Human reason is a puzzling ability. As a species, we’ve invented logic, mathematics, science and philosophy. Yet we suffer from a list of cognitive biases so long that an entire Wikipedia page is devoted to categorizing them.

So which is it: are we excellent at reasoning or incurably irrational?

Psychologist Philip Johnson-Laird has spent his career working out the answer. His theory of mental models explains how we have the ability to reason correctly—and also why we frequently fail to do so.

I recently read Johnson-Laird’s nearly 600-page book, How We Reason. The book weighs in on an impressive variety of topics related to reasoning:

- Why do some people reason better than others? (Mental models require working memory, which is both limited and varies between individuals.)

- Why are some puzzles harder than others? (The more mental models a correct inference requires, the harder it is to deduce the correct answer.)

- Does reasoning differ between cultures? (Johnson-Laird argues the basic mechanisms are universal, but there can be differences in knowledge or strategies.)

- Do people with psychopathologies reason more poorly? (It may actually be the opposite! People with obsessive-compulsive disorder actually reason better when the content of the reasoning questions was related to their obsessions.)

- How does visualization impact reasoning? (Images often occur alongside reasoning, but imagery itself can actually make reasoning worse!)

- Can we improve our ability to reason? (Johnson-Laird is cautiously optimistic, suggesting a method based on mental models his research found dramatically improved performance.)

To understand these questions, and Johnson-Laird’s proposed answers, let’s walk through what the theory of mental models argues, how it differs from some prominent alternatives, and what that implies about how we think.

What are Mental Models?

To understand the theory of mental models, let’s look at a basic syllogism:

- All men are mortal.

- Socrates is a man.

- Therefore …

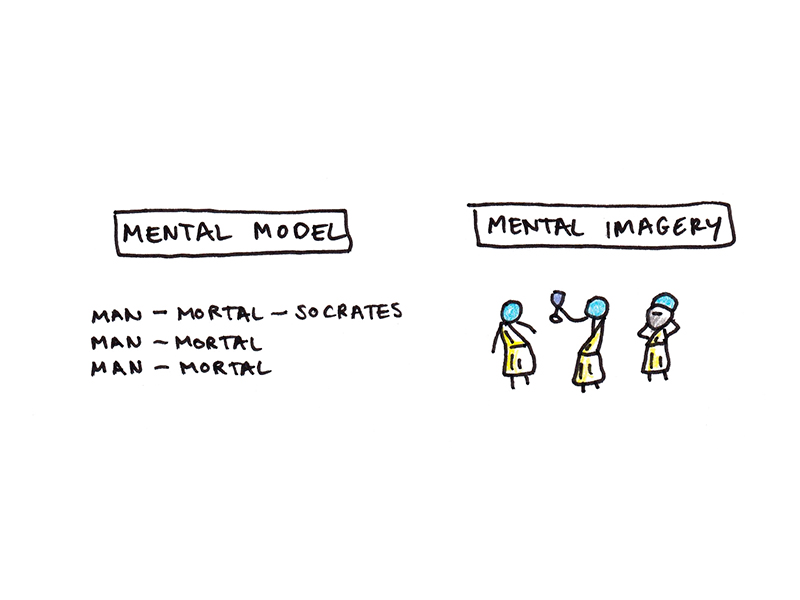

According to Johnson-Laird, we reason by simulating possibilities described by the premises: As we read the first premise, we generate a mental representation of a few men and assign each of them the property “mortal.” As we read the second premise, we pick out one of these anonymous men and indicate that it is Socrates.

man – mortal – Socrates

man – mortal

man – mortal

…

Inspecting this model, we can immediately conclude that Socrates is mortal.

Mental models are not the same thing as mental imagery. It isn’t necessary to visualize little Athenians in togas, one of whom is Socrates, to make the correct inference.

Indeed, a property like “mortal” doesn’t have an immediate visual representation, so it’s not obvious how it could be inferred from an image.

Mental models are abstract, but they are structured in a way that reflects the situation they represent.

