One of the few lessons I recall from business school is the make-or-buy decision. Big companies often face a choice: should they make something in-house, or outsource it to a supplier?

The decision depends on many factors, but a big part is cost: will it be cheaper or more reliable if you invest in in-house production? Or does it make more sense to pay someone else to do it?

Decisions about whether or not to learn something are often similar. For almost any conceivable skill you can:

- Learn to do it yourself.

- Hire someone else to do it.

- Avoid doing it entirely.

Consider programming. You could learn to write code, hire a programmer to do it for you, or choose work and projects that don’t require you to create software.

Or language learning. You could learn to speak Mandarin, hire a translator, or avoid doing business with monolingual Mandarin speakers.

The same choice applies to countless other skills, from understanding the tax code to applying medical advice, repairing drywall or planting a garden. You can learn, outsource or avoid.

Learning Rarely Makes Sense Short-Term

One common feature of this problem is that the costs of learning rarely make sense if you’re only thinking about immediate benefits. Even if you’re the smartest person on earth, hiring a Mandarin translator, Java programmer or car mechanic to deal with your problem still takes less time and energy than learning to solve it yourself from scratch.

Yet, if you already know how to solve a problem, doing it yourself is often (but not always) the most effective option. Hiring people takes time, increases the possibility they won’t understand or be able to deliver what you want and can be more expensive.

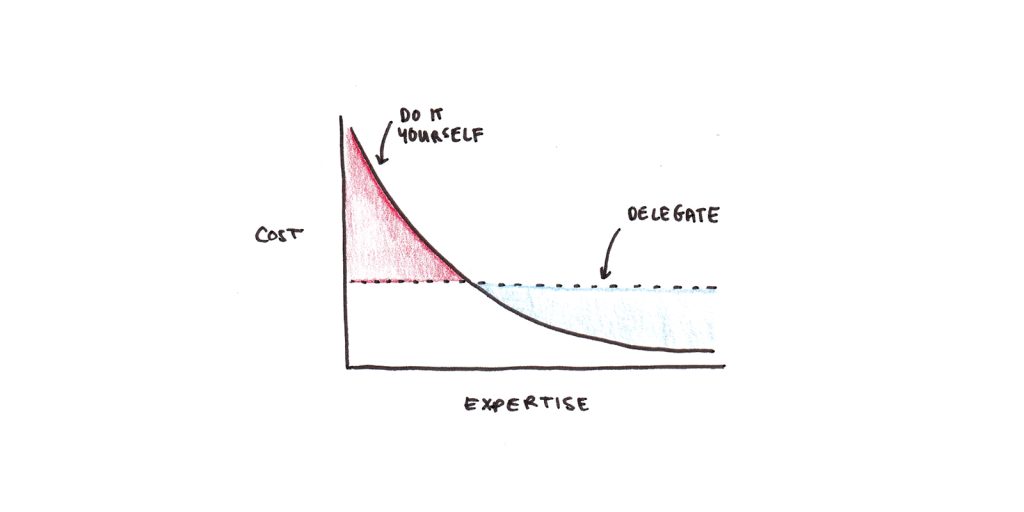

Viewed this way, the optimal point for many learn-or-delegate decisions depends on your prior expertise:

This analysis suggests you should do what you’re good at, and delegate what you’re not.

The major wrinkle in this approach is that your level of expertise isn’t constant. It varies depending on the amount of practice you’ve had on the problem. One of the most famous empirical results is the power law of practice, suggesting that many aspects of proficiency follow a roughly power-law relationship with the amount of practice.

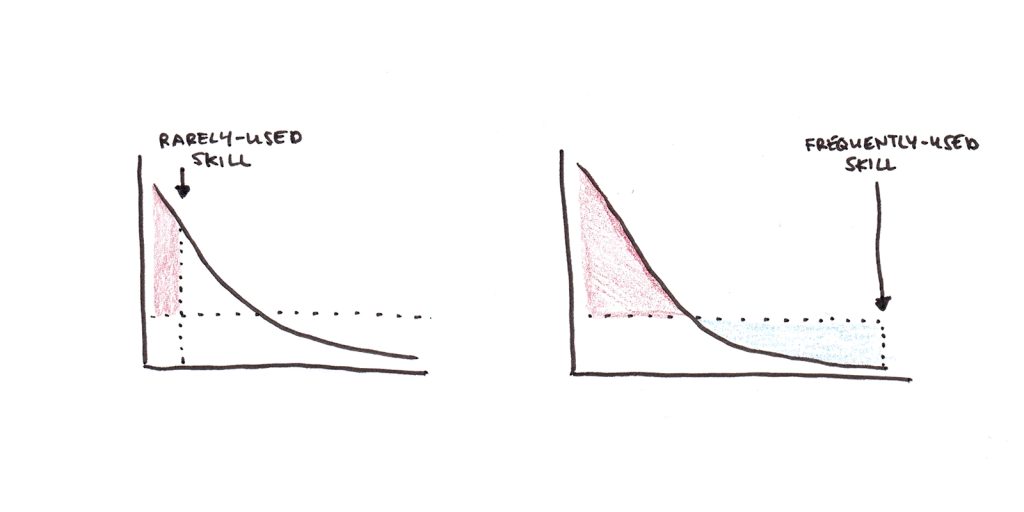

The answer to the learn-or-delegate decision doesn’t depend only on your current level of expertise, but also on how often you expect to perform the skill. If you’re currently below the competency threshold where doing it yourself makes sense but will probably use the skill a lot, the total lifetime cost of learning may end up being less than delegating:

While I’m using an economic lens here, the reasoning still applies outside your job. How much I enjoy painting as a hobby depends on how good I feel I am at it. Thus there’s often an implicit learn-or-ignore decision with recreational activities that follows the same trade-off.

