In my recent call for questions, a reader asked me a version of Peter Thiel’s now-famous interview question: what important truth do few people agree with you on?

I had a hard time answering this because, for the most part, I’m an intellectual conformist. I read what experts think and generally agree with their consensus.

While intellectual conformity may sound cowardly, I’d argue it’s actually a kind of virtue. My professional incentives align with being contrarian rather than dryly repeating whatever Wikipedia says on a topic.

I usually agree with experts because experts are regular people who have learned a lot about a topic. If regular people tend to coalesce around a certain worldview after hearing all the evidence, it’s probably because that worldview is more likely to be correct!1

A side-effect of this habit is that conforming to experts’ thinking sometimes puts you wildly out of step with most other people.

Non-expert opinions often sharply diverge from how experts see a subject. So when you read a lot about a topic, and your opinion converges with the typical expert view, it can diverge from the commonsense view of reality.2

Consider the idea that the mind is a kind of computer.

This is the central assumption of cognitive science and represents an orthodox view within psychology and neuroscience. There are caveats and dissenters, to be sure. Still, faith in the information-processing paradigm of the mind is far more prevalent among people who spend their entire lives studying it than the average person on the street.

Why the Mind is a Kind of Computer

The classic rhetorical trick amongst skeptics of this view is to point out the history of analogies for the brain. The ancient Greeks saw the mind as a chariot pulled by horses of reason and emotion. René Descartes viewed the brain as a system of hydraulics. Every age, it is argued, has fumbled for the best metaphor for the brain and ours is no different. Just as the idea that pressurized fluids manage the brain seems silly today, so will a future era see the computer analogy as quaint.

But there is good reason to think the computer analogy is different.

This is not because brains are literally similar to a laptop. Instead, it is because computer science has discovered that computation is a relatively abstract property, and many completely different physical devices share the same constraints and powers.

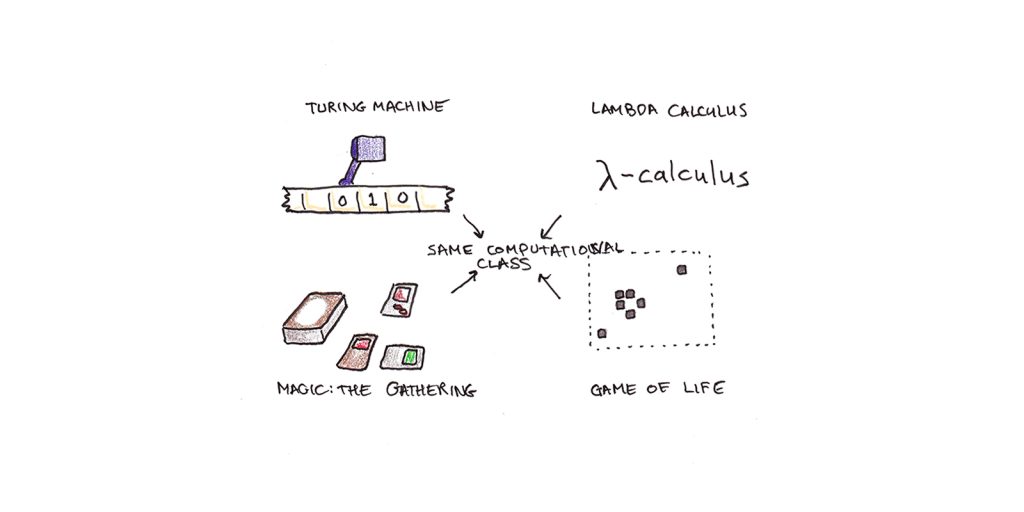

Alan Turing and Alonzo Church each independently discovered that the former’s Turing Machine, a hypothetical instrument that followed instructions on an infinite ticker tape, and the latter’s Lambda Calculus, a mathematical language, were formally equivalent. Since then, many seemingly unrelated systems have been proved formally equivalent—from Conway’s Game of Life to the Magic: The Gathering card game.

The extended Church-Turing thesis argues that this isn’t a coincidence. Any physical device, whether a brain, laptop or quantum computer, broadly has the same powers and constraints.3

Saying computers are “just a metaphor” for the mind is misleading because it restricts computers to the Von Neumann architecture used in silicon computers today. But the abstract concept of a physical device that processes information is much broader and more powerful. The heart differs from a bicycle pump, but is obviously a member of the abstract class of “pumping machines.” In the same way, the brain is quite different from a laptop, but they’re both members of the abstract class of “information-processing machines.”