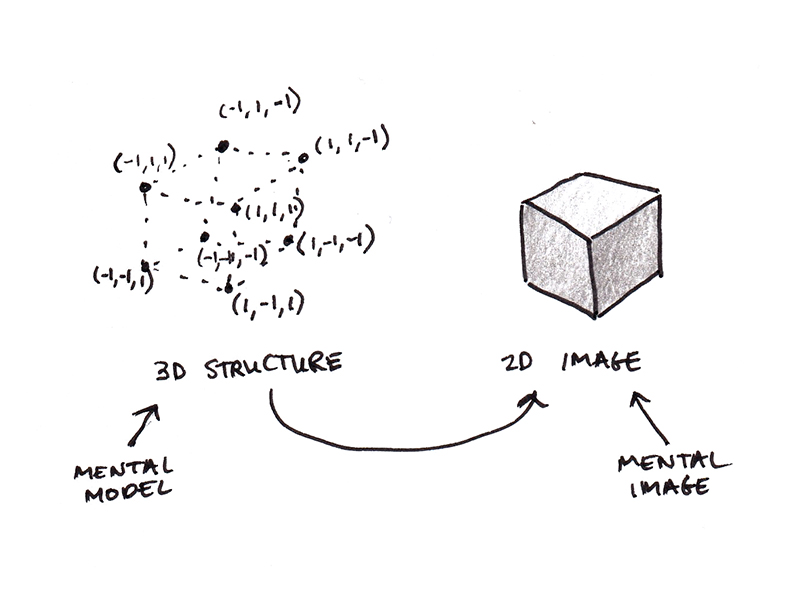

For instance, Johnson-Laird explains that when we mentally rotate an object, the mental model we’re rotating is a three-dimensional representation of the object. However, the mental image we see in our mind’s eye is the image of that 3D object when viewed from a particular vantage point.

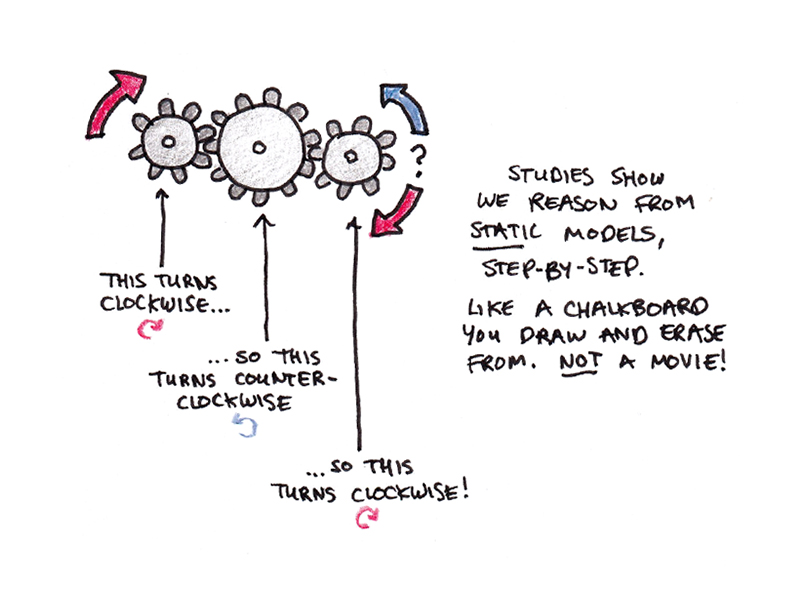

While imagination often feels like a movie we can play and rewind, mental models are static. When we reason about a dynamic situation, such as figuring out the effect of turning a particular gear in a complex machine, we typically simulate each component’s effect sequentially. Our reasoning is like a static diagram we draw and erase from as we work through each step.

In brief, a mental model is not an image or a movie. Rather, it’s an abstract representation that contains one possibility based on the information given. We reason by manipulating these representations: adding properties, moving them around and inferring conclusions by directly inspecting them. The contents of the mental model are conscious, but the mechanisms used to generate and represent them are not. Thus, while we can use mental models to reason, we can’t directly report how they’re organized in our minds like we can for mental imagery.

Why is Reasoning Possible? Why Does it Often Fail?

I started this book review by noting the puzzle of human reason: We’re a species that has invented calculus—yet frequently fails at basic arithmetic.

