Learning requires focus. The reason is simple:

- Learning is a process of building long-term memories.

- You form long-term memories of what you pay attention to.

- Attention is limited. You can’t pay attention to multiple things at once.

But just because learning demands our focus doesn’t mean it can’t be enjoyable. Many activities put strenuous demands on our attention but we enjoy doing them anyway: video games, sports, puzzles and more.

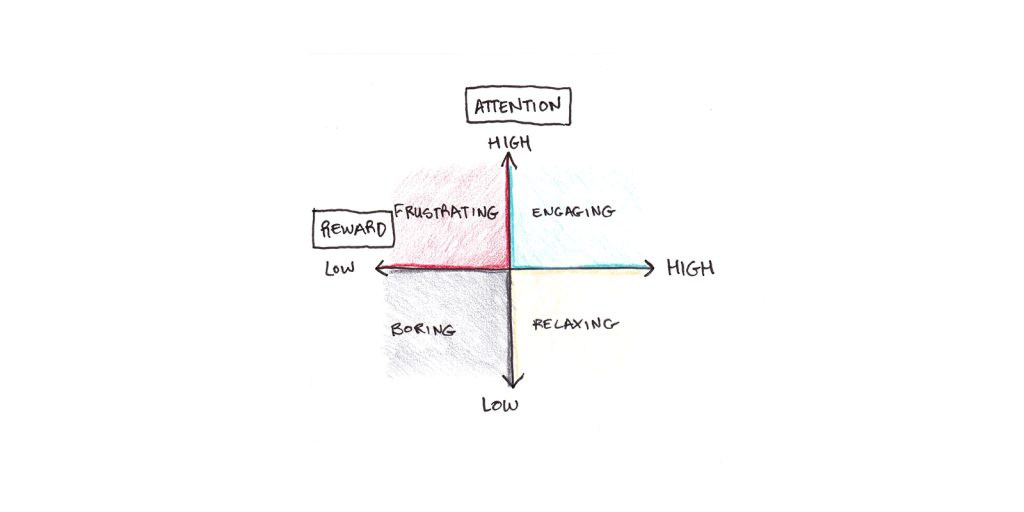

The opportunity cost theory of effort helps to explain the discrepancy. According to this theory, because our attention is limited, the motivational circuitry in our brain is constantly evaluating if what we’re paying attention to is a good use of this limited resource. Think of it like a busy manager trying to decide which jobs to put her limited staff on.

It feels effortful to do an activity that demands a lot of attention but doesn’t offer much reward. We may feel bored or amused by an activity that demands little attention, but it won’t feel hard. In contrast, it feels engaging to do an activity that demands a lot of attention and is highly rewarding.

According to the principles outlined above, effective learning can’t happen in the low-attention conditions. Subliminal learning is not a real thing. But we can make learning more fun by increasing the reward dimension. If learning is more consistently rewarding, it will be more engaging rather than dull or frustrating.

Five Ways to Make Learning More Fun

1. Keep your success rate high—aim for 85% correct.

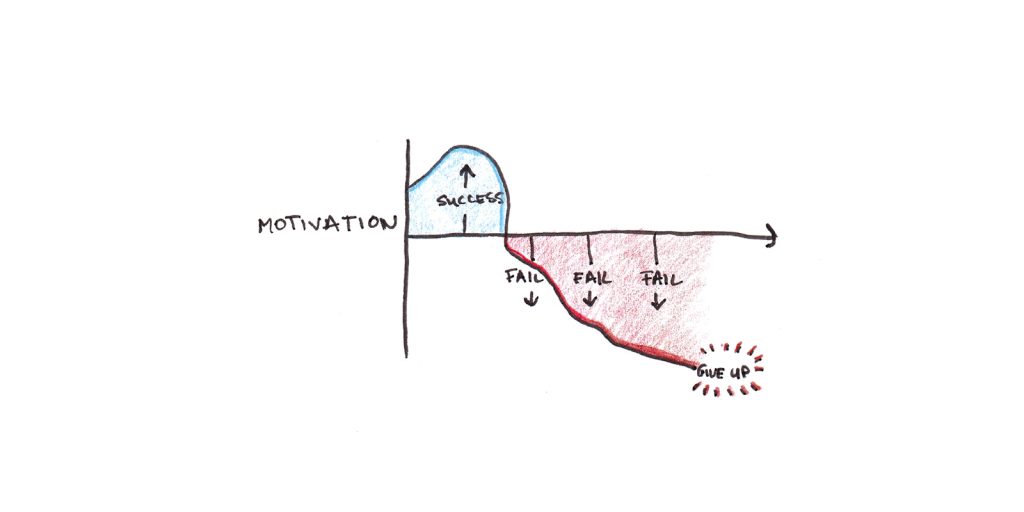

The experience of learning is a flow of tiny joys and frustrations. Consider going through flashcards: As you go through them, you probably experience mild bumps of interest whenever you get a card right, and mild dips of frustration whenever you get one wrong.

How much fun you have doing flashcards depends a great deal on the overall path of that flow. If you get too many cards wrong in a row, you will find the task more straining as the motivational centers in your brain look for other distractions. Conversely, if you easily get them all correct, the task may not require much attention—causing you to feel bored and distracted. Your attention has spare capacity that might be deployed elsewhere.

The key to enjoyable studying, then, is to set yourself up so that you’re getting most of the answers correct, but not so many that you start disengaging.

