Studying for school can be hard, but the process is pretty straightforward:

- Read all the material and attend all the lectures.

- Practice in ways that mirror what will be on the final exam.

- Use feedback to figure out what you need to fix.

Outside of school, though, this strategy breaks down. It’s impossible even to be aware of all the books that might be useful for any given subject, never mind actually reading them all.

In an infinite library, choosing what material to learn dwarfs even the largest difference in studying efficiency.

How to Choose What to Learn Next

Learning in an infinite library is a classic explore-exploit problem. You can choose to browse the library, read a few books, or study one intensively. Time spent on any option means less remains for the others.

Unfortunately, explore-exploit problems are intractable. There’s no method that will guarantee you’re spending your limited learning time wisely.

While there’s no surefire method to optimize the decision about what to learn next, I’ve found a few helpful heuristics.

Heuristic #1: Start with Textbooks

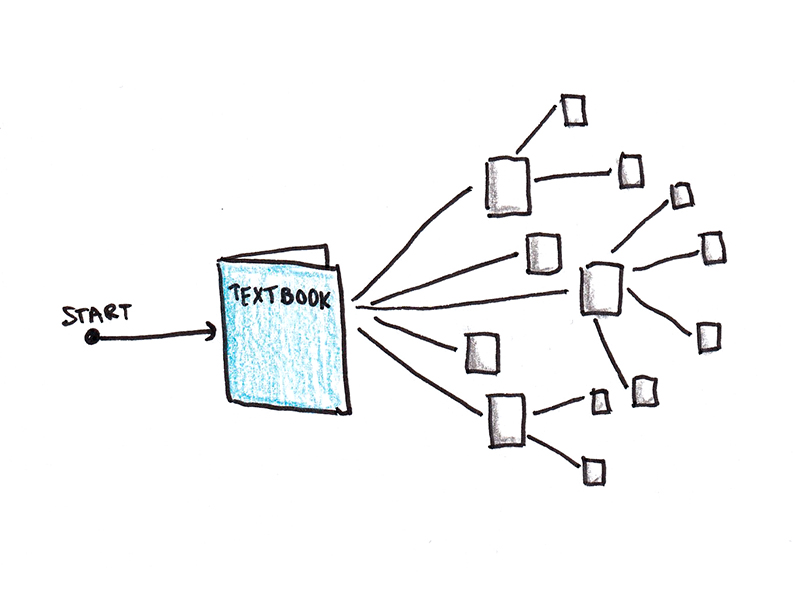

The best book to read first on a new topic is usually a textbook. They’re written for students, so jargon is defined, and necessary concepts are explained. They also tend to be balanced in their coverage of the field. Even authors who write polemical treatises tend to give a fair report of the domain when writing a textbook.

Textbooks also serve three additional functions:

- They introduce you to a field’s basic language and concepts, providing the foundation to understand more specialized books and texts.

- They cite key papers and research, giving you a further reading list.

- They introduce terms and technical language, which you can use to search for more reading material.

Literature review papers can also be useful as a first introduction to a topic. Literature reviews usually cover topics that have a relatively large body of accumulated research but are too narrow or new to fill a textbook. These can be harder to read than textbooks because they’re often written for academics and presume the reader is familiar with the discipline, if not the subtopic being reviewed.

Heuristic #2: Use Specific Projects to Overcome the Effort Hurdle

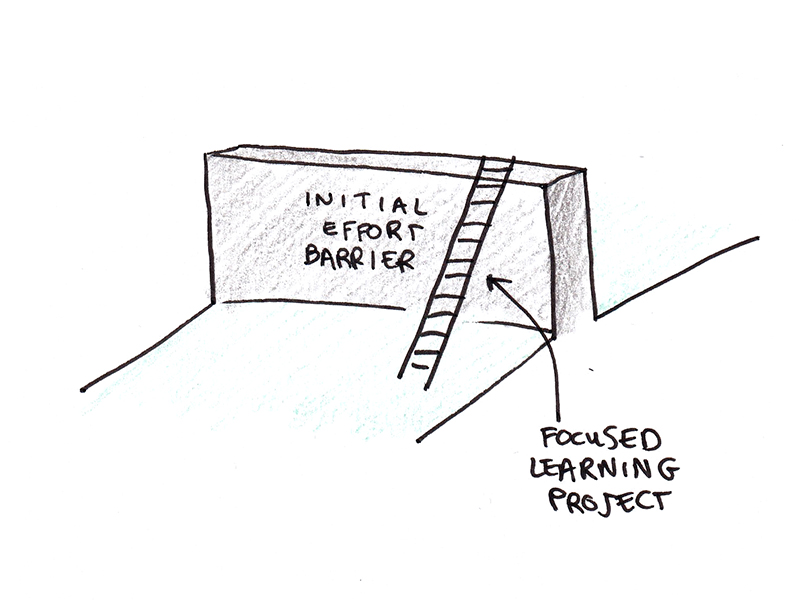

Often, reading about a topic is enough to learn what you need. Given that the alternative is often doomscrolling social media or binge-watching Netflix, simply spending enough total time learning is a vital first step.

