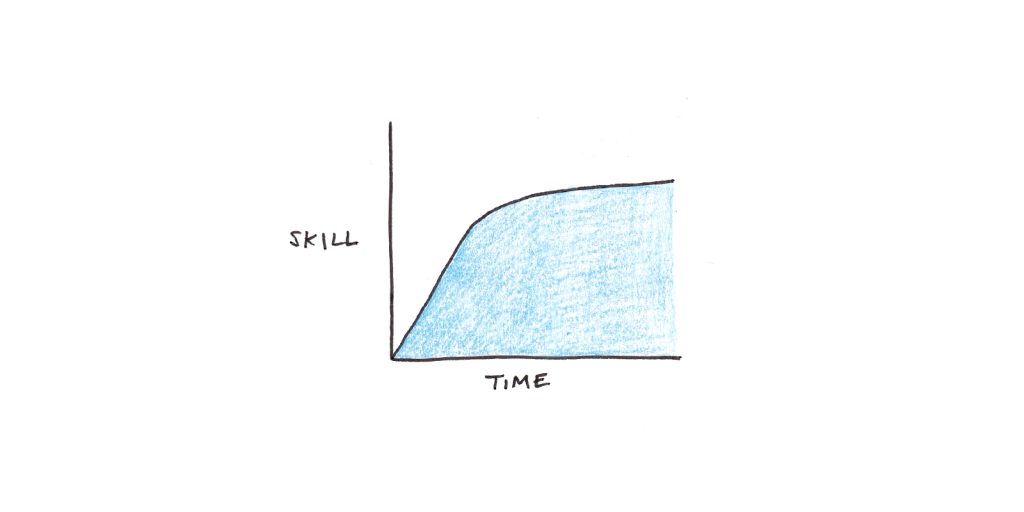

The intermediate plateau contrasts sharply with the beginning phase of immersive language learning. While those early efforts are marked by some intense difficulties, they are also a period of incredible progress. In a narrow window of time, you go from total incompetence to being able to do quite a bit!

In contrast, intermediacy is frustrating. You don’t feel good enough to claim the work of learning is over, but you see diminishing returns from additional study and practice.

The intermediate plateau shows up in almost every field. As a writer for over half my life, I still wish I were better at it. And yet it’s hard to tell whether my efforts are paying off in terms of better prose. Programmers, managers, architects and doctors all have to deal with the difficulty of being neither a beginner nor the best.

Three Theories for Why We Get Stuck

I’d like to review three explanations for what causes the intermediate plateau, each having some relevance depending on the skills. Those are:

- Knowledge grows exponentially with the level of expertise.

- Progress comes to rely more on unlearning than new learning.

- Creative problem-solving overtakes (and is harder than!) imitating others.

The Exponential Explosion of Knowledge

One explanation for the intermediate plateau is that skill building is based on knowledge, and knowledge grows exponentially as you progress in a discipline.

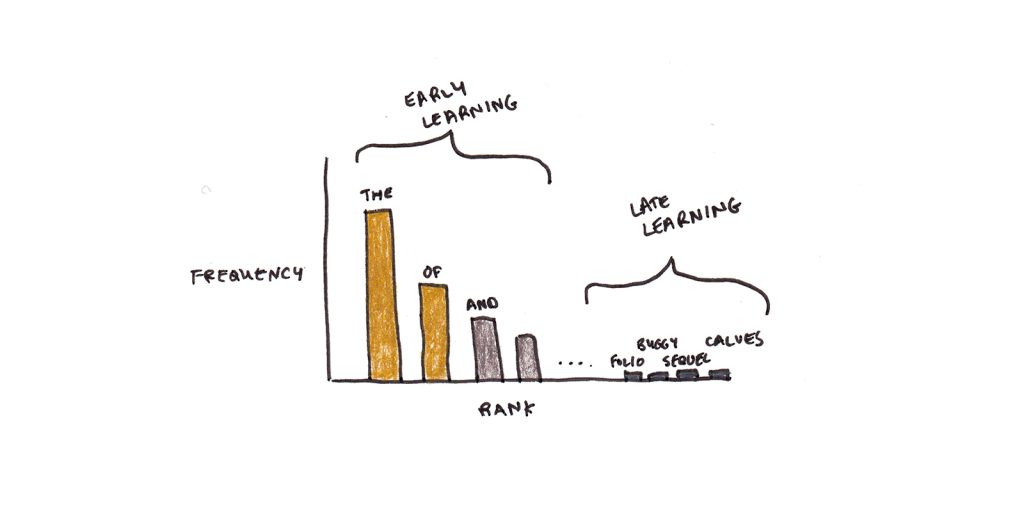

Consider a highly simplified model of language learning, where the only thing that matters are the words you have in your lexicon. According to Zipf’s Law, the usage frequency of a word is roughly proportional to the inverse of its rank in an ordered list of usage frequency.