The point isn’t to elide any difference between the digital computers we manufacture and the biological computers we’re born with. Instead, it’s to recognize that if you wanted to understand the heart but were somehow philosophically opposed to thinking of it as a kind of pump, you would have a hard time making sense of how it works.

But What Kind of Computer?

Saying the brain is a kind of computer is like saying bacteria and people are both organisms. The latter is also uncontroversial within biology today, even though the idea would have seemed fantastical two-hundred years ago. At the same time, bacteria and people are different.

Clearly, the brain differs in many ways from the transistor-based computers we are familiar with:

- The brain is far more complicated. The human brain has ~100 billion neurons. Each individual neuron has sophisticated computational properties that can require a supercomputer to model. While a bacteria and a human differ in more than just size, the scale of things is a significant distinction. Bigger is different.

- The brain is massively parallel and interconnected, having as many as a quadrillion synapses. Modern computers have a serial architecture where computation goes through a central processing unit.4 In contrast, brains distribute the calculations across the entire neural network. This difference changes the algorithms that can be used, which is why human thinking is qualitatively different from computer code.

- Bodies have sensory inputs and motor outputs that interact with our environment. The human brain has billions of sensory cells and billions of motor effectors, each of which engages in feedback loops with the environment. This is a major contrast with most human-built computer systems which are essentially detached from the world except for small windows of input and output.

These differences aren’t trivial. But, just as a single bacterium and a human being are both organisms, I think it’s worth stressing that even these great differences don’t alter the fundamental truth that the mind is a type of computer.

What About Meaning, Emotions and Subjectivity?

Within psychology and neuroscience, the dominant controversies are over what kind of computer the mind is rather than whether or not it computes. But I think the more typical objection to this viewpoint from people outside those fields is a humanistic one. Essentially, the objections are:

- Computers are logical; humans are emotional. The cognitive scientist would counter that emotions are a kind of computation. Motivation, attention, fear, happiness and curiosity are all important functional properties. While the nature of the algorithm isn’t transparent to us via introspection, this is broadly true of all of our cognitive processes.

- Computers aren’t sentient; humans have consciousness. I agree with Daniel Dennett that philosophical ideas like qualia, p-zombies or the impossibility of knowing what it is like to be a bat are misleading intuitions. The “hard” problem of consciousness-as-subjectivity is a confusion, not a genuine puzzle. In contrast, while the “easy” problem is still unsolved, there’s been considerable headway in explaining how consciousness-as-awareness works.

- Computers are rule-governed; human thinking is holistic. Hubert Dreyfus famously made this argument against the computer analogy back when the serial-computer model was more prevalent in artificial intelligence. However, I think the “what kind of computer?” framework above largely resolves this issue. Presumably, the brain’s sheer quantity of processors and enormous parallel activity explain the powers (and limitations) of intuition and holistic thinking.

- Who are we to think we can “understand” the soul? The final objection is simply an appeal to mysticism. I’m not principally against this—if you’d prefer to dwell in the mystery of life rather than try to figure things out, that’s a reasonable choice. But obviously, it’s the antithesis of the aims of science.

We know less about how the mind works than we know about, say, microbiology. But, just as vitalism was proved false and life really is just chemistry, I’m convinced the mind really is just a computer and that the ongoing scientific project of figuring out how it works is one of the most exciting pursuits of our time.

Footnotes

- There are exceptions, of course. Experts form communities and can become enamored with a way of viewing the world for reasons owing to tradition, theoretical tractability or politics. But, if you aren’t deeply familiar with the arguments and evidence experts use, I believe you’re better off accepting the orthodox worldview. In other words, unless you, too, are an expert, your beliefs will be more accurate if you believe what experts think than if you adopt contrarian positions. The main reason to be a non-expert contrarian is if your personal incentives aren’t aligned with having maximally true beliefs!

- In areas I’m not as well-read, my opinions are likely to be grounded more in common sense than expertise. Nobody is an expert in everything, and I’m no exception.

- I’m being vague here with the words “broadly,” “powers,” and “constraints.” A full explication of what is meant would require a lot of academic computer science.

- GPUs and more recent NPUs do make things more complicated, but the broad design of a computer, where most calculations are performed in a narrow physical space within the overall device, separate from storage, input and output, is still the case.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.