A core belief of mine is that (almost) anyone can learn (almost) anything, provided they go about it the right way.

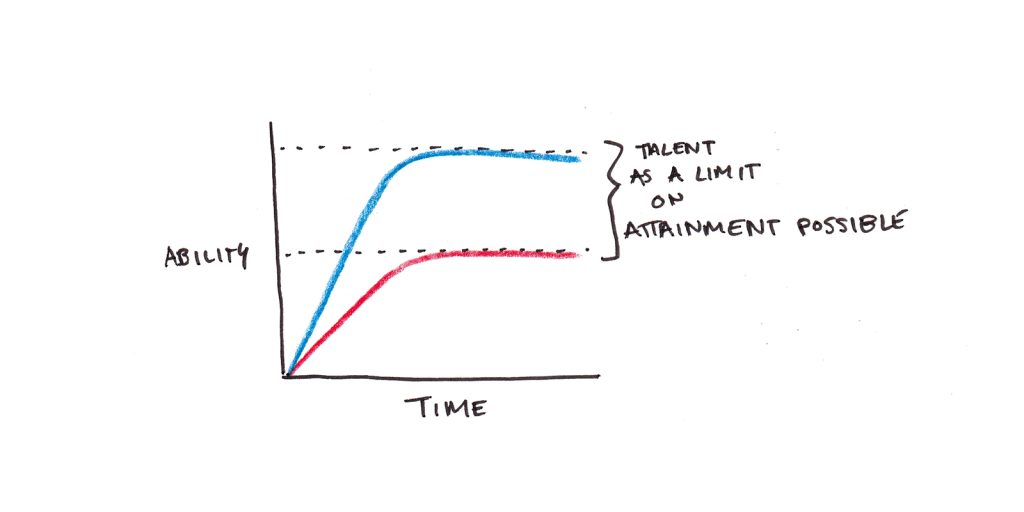

Surprisingly, this is not a widespread belief. Instead, I think most people tacitly believe that some skills or subjects are simply beyond their mental abilities to learn. Maybe they’re “not a math person.” Perhaps they aren’t linguistically talented, musical, artistic or athletic. In short, people have a view of themselves like this:

I’m not here to deny talent or intelligence. Some people will learn things faster and more easily than others.

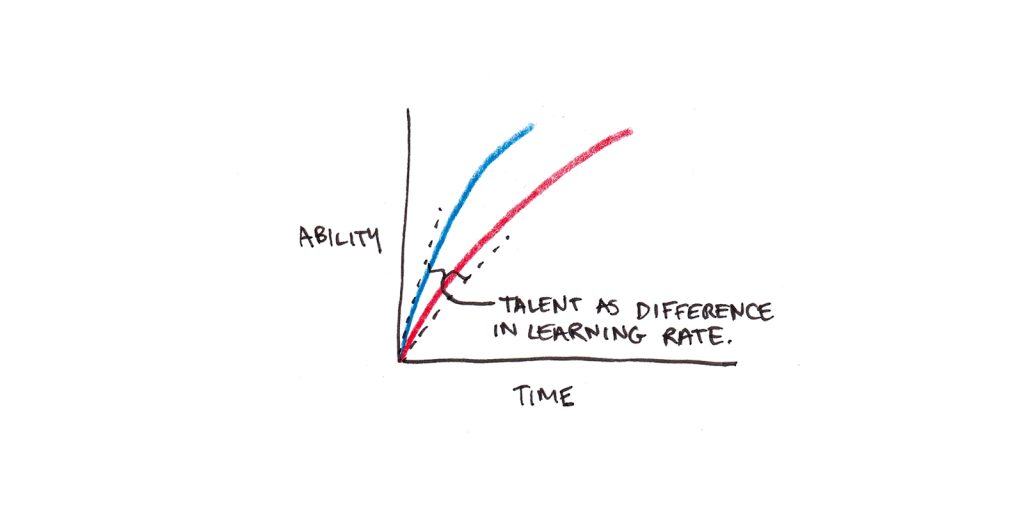

But I concur with psychologist John Carroll who argued that the difference between students isn’t in their potential to learn particular things, but in how fast they can learn them. In short, some people learn quickly, and some people learn more slowly, but they could all reach the same destination if given the proper support:

Why I Believe in Universal Learnability

This belief of mine isn’t just a feel-good tenet of faith. There’s strong evidence that talent impacts learning rate, not eventual attainment:

1. The strong impact of prior knowledge on skills.

One of the best predictors of learning achievement is prior knowledge of the subject. This makes sense—if you know more, you have less new material to learn, and you’re better able to understand and integrate new knowledge.

In a famous experiment, researchers gave students a text narrating a baseball game and tested them to see how much of it they could remember. The authors found that reading ability didn’t matter so much, but knowledge of baseball did. Indeed, subjects who were poor readers (a kind of proxy for lower general aptitude) but had a lot of baseball knowledge did better than good readers without it.