But reading alone isn’t enough to master a topic. An almost gravitational pull urges us to avoid the more effortful parts of learning. It’s easier to watch lectures than to do practice problems. It’s easier to read a fun explainer than to dig into the primary sources. Without any forcing mechanism, self-directed learning tends to stick to the surface.

The best way I’ve found to overcome this problem is to establish specific learning projects with clearly defined goals. This is especially successful when a topic has some drudgery that must be pushed through before the skill or topic becomes naturally engaging.

Heuristic #3: Follow Smart People, Save Their Recommendations

While collecting books on your bookshelf is easier than actually reading them, the two are not in opposition. I would argue that a major reason people don’t read is that they don’t have, at hand, any books they find particularly interesting or compelling to read.

This problem is trivial to solve in today’s world. Follow people who have some overlap with your interests who regularly write book reviews or post their reading lists. Whenever a book recommendation piques your interest, download a Kindle sample to your phone.

Then, whenever you don’t have a book you’re excited to pick up and read, scroll through and read some of your samples until one grabs your attention. While you will likely end up deleting many of the samples without reading the whole book, having them available ensures you always have a steady supply of interesting books.

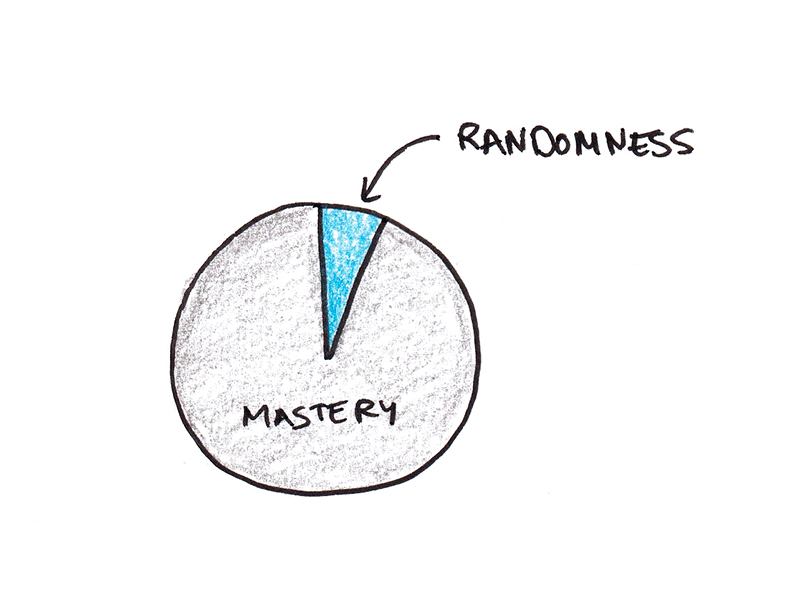

Heuristic #4: Allocate 10% of Your Study Time to Weird, Unfamiliar Topics

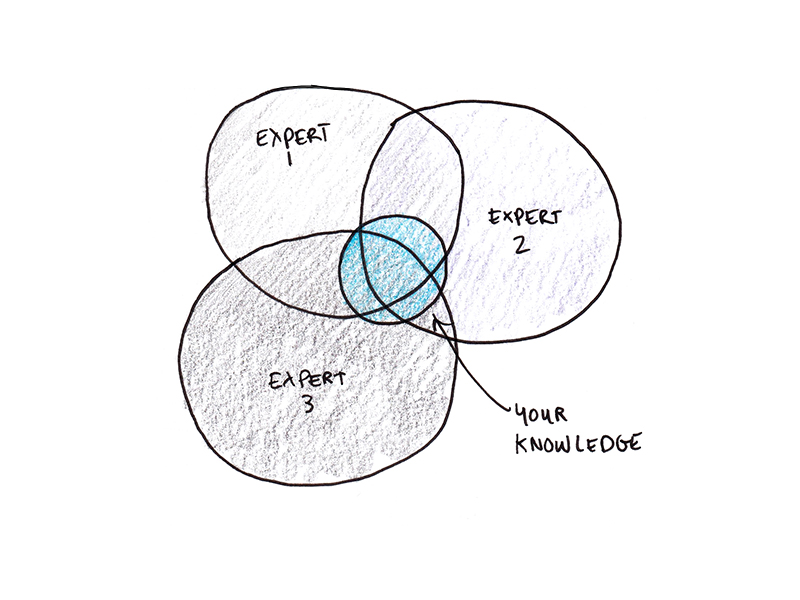

There’s nothing wrong with cultivating particular interests and areas of expertise. But I think two factors make specialization self-reinforcing, even if we’d prefer more breadth:

- Familiarity with a subject makes it easier to read new books on that subject, thus lowering the effort cost.

- Books refer to other books and resources in that same area, populating our future reading lists with more on the topic we are already studying.

One potential counter to this is to deliberately reading and studying books on topics you know nothing about. Some of my favorite books I’ve found through this process include books about fungus, jazz, and epistemology in ancient China.

And your studies shouldn’t just be confined to books! Bookishness is itself a kind of comfort-induced specialization that can be broadened by learning to cook or garden or immersing yourself in another culture.

What strategies do you use to decide what to read or learn next? Share your thoughts in the comments!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.