If you’ve been following productivity advice for any length of time, you’ve probably experienced the following cycle:

- You find a new tool, system or motivational slogan.

- You get excited, work hard and get far more done than usual, seemingly proving that the new thing works.

- A few weeks pass, the new thing becomes old and you lose enthusiasm.

- Eventually, you revert to your old habits.

Why is productivity so difficult to sustain?

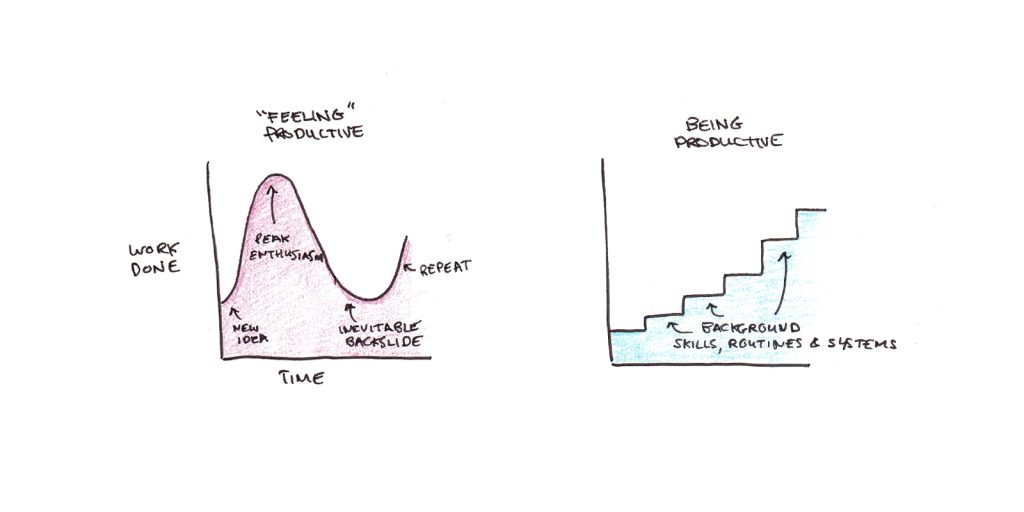

I suspect a major cause of the difficulty is that we readily conflate two different ideas of what it means to “be productive.”

The first is a subjective feeling of productivity. This comes when we’re super busy or exerting extra willpower to focus on our work. This feeling is easy to tap into when you’re motivated by a deadline or a new productivity device.

The second is the objective output of productivity. This is the actual amount of important work that gets done. Books read, code written, clients served or products shipped.

In the short term, the subjective and objective views of productivity often coincide. It usually is the case that when we’re subjectively productive, more work is actually getting done.

However, in the big picture, subjective and objective views of productivity often have nothing to do with each other. One author might leisurely write ten books over a decade, while another fails to turn in a manuscript despite ardent effort. The top researchers, programmers and entrepreneurs have more professional impact—by orders of magnitude—than their typical peers, but it’s usually not just because they’re just trying really hard.

Sustainable Productivity is Invisible Productivity

Sustainable productivity comes from decoupling the short-term feeling of being busy or exerting effort from the long-term investments that allow you to get more work done whether or not you “feel” particularly productive.

Sustainable productivity comes from a few sources:

- Low-effort routines or habits. The things you do without thinking about them, not just on your best days, but on your laziest days.

- Knowledge and skills. Whether something is a vexing problem or a trivial task depends on the skills and experience you’ve accumulated.

- Eliminated work and tasks. If tasks can be automated, delegated, deleted or streamlined, removing needless steps or tasks will have a far greater impact than simply trying to do them faster. Doing more important tasks means doing fewer unimportant ones.

But most important is recognizing that in order to become more productive, you have to worry less about feeling productive and more about creating systems that allow you to get more done—without herculean effort.

Next week, Cal Newport and I are opening a new session of our popular program, Life of Focus. There, we’ll guide students in building a foundation for their own sustainable productivity systems and practices. We hope you’ll join us!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.