The most frequently used word in English is “the,” which occurs 7% of the time, about once per 14 words. The second most frequent word is “of,” which occurs 3.5% of the time, about once per 29 words. By this formula, the ten-thousandth most-common word (which apparently is “calves”) would occur roughly 7% x (1 ÷ 10000) = 0.0007% of the time, or about once every 143,000 words.

Each newly learned word takes (roughly) the same amount of mental effort to learn, but the frequency drop-off means that each word contributes less and less to your proficiency.1

In fact, the situation is even worse than this! Knowledge isn’t acquired once and then preserved forever. We often require multiple exposures to learn a word and spaced exposures to sustain it in memory. Because rarer words are used less frequently, they take far longer to become permanent parts of our linguistic repertoire.

Given the rate of forgetting, and the slow accumulation of new words, the intermediate plateau may be the equilibrium point where new learning equals old forgetting. At this level, we forget infrequently-used words as quickly as we learn them, and improvement stops entirely.

Unlearning and Local Maxima

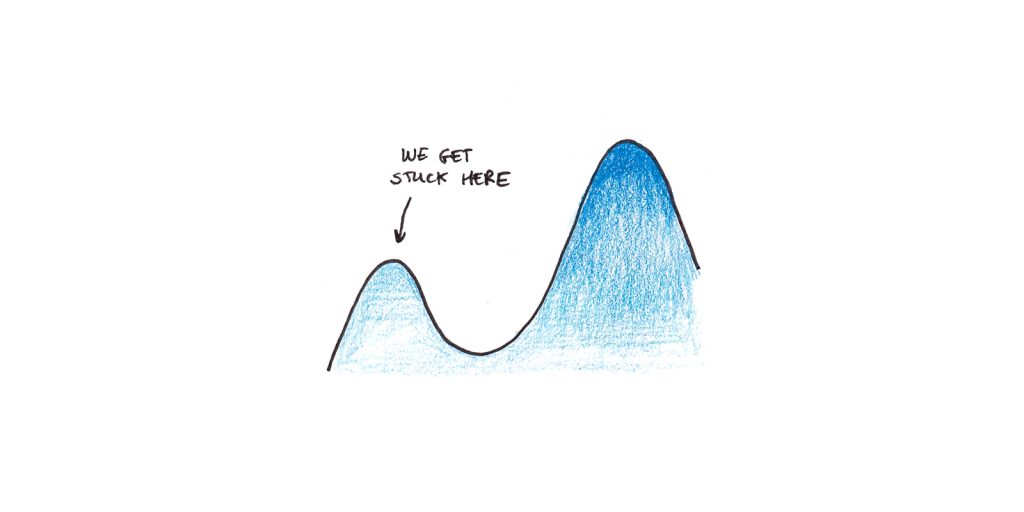

The knowledge-explosion account of the intermediate plateau assumes learning is monotonic. That is, learning is strictly additive—each new word only makes you more proficient, never less.

However, a lot of learning isn’t like this. A person who is learning to type by hunting and pecking on a keyboard further entrenches that method every time they use it. It won’t spontaneously evolve into touch typing, regardless of how much they practice. Similarly, pronunciation often “fossilizes” in language learning, likely because a “good enough” articulation of the language’s phonemes becomes ingrained through repetitive practice and becomes automatic. This makes you more fluent, but it means shaking off a bad accent is even harder than learning new words!

In this account of the intermediate plateau, our lack of progress is due to getting ever-more proficient in mediocre methods. Progress requires interrupting this natural process, fine-tuning our performance, and then rebuilding automaticity on the parts.

The Copying-Creating Barrier

A third reason we get stuck in our progress is that humans are excellent imitators and only lackluster problem-solvers. Crows can figure out how to extract food from a bottle by improvising a metal hook, but only 10% of fifth-graders can do the same.