How can you control the difficulty of the activity? One way is to put the tasks on a sliding scale of difficulty. There are a few ways you can do that:

- Open book to closed book. The easiest form of practice is to work a problem with a nearly-identical example in front of you. The hardest is to solve a novel problem without access to any reference material. When studying, adjust your reference material to get to the sweet spot of mostly success with occasional failure.

- Work from simple to complex problems. A complex problem has multiple components that must be done correctly to get the answer right. So, one way to increase your success rate is to split complex problems into simpler parts. Alternatively, if the simple parts are too easy, you can tackle more complex problems that command your full attention.

- Change the standard you set for yourself. For problems with degrees of success, rather than simple right or wrong answers, you can adjust the difficulty by changing the standard you set.

- Adjusting the timing. Performing under time pressure can increase the difficulty. Similarly, relaxing time pressure can make a task easier.

Our ability to completely change the motivational flow of rewards within our studying is often limited. Thus, it’s unlikely that we’ll be able to take full advantage of video game designers’ tools to make studying as compelling as learning to play a new game. But, we can dial down the frustration in subtle ways to shift a draining task into an interesting one.

2. Reward yourself frequently.

Extrinsic rewards have a complicated history in psychology. Research has shown that explicit rewards can sometimes crowd out intrinsic motivation—if you pay someone to do a task, they may enjoy it less or stop doing it altogether when they stop being paid to do it, even if it is a task they might gladly do without being paid.

But, it would be a mistake to infer from this that we ought never to use extrinsic rewards. Some tasks will never invite much intrinsic interest, and rewards can be a powerful lever to make these tasks engaging, if not interesting.

A simple reward mechanism might be giving yourself a candy every time you finish a problem from your homework set. Another might be giving yourself “points” that you put on a tally whenever you succeed with a flashcard or read a section of your textbook.

Because extrinsic rewards can crowd out intrinsic motivation, avoid using them when the aim is to build motivation to perform an activity without rewards. But, if the studying activity itself is merely a necessary stepping stone to something genuinely more rewarding, liberally applying rewards can make the activity more enjoyable.

3. Eliminate temptations and distractions.

The opportunity cost theory of effort has an important implication: how much effort we perceive a a task requires depends on the implicit alternatives we have available to us. The strain of studying isn’t merely a property of that task; it’s also influenced by every other possible thing we could do in that moment with our limited attention.

Unfortunately, our attention environment has become saturated with low-demand, variable reward mechanisms. Social media provides a low-effort ping of enjoyment when we occasionally find something funny or amusing. Our phones offer a constant possibility for distraction.

Clearing our our attention environments is a good first step to making studying more enjoyable. Staying on task is easier when you don’t have your phone, computer, friends or television nearby. If you make studying this way a habit, focusing becomes easier since the distractions themselves are not available.

4. Smooth unnecessary friction.

Looking through the motivational lens again, we can see that the environment creates many micro-rewards and punishments that are not directly related to the task.

Consider getting set up to study. Maybe you need to find your book. And your desk is messy, so you need to clean it. And the chair isn’t comfortable, so you need to find a new one. And the fan is making an annoying sound in the other room … and so on.

Frictions are the little snags that make a task more effortful to perform. Reducing these barriers to get in the flow can make studying more fun. Since they’re external to the attention demands of learning itself, they’re also something you can improve without sacrificing effectiveness.

5. Make studying more meaningful.

Thus far, every suggestion I’ve made involves a task’s superficial rewards and punishments: Success rate, extrinsic rewards, external temptations and frictions. Getting these under control is essential since they’re the easiest to adjust directly.

But what we really enjoy in an activity isn’t just the shallow blips of pleasure and pain we feel while doing it. Instead, it’s the meaning that we give the activity and the meanings we experience while performing it.

Much of studying and learning is boring because it doesn’t feel meaningful. We can’t see the point of what we’re trying to learn. There’s no tangible connection to anything we want to do, achieve, understand or perform in our lives. As a result, there’s only a chore, drained of color, that has to be done.

Increasing meaning isn’t always easy for a few reasons:

- The importance of a piece of knowledge or method depends on its relation to other knowledge. Thus, we tend to find subjects more interesting as we learn more about them, as new information is built in a richer context. But this creates a Catch-22 in that we need to expend effort learning about something before we can appreciate learning it.

- Cognitive load may make meaningless drills necessary. Sometimes, the projects we find meaningful are too difficult to succeed at. We want to make the next Google, but the only program we can write is “Hello World.” We want to paint like Da Vinci, but can’t get beyond stick figures. Building up from fundamentals is often necessary, even if it isn’t always fun—thus, superficial tricks for boosting motivation may be an important tool for this phase of learning.

- The meaningful context is far away. We’re learning French, but our trip to France isn’t for months. We’re learning statistics, but our career as a data scientist is years off. In these cases, there’s a genuine motivation to learn, but distance from the desired outcome makes it impotent to drive the interest in the task itself. Researchers find that temporal delay is a central factor in procrastination.

But even if we can’t always make studying deeply meaningful, we can make efforts to increase the meaning we get from it:

- Read more on the background of the skills and knowledge you’re trying to learn. Getting more context can make what you’re learning make more sense—and be more engaging.

- Alternate between meaningful activities and the drills that support them. Doing real programming projects, having real conversations in another language, or doing real chemistry experiments—even badly—can provide a motivational backdrop for the necessary building blocks of learning.

- Find friends and forums for people interested in the skill. Social bonds can make an otherwise abstract task into something fascinating. Community can make learning compelling.

_ _ _

What strategies do you use for making learning fun? Share your thoughts in the comments!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.