In the previous two lessons, I shared why you should pay attention to successful people’s career capital rather than their personal quirks when trying to emulate their achievements. Next, I applied the economic model of supply and demand to understand why some people are able to negotiate great career perks—money, autonomy, flexibility—while others are not.

Career capital, particularly rare and valuable skills, is the starting point for finding work you love. But how do you get them?

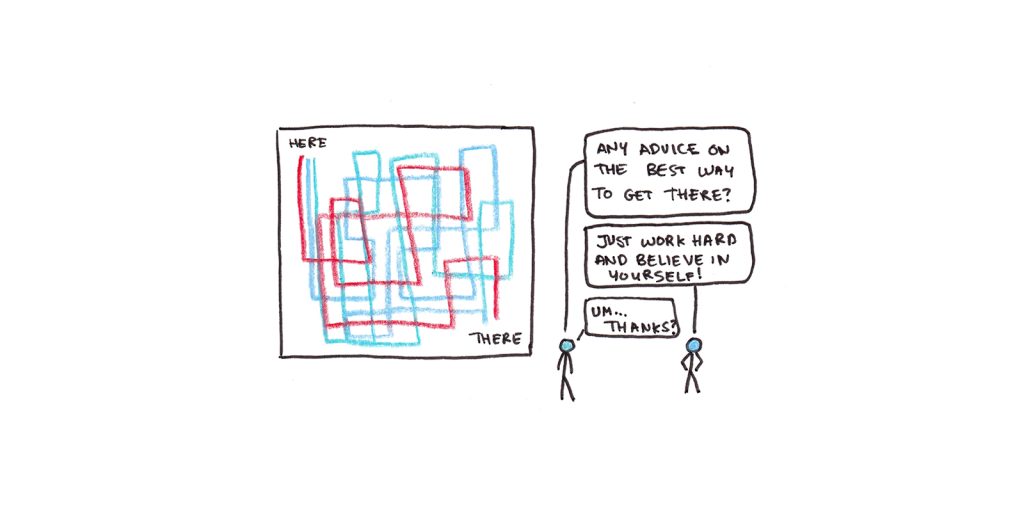

A tempting answer is simply to work hard. While it’s true that success requires hard work and most successful people tend to be hard workers, working hard does not guarantee success.

While it’s nearly impossible to build rare and valuable skills without hard work, tons of people work hard but still don’t have great career capital. As a result, despite their great work ethic, they don’t get the same perks that true top performers do.

Cal and My First Lesson from 8+ Years of Top Performer

You avoid this trap by building skills that result in useful career capital, so the nuts and bolts of how to build these skills were on Cal Newport’s and my mind as we began working on the first iterations of our course, Top Performer.

We already had an idea about how people build skills—Anders Ericsson, the psychologist who pioneered the concept of deliberate practice, spent decades studying the mental efforts needed to master difficult skills. Focused practice sessions, particularly under the supervision of a coach, can make all the difference in whether your skills will grow or stagnate.

However, when we ran our first sessions for the course, we noticed something different: Most people had no idea which skills they needed to build!

Worse, many people seemed to gravitate towards skills tangential to what really would make a difference. People seemed keen to improve skills that were fun to work on—an effortful project (but not too hard) so they could feel they were doing something to improve, but they weren’t working on what mattered most.

There’s nothing wrong with learning things for fun. But this approach can be counterproductive if your aim is to build career capital. You can spend months improving a skill that isn’t directly related to what employers, clients or customers really want.

There are No Short-Cuts, But Plenty of Dead-Ends

Realizing that many people were heading down dead-ends with their deliberate practice efforts, Cal and I adjusted our next iteration of the course: Before getting into intensive skill-building work, we had the students research how their career path actually worked. Once they understood this, they better understood which projects would move them in the right direction—and which ones were a waste of time.

Doing this kind of research is tricky. Most of what you need to know is too specific to be written down in a book or article, so a trip to the library or a web search often comes up short. Instead, you need to talk to people. Yet talking to people who’ve achieved success can be equally frustrating! Even people who have amassed a surprisingly specific set of skills often shrink back to generic platitudes about the value of hard work when asked how they did it.

However, doing this research properly is essential. Knowing the path before you start walking it helps you avoid common traps people fall into when building their career:

- Getting a master’s degree that nobody cares about.

- Working on technical skills when you need people skills.

- Not finding the right way to present your skills on your resume.

- Not recognizing which jobs are career-building opportunities and which are dead-ends.

After working with many students over the years, Cal and I found that the best people to talk to for this advice are 2 to 3 steps ahead of you in the career direction you’re considering. These people have recently moved up, so their information is up-to-date and fresh in their mind.

Once you find and contact these people, you need to get them to tell you how they got where they are—which is surprisingly diffcult. Early on, Cal and I found that our students were simply asking those people for advice. While this seems like the obvious move, it almost never works. Instead of asking directly, you need to act like a journalist covering the story of this person’s career transition—figure out the where, when, what and why of how they made the career leap you’re currently contemplating.

These two actions, finding people 2 or 3 steps ahead of you in your career and interviewing them to figure out exactly what they did (not just the advice they want to share), help you narrow down which elements of your career capital you need to invest in and which you can ignore going forward.

In the next and final lesson, I’ll share my thoughts on moving beyond identifying valuable skills to actually getting good at them. After that, Cal and I will be opening Top Performer for a new session. If the ideas I’ve been sharing have resonated with you, I think you’ll enjoy the full course where we put them into practice.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.