I was recently a guest on a podcast where the host asked why people are less interested in learning as they get older.

While there are certainly exceptions, the observation seems valid. Nearly all formal schooling is concentrated in our childhood and early adulthood. Stories of people going back to school in their twilight years are newsworthy precisely because this is rare.

It also fits with my informal observation that people are much more reluctant to pick up new skills or topics as they get older. I learned to downhill ski at thirty, but I only personally know a few people who began much older than I was.

This is a worrying trend. Learning is an integral part of the good life, so if forces make it harder (or less desirable) to learn, it seems like it would be helpful to understand them. Let’s consider three theories, and see what they suggest we can do about defying the trend.

Theory #1: Opportunity Costs and Investment Horizons

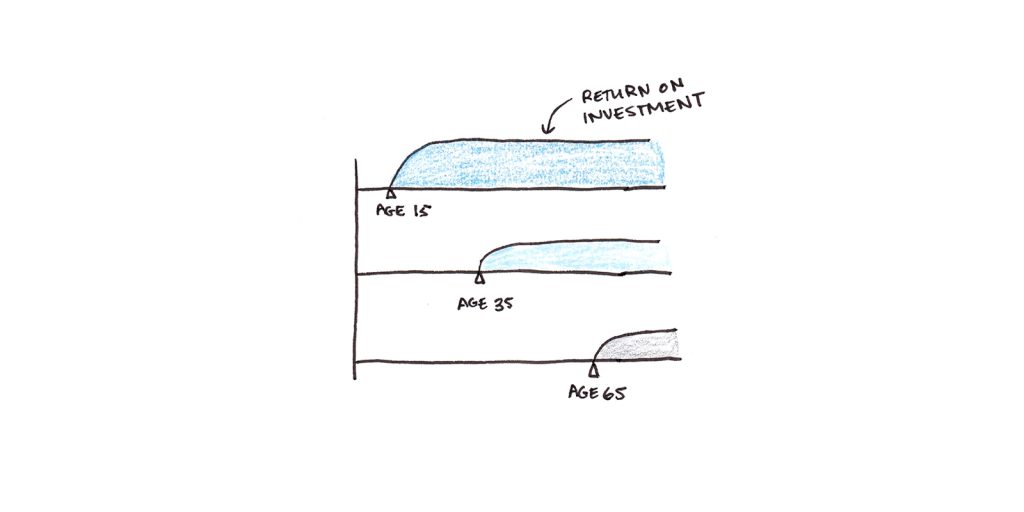

The first explanation is economic: learning is an investment. As you invest in some skills, but not others, you get a greater return from activities where you have considerable training. Thus, your opportunity cost for learning new things increases. Therefore, a failure to learn new things is perfectly rational, even if it can result in inflexibility as we get older.

One way this manifests is the time horizon you have to recoup an investment. A twenty-year-old presumably has forty years for a career to earn back an arduous training period. A fifty-year-old only has ten. Therefore, younger people should be able to make longer, riskier investments than those who need them to pay off quickly.

Another way this can occur is if investment in one skill makes time spent on new skills comparatively less attractive. If I have zero knowledge of programming and accounting but equal potential ability, then the two are roughly the same for me. In contrast, if I have a decade of programming experience, then an hour spent programming will be much more valuable than an hour spent learning accounting. The economy incentivizes specialization, even if we’d prefer to be more well-rounded.

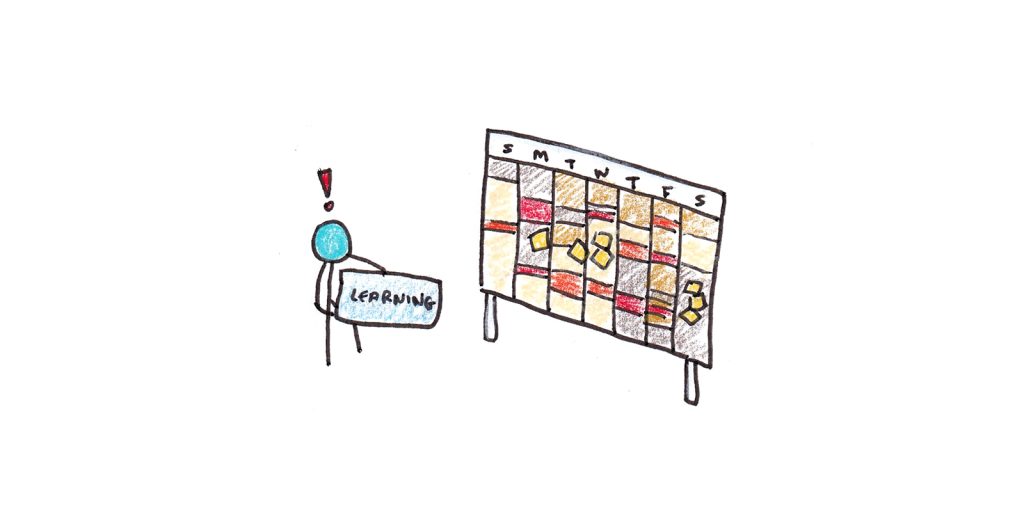

Theory #2: We’re Too Busy

Another explanation for dwindling curiosity is that life gets busier as you get older. I feel this acutely today. When I compare my schedule now, with a toddler at home and a business that employs multiple people, I feel far more time-constrained than when I was in my twenties.

Learning new things takes time. While efficiency can help, the time cost for even well-designed learning may be prohibitive for busy professionals with kids.

Energy may matter even more than time. If you work full-time at a mentally-demanding job and have responsibilities at home, you may not have the energy needed to invest in a cognitively-demanding project. Binge-watching Netflix may not be where you’d ideally like to spend your time, but it makes sense if you feel chronically exhausted.

This also helps explain why there can be a sudden urge to learn after retirement. With kids gone and work stopping, people finally have the time to engage in learning projects they were sidelining during their career.

Theory #3: Older Minds Can’t Learn as Well

The most popular explanation I hear for declining education is that when you’re older, your brain simply can’t absorb new information as quickly.

There is a grain of truth to this. Fluid intelligence peaks in your early twenties and declines afterward. However, the decline is gradual and minimal. The research I’ve seen seems to indicate that it’s only a serious problem in advanced age. Even then, there is high variance, with some people becoming senile and others experiencing few issues.

That said, age is often an advantage to learning. Older people are usually more responsible and organized, which assists in sticking to a project. Also, accumulated knowledge can make learning easier. Your past experience can be a huge benefit when delving deeper into subjects you’ve previously studied or related fields.

Overall, I’m less convinced that age per se is a significant factor, even though it is oft-cited.

How Can We Sustain Learning Lifelong?

Given the possible theories, I think there are a few things we can do to continue learning:

- Reduce the effort for learning. Always carry a book with you. Set up your environment so learning projects can start and stop on demand. Pick projects that overlap with career, social or parenting goals so you can justify the time investment.

- Set aside time for experiments. Straightforward calculus suggests that doing what you’re already good at has the best payoff. But you won’t encounter nearly as many opportunities if you never learn anything new. Setting aside time for hobbies you’re bad at, books you know nothing about or skills you’ve never practiced may seem wasteful, but it’s a good practice to avoid getting stuck in a rut.

- Shift your focus away from skills that involve quick wits to those that rely on accumulated knowledge. The decline in fluid intelligence is overrated as an explainer for learning difficulties. And also, there’s a reason why groundbreaking mathematicians skew younger than historians. Shifting to knowledge-intensive subjects seems like an overall sound strategy.

Above all, however, I think losing interest in learning is a choice. For every trend, there are exceptions. With the right attitude, you can be one of them.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.