Some psychologists have argued that all acquired abilities are really knowledge in disguise. This theory seems more plausible if we expand the definition of knowledge to include procedural skills and implicit beliefs, not just book knowledge.

If it is true that most of our cognitive abilities are grounded in acquired knowledge, the argument for a skill or subject not being learnable is, essentially, an argument that certain kinds of knowledge fundamentally aren’t learnable for some people.

2. Working memory load changes in response to changes in expertise.

A well-documented finding is that fluid intelligence, the ability to reason and think flexibly, is closely correlated with working memory capacity. While the exact relationship between the two is still debated, one explanation for the tight link is that greater working memory capacity facilitates intelligence by allowing one to hold more things in mind simultaneously.

Another finding from the research on expertise is that experts can hold more information at one time than novices. This appears to be a specific skill associated with training, rather than a transformation of their general capacity. Theories of how experts are able to do this vary—chunking theories argue that experts manage to compress information into elaborate patterns, and retrieval cue theories argue that experts use long-term memory storage to keep track of the task. Perhaps both are correct.

This means that, in subjects where you have sufficient experience and training, you’re effectively much smarter.

3. “Universal” skills are culturally specific and vary in time.

In the Middle Ages, literacy was a rare talent reserved for a priestly caste. If you lived then, there would likely be an assumption that reading was something most people couldn’t learn. Yet today, literacy is near-universal.

Which skills and subjects are considered learnable is primarily a function of their importance in society. Most people learn to read because reading is central to functioning in our society, so we give adequate time and training to budding readers. In contrast, learning to hunt, to name flora and fauna, or to speak multiple languages are skills previous societies regularly mastered that we don’t broadly emphasize today.

Of course, within a given culture, some people will be better readers, hunters or language learners than others. Some will find it easier, and some will find it harder.

My point is that there is much more variance between different cultures than within a single culture when it comes to which abilities are considered “universal.” This is consistent with the idea that nearly anything is potentially learnable by the vast majority of people, if it is given sufficient priority.

Why Do We Feel Some Things Are Impossible to Learn?

If almost everything is potentially learnable by nearly anyone, why does it not feel this way?

I suspect there are a few common reasons that make learning harder than it needs to be:

1. We judge relative proficiency, not absolute potential.

Again, I believe that talent and prior experience drive our learning rate more than our learning potential. But we mostly measure rate of acquisition, not ultimate attainment, in schools. Because of this, we end up selecting for talent, rather than total potential.

Some of this is probably wise. Nobody can learn everything, so it’s good to figure out which things you have more aptitude for. Resources for learning are also limited, so perhaps, for some esoteric skills, we should reserve those training slots only for the most talented.

But some of this is probably wasteful. I’m a big believer in mastery learning, whose central philosophy is that students who don’t immediately succeed with a skill ought to be spotted early and given extra explanations and practice to catch up. Too often, we punish early learning stumbles rather than help those students succeed.

2. We fail to sufficiently explain and break down complex skills and subjects.

Another reason some subjects seem hard to learn is that they’re not fully taught. The knowledge students need to fully understand the problem is skipped over to keep up the pace in teaching the class. The result is that some students can cross the gap and others cannot, making some subjects practically unlearnable for many students, even if they could learn it, in principle.

If you’re struggling with a subject, the safest assumption to make is that you’re missing the knowledge and component skills needed to make it easy. Those skills may take time to build—sometimes too much to keep up with a challenging class and still pass—but they’re buildable if you put in the time.

Learning anything can be made easier if we take the time to break it down and build up from the parts.

3. Our motivational hardwiring encourages us to find our niche.

We’re often motivated to pursue relative strengths rather than absolute ability. One study suggests that part of the gap in STEM participation between men and women is not, as is commonly suggested, due to men being better than women at math. Instead, a possible culprit is women being better than men at English—people choose to major in their best fields, which may unwittingly push women away from more lucrative career opportunities in STEM fields.

Sometimes this is adaptive. We focus on our strengths and avoid our weaknesses. But it can also be misleading because we may label ourselves “unartistic” or “numerically challenged” when our abilities are sufficient; they just aren’t quite as good as some of our other skills.

In this way, our belief that we’re only good at certain things may be reinforced when the reality is that we have the potential to learn almost anything—just at different rates.

How to Make Learning Easy (or at Least Easier)

All of this suggests a path for making learning easier. When you’re struggling with a subject, focus on background knowledge. Filling in any gaps in that background knowledge will expand your ability to juggle new information, give you stronger “hooks” to latch new knowledge onto and effectively make you smarter in the field of your choice. It may take more time, but it doesn’t have to be frustratingly difficult.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.