Next week, Cal Newport and I are holding a new session of our popular course, Life of Focus. The course is a three-month program designed to help you become more focused in your work, life and mind—so you can pay attention to what matters most. This week, we’ll be sharing lessons drawn from the course. You can read the first lesson here.

The iPhone is less than two decades old. Yet the psychology behind why it is so hard to put your phone down has been understood for almost a century.

In 1898, the great psychologist Edward Thorndike proposed one of the first rules of behavior: The Law of Effect. Stated simply, rewarded actions tend to increase.

Just as a rat that gets rewarded with food when it pushes a lever tends to push the lever more often, every time we check our phones and get a viscerally rewarding stimulus, it strengthens our habit of phone-checking.

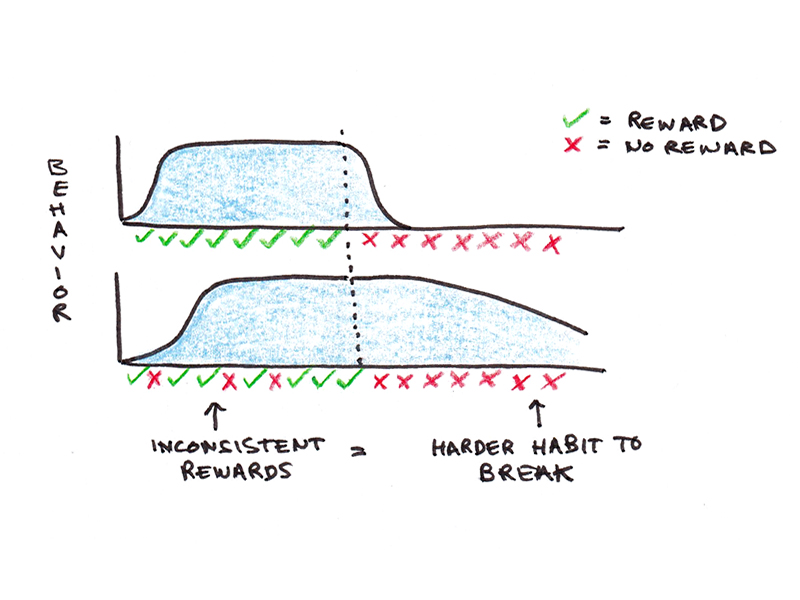

Given this relationship, a reasonable assumption would be that the more consistently an action is rewarded, the more durable the behavior will be. We might expect that a rat that gets a pellet every time it pushes a lever would push the lever consistently. Likewise, we might assume that a burst of entertainment every time we open our phones ought to make us thoroughly obsessed with them.

Except, this isn’t what early behaviorist psychologists discovered. Instead, unpredictable rewards tend to result in far more durable behavior. The rat that only sometimes gets a food pellet will persist in pushing the lever long after the machine stops dispensing pellets. The human being who only sometimes sees an interesting bit of news will keep refreshing her feed long after there ceases to be anything new or interesting.

Explaining Compulsive Phone-Checking

Why should unpredictable rewards be more robust than consistent ones? One explanation is adaptive: if I pull the lever and it reliably gives a treat, not getting a treat might indicate the resource has run out. In contrast, if treats only arrive some of the time, a steady period without rewards might just be a streak of bad luck.

This psychological quirk helps explain why slot machines are so addictive—and why social media algorithms compel us to check our phones, even though most of their content isn’t particularly interesting. The last twenty times may have been a dud, but maybe this next time …

Unfortunately, this law of behavior makes kicking our wasteful social media habits much harder. Just as a compulsive gambler keeps pulling the arm on a slot machine long after it has become clear the game is a losing bet, we continue checking our phones even when the value we get is far less than the price of constant distraction.

Kicking Digital Compulsions

In the second month of Cal Newport and my course, Life of Focus, we guide students through a digital declutter. For one month, you restrict non-mandatory social media and device usage. While one month isn’t enough to eliminate all the behavioral reinforcement built over years of phone-checking, it is long enough to provide some psychological distance that can help you evaluate which tools and services really are worth keeping—and which ones you don’t miss at all.

Next, we cultivate a more deliberate and conscious form of consumption. We help our students selectively bring back the tools, devices, websites and services they find useful—with carefully constructed guard rails so they won’t take over their lives.

If you’ve ever wished you could read more books, be more present with your family, or avoid the daily onslaught of negativity so many services seem to push, curated consumption is a saner way to deal with your online media.

_ _ _

If you found this lesson helpful, you should join Cal Newport and my course, Life of Focus, for our next session, starting on Monday!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.