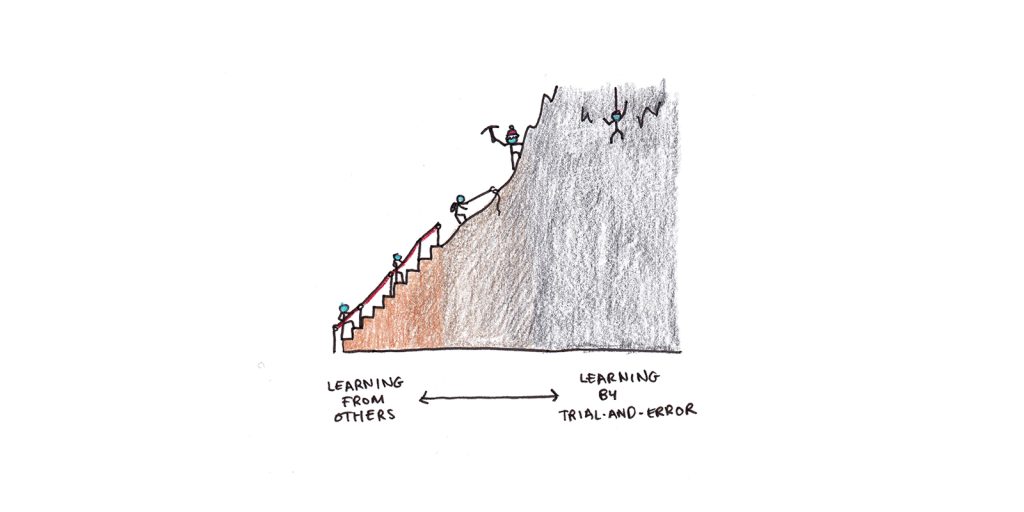

Anthropologist Joseph Heinrich argues that our capacity to imitate—if one person solves a problem, everyone else can copy their solution—is what truly separates us from other species, not our innate problem-solving abilities. Our ability to stand on the shoulders of the countless generations that have come before us is what enables us to make progress.

Unfortunately, this means there’s a sharp distinction between mastering an old trick and inventing a new one. Learning from others is fast, but it is limited to situations that are routine or allow the easy application of an old principle. New circumstances, in contrast, require an extensive problem-solving search in order to make progress.

The intermediate plateau, by this account, can also be a switch from learning from others, to learning by trial-and-error, with the latter being much slower and more painstaking.

How Can You Move Beyond Intermediacy?

Each of the three theories suggests a different potential escape route:

- Exponential knowledge requires exponential effort.

- Unlearning requires deliberate practice.

- Expert mentorship nurtures creativity.

Exponential Effort for Exponentially Growing Knowledge

The unfortunate fact of mastering a language is that, after gaining basic fluency, further learning requires a disproportionate step-up in effort. The only way to overcome the dwindling usefulness of new vocabulary and the regular atrophy of forgetting is to spend more time in practice. That said, I do suspect there are more efficient ways to do this than simply using the language a lot.

Wordsmiths in a non-native language tend to love collecting new words for their lexicon. I suspect the desire to look words up in the dictionary and memorize their meanings is a trait that leads to better performance than someone who only acquires vocabulary when they have to.

Similarly, reading more advanced literature or attending challenging classes can push one into the frontier of seldom-used words and will increase the the usage frequency of the specialized words. Unfortunately, this also increases cognitive load since comprehensibility declines as you delve deeper into the new vocabulary.

Ultimately, it’s probably a mixture of comprehensible input, which ensures fluency and low-effort practice, and more challenging reading or conversations with easy access to definitions/explanations that will matter.

Unlearning Requires Deliberate Practice

Unlearning to progress in skill development was a theory favored by Anders Ericsson. Building on Fitts and Posner’s influential three-stage model of skill development, he argued that automaticity was a major barrier to improvement.

Fitts and Posner’s model of skill acquisition has three stages:

- Cognitive – When you learn the basics of a skill and understand how it works.

- Associative – When you begin practicing, combining the parts of a skill into larger chunks and weeding out significant mistakes.

- Autonomous – As errors decline, you perform the skill with less and less conscious effort.

The “deliberate” part of deliberate practice refers to both the need for practice sessions outside of work and play, and the mental effort needed to bring the skill out of the automatic state and back to the cognitive/associative state where deliberate effort can be applied.

Essentially, we’re not trying to add to our knowledge so much as weed inefficiencies from our well-learned routines.

Creativity is Enhanced By Expert Mentorship

In problem-solving, we can get further if we see better ways of doing things. Sometimes we get stuck on the intermediate plateau because we have learned everything we can from those around us, and now improvement depends on our own inventiveness. The people who succeed are often those who can find better mentors and, therefore, can continue the relatively efficient learning-from-others path.

Support for the importance of expert mentorship can be seen in the history of scientific accomplishments. Harriet Zuckerman famously analyzed the path of American Nobel laureates. She found that a significant proportion of those who won a Nobel prize were mentored by someone who also won it. Interestingly, most won the prize before their mentor did, so the role of mentorship seems to be much more than just institutional prestige.

Mentorship needn’t be an official relationship. Even having a knowledgeable peer network can help. The more you can learn from others, rather than having to invent on your own, the faster you will progress. Those who are isolated from the help of other people will hit the problem-solving barrier earlier, and thus their progress will slow.

Is Mastery Worth It?

Whether it’s extensive (and time-consuming) knowledge acquisition, effortful deliberate practice, or seeking access to elite guidance, mastery doesn’t come easily. In some cases, it’s worth wondering whether it’s necessary.

Despite my focus on learning, I’m firmly in the intermediate camp for all of the skills I’ve spent time on. Intermediacy is nothing to be ashamed of. For many skills, there’s a lot you can do with being “good enough” rather than world-class.

Still, if going beyond your current level is necessary, it’s helpful to think in terms of what is required to get the job done.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.