Consider the following question:

A bat and a ball cost one dollar and ten cents. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

Many people instinctively respond with “ten cents,” but that can’t be right. If the ball cost ten cents, the bat would need to cost one dollar and ten cents, bringing the total to $1.20. The correct answer is five cents, but many otherwise intelligent respondents get it wrong.

Dual-process theories suggest that we use two different psychological systems to answer these questions. System 1 is fast, automatic and effortless. Because ten cents and one dollar and ten cents are both in the problem statement, and one dollar is their difference, the question immediately provokes a tempting System 1 answer to the question: ten cents.

System 2, in contrast, is slow, effortful and calculating. Mental models are a theory of how reasoning happens in this system. Rather than the rapid, intuitive response given by the first system, to use mental models, we need to mentally construct the situation described and inspect it to determine the right answer. Many failures of our reasoning are simply accepting a tempting System 1 answer instead of doing the hard work of reasoning the question out using System 2.

Reasoning failures don’t occur just because we rely on misleading intuitions. They can also happen when the problem requires us to generate more mental models than we can fit inside our limited working memory.

Some reasoning problems are relatively straightforward. Consider the following:

Some of the authors are bakers.

All of the bakers are bowlers.

What, if anything, follows?

The easy deduction, “Some of the authors are bowlers,” occurs quickly because the conclusion is evident after only constructing a single mental model:

author – baker – bowler

author – baker – bowler

author

author

…

But other problems are more difficult. Consider:

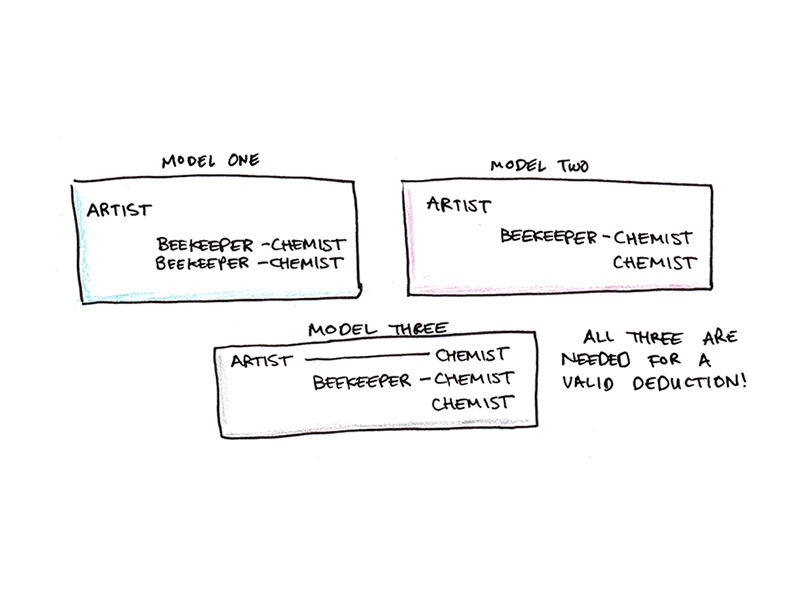

None of the artists is a beekeeper.

All of the beekeepers are chemists.

What, if anything, follows?

Some people offer invalid conclusions such as “None of the chemists is an artist,” or state that nothing interesting follows from those premises. Very few, according to Johnson-Laird, draw the correct conclusion, “Some of the chemists are not artists.”

Why is this problem so much harder than the first?

We need to construct not just one, but three different mental models to represent all the distinct possibilities implied by the premises. Then, we must compare those mental models to find a deduction that holds true for all of them.

Johnson-Laird argues that three mental models are at the outer range of our working memory capacity, so most people will fail at this reasoning. However, we can augment our working memory by offloading some of the models to pencil and paper.

In an intriguing experiment, subjects were given a pencil and paper and instructed: “Try to construct all the possibilities consistent with the given information.” This approach encourages people to generate more models and makes it more likely that they can draw a correct inference.

Johnson-Laird compares the performance with reasoning puzzles:

Without the benefit of the model method, the participants were right on about two-thirds of the trials, and they took an average of twenty-four seconds to evaluate each inference. With the benefit of the method, however, they were right on ninety-five percent of the inferences, and they took an average of fifteen seconds to evaluate each inference.