Do We Underinvest in Learning?

To summarize, many decisions about learning have the following features:

- Doing it yourself doesn’t initially pass a cost-benefit test.

- The more you practice, the lower the cost becomes.

- Thus whether it’s “worth it” to learn something depends on a far-sighted calculation of how much you’ll need to use the skill.

Unfortunately our intrinsic motivational system is remarkably short-term in its focus. Immediate costs or payoffs influence our decision far more than long-term ones. Experiments show people often pay steep discount rates for delayed rewards, in ways that are inconsistent with any rational agent (even an extremely impulsive one).

This suggests we may be underinvesting in learning. We’re disinclined to practice skills that fail an initial cost-benefit analysis—even if our investment of practice would be profitable over the course of our lifetime.

This insight helped Vat and me while learning other languages. The costs of practicing a language are relatively high when you’re not consistently using it. In the short term, forcing yourself to interact in a new language is also costly. But, if you practice enough, speaking the language of the country you’re visiting becomes easier than sticking entirely within an English bubble. Adults are resourceful and frequently find ways to avoid using an unfamiliar language; the consequence is that few get anything close to the levels of exposure that young children can’t help but get when learning.

Matthew Effects in Learning

Another consequence of this basic model is that we should expect Matthew Effects in learning.

The Matthew Effect was first coined by sociologists Robert Merton and Harriet Zuckerman in their study of elite scientists. Eminent scientists often get more credit than unknown researchers for similar work, meaning that, over time, eminence tends to compound while less famous academics linger in obscurity.1

Later, psychologist Keith Stanovich applied the same insight to reading. Those with a slight advantage in early reading ability had a slightly reduced cost of reading new material. This lead to them practicing more, further reducing the costs of reading. Given the connection between reading and other forms of learning, he even hypothesized that early reading ability might bootstrap intelligence by making it easier to acquire new skills and knowledge.

Research bears out Stanovich’s hypothesis. In a study looking at identical twins who varied in early reading ability, the slightly more proficient twin later showed gains in intelligence compared with their genetically-identical sibling. Skills beget skills; knowledge begets knowledge.

Specialization and Focusing on Strengths

At this point, it’s helpful to clarify. I’m not suggesting that since learned skills get easier with practice, we should do everything for ourselves and never delegate.

This is false, even by the basic logic I’ve spelled out above. Some tasks simply aren’t encountered frequently enough to cross the cost/benefit threshold. I may never have an opportunity to speak Mongolian, so if I ever meet a monolingual Mongolian speaker, I’d be happy to lean on Google Translate.

Additionally, we can’t consider skills in isolation. Spending time learning one thing is an implicit decision not to learn something else. I could learn French, but that time is taken away from learning Mandarin. I could learn Javascript, but that time can’t also be spent learning Python.

Ultimately, specialization, not self-sufficiency, is the road to abundance in the world we live in today. We delegate the vast majority of skills in our lives, not because learning them all is impossible, but because getting really good at one thing makes sense when it’s relatively easy to delegate everything else.

Despite spending years learning programming, I do virtually none of it for my own business. Given that my writing is central to my business, and I don’t have enough time to do all the writing I’d like, hiring other people to do the programming makes more sense. Those people, in turn, tend to be much further along the expertise curve than I am because they’ve made a similar decision to specialize.

That being said, there are many instances where skills can’t easily be delegated. I might be able to hire out behind-the-scenes programming for my website, but it doesn’t save effort or cost to hire someone to read the research used to write the articles. If I don’t understand the research, I can’t weave it into the text I’m producing.

In other cases, delegation is an imperfect or inconvenient substitute for being able to do something yourself. Relying on a translator is not equivalent to being able to speak the language yourself when you move to another country. Being able to read a text isn’t made redundant if someone narrates it to you aloud. Thus being able to speak the language of the country you live in and being able to read are skills that are almost certainly worth mastering.

Thinking about Learning in the Long-Term

I find it useful to keep in mind a few things when I face resistance to learning something new:

1. How much can I expect this skill to get easier with more practice?

One way to estimate this is to look at people with varying degrees of experience. How much effort did it take them to do what you struggle with? The learning curve is quite steep for some skills—you get good relatively quickly. For others, the curve is flat for a long time—you may need to practice for years before you feel it’s worth the effort.

2. How much would I use the skill if I was better at it?

Supposing you could reach the relatively flat part of the practice curve, how much would you use it?

If you live in a country that speaks a language you don’t know, learning that language would definitely pass the cost-benefit test. Learning a major world language you might use in work or educational contexts probably also does. A niche language that isn’t spoken much … maybe not? In this case, it may only be worth learning if you have a strong intrinsic motivation to learn it.

If a skill is central to your career, it may easily be worth the cost, even if it is initially difficult for you to learn. In contrast, a career skill that doesn’t fit well with your existing skills may go unused even if you’re nearly an expert—it’s simply cheaper to outsource.

3. How much would I enjoy the skill, conditional on being better at it?

Economic rewards aren’t the only motivation. If you’re good at something, you tend to enjoy it more and draw personal satisfaction. But that’s more true of some skills than others. You might be particularly proud of being able to paint a realistic landscape but not feel too special about being able to file your taxes quickly.

Deciding when it makes sense to learn isn’t trivial, but given that our intuitions often give us a misleadingly short-term picture of what’s possible, it can be helpful to think more deeply about it.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.