Mental models are cognitively demanding. Thus, we often fail to construct a mental model and go with a cheap and fast System 1 response. Or, we get so bogged down in trying to construct alternative possibilities that we fail to make a valid conclusion. Yet our difficulties in reasoning are not insurmountable. Johnson-Laird explains:

If humans err so much, how can they be rational enough to invent logic and mathematics, and science and technology? At the heart of human rationality are some simple principles that we all recognize: a conclusion must be the case if it holds in all the possibilities compatible with the premises. It doesn’t follow from the premises if there is a counterexample to it, that is, a possibility that is consistent with the premises, but not with the conclusion. The foundation of rationality is our knowledge that a single counterexample overturns a conclusion about what must be the case. [emphasis added]

Comparing Mental Models with Alternative Theories

Mental models are a neat theory, but is the theory true? Proponents of a given theory can nearly always point to compelling evidence in its favor. Sometimes, even spurious theories can sound plausible, especially if you haven’t devoted a career to noticing their flaws.

So, what’s the status of mental models?

My understanding is that Johnson-Laird’s theory is one of the leading psychological theories of reasoning, even though it doesn’t have the status of being a consensus theory (few theories in psychology do). The principle alternatives (which Johnson-Laird spends quite a few pages debating against) are:

- Formal theories. In these theories, we reason the same way that logicians do, paying attention to the logical structure of sentences rather than their meaning.

- Bayesian networks. Bayes’ rule is a way of updating the amount of confidence in a belief when we encounter new evidence. Some theorists argue that our brains implement a version of this rule, allowing us to make inferences with incomplete or uncertain information.

- Content-specific rules. Instead of a single broad reasoning faculty, perhaps we reason with different mechanisms for different types of situations. One prominent theory, for instance, explains reasoning failures as an ability to detect rule violations rather than a general ability to reason about conditionals.1

Practical Takeaways of Mental Models

Inferring practical tips from a purely descriptive theory is often speculative. Research into general problem-solving heuristics encouraged many researchers to consider instruction in problem-solving skills as critical, but we now realize that was probably a mistake.

Similarly, while it’s easy to squint at Johnson-Laird’s results and come up with takeaways, some of those are probably illusory. His finding that imagery may interfere with mental models shouldn’t imply that suppressing mental imagery is necessarily helpful. (Indeed, a lot of anecdotal evidence in math and physics suggests the opposite!)

With that caution in mind, a few tentative takeaways of mental models might include:

- Use pencil and paper to construct complete models for complex situations. Programmers, for instance, often introduce bugs when they fail to mentally simulate all the possible settings for variables and an unanticipated combination of settings results in an error. Working through all the possibilities with pencil and paper can help to overcome insufficient mental models.

- Knowledge supports reasoning. According to mental model theory, knowledge modulates our interpretation of logical premises. A complete logical model of “Jim’s either in Rio or he’s in Brazil” includes the possibility that he’s in Rio but not Brazil. However, most participants never consider this possibility because they know that Rio is in Brazil. Knowledge trims extraneous possibilities and allows for reasoning to proceed with less cost to working memory.

- Use base rates to avoid thinking mental models have the same probability of being correct. Johnson-Laird argues that we reason about probabilistic events by constructing possibilities and weighting them equally by default. But this biases our reasoning toward rare and unusual events. Plane crashes are easy to visualize, but occur very rarely, so we overweigh their likelihood compared to the thousands of interchangeable mental models when the plane lands without incident. Base rates, the practice of assigning probabilities based on the statistical likelihood of similar events, can improve the accuracy of risk calculations.

- Discuss and share your mental models. A weak point of human reasoning is that we struggle more with generating counterexamples than we do with recognizing them. The famous Wason four-card task tricks most participants, but accuracy improves greatly when people are allowed to discuss and explain their choices, as there is an increased chance of successfully recognizing a counterexample.

If you’re interested in learning more about mental models and Johnson-Laird’s theory, I can recommend both his original 1983 book, Mental Models, as well as his 2006 summary of the state of the theory, How We Reason.

Footnotes

- I previously reviewed Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber’s The Enigma of Reason, which suggests a modular theory of reason. However, as anthropologists, their theory tries to provide an evolutionary account of reasoning, rather than explaining the computational mechanisms of underlying reasoning.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.