I recently finished listening to Rich Roll’s memoir, Finding Ultra, on audiobook. Hearing about a guy who completed five Ironman triathlons in a single week is great motivation to not wuss out when you’re in the middle of a run.

But while Roll’s story is undoubtedly inspiring, it got me thinking about a central question in my pursuit of building better foundations: how much is good enough?

Fitness, like most foundations, has ample benefits. It makes you healthier, increases energy, boosts cognition and helps you live longer. Yet it seems our brains didn’t evolve to make us like to exercise, so as a society, we’re chronically out-of-shape.

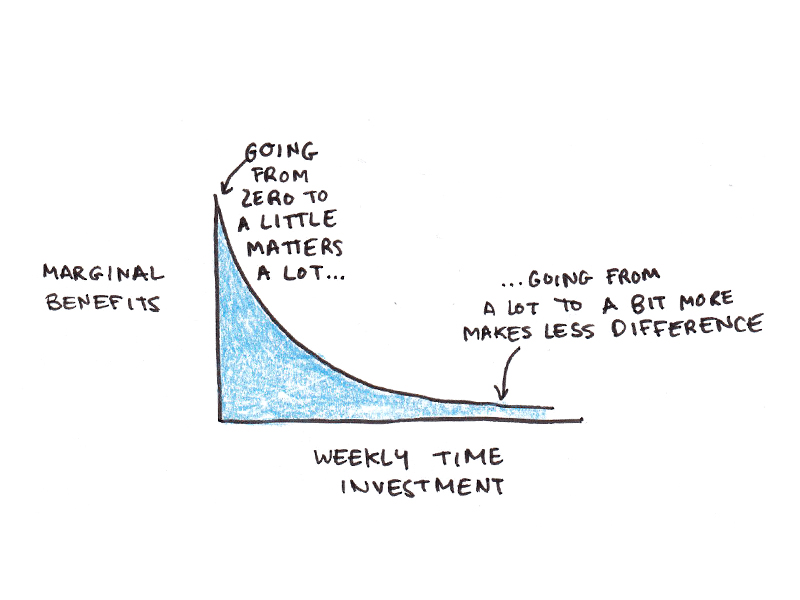

The benefits of exercise form a classic diminishing returns curve. People who do zero exercise benefit tremendously from moving a little. People who meet recommended minimums still benefit from exercising more, but it’s a smaller improvement than going from no exercise to some. The common advice amongst fitness advocates seems to be, “Some exercise is good; more is better.”

But there’s more to life than just staying in shape.

Even Roll, for all his incredible accomplishments, noted many of the drawbacks his intensive training initially generated: his focus on training led to the decline of his legal practice, putting his family through financial challenges, and his wife had to manage a larger share of the household work. Roll turned his success into a best-selling book and popular podcast. But for the rest of us, fitness is a side-hustle, not a career.

The question isn’t limited to exercise. Several years ago, I went on a ten-day meditation retreat. When the retreat finished, it was impressed upon us that the way to maintain our newfound mental clarity was to meditate for two hours every single day.

How do you get the balance right? How do you decide how much to invest in a foundation, and when do you decide you’re already doing enough?

Here’s The Wrong Way to Answer This Question

Let’s start with how we typically make decisions of this kind: we look around us, see what other people are doing, and make a decision based on what kind of investment seems “normal.”

Delegating decisions of this kind can be adaptive in many areas of life. The cultural evolution hypothesis argues that cultures can adopt beneficial practices without necessarily having a good rationale for their existence.

Indigenous farmers learned to mix small amounts of ash into corn when cooking it, which prevents niacin deficiency. Europeans who brought corn back as a food crop often suffered from pellagra owing to their lack of this technique. Yet neither group knew anything about vitamins. Cultural practices evolve, and thus, social norms can embody wisdom.

However, cultural evolution and the slow embedding of wisdom into practices take a long time, and our environment has transformed quickly. Continuing the example of fitness, few traditional cultures share our modern concept of exercise, despite the overwhelming evidence that most of us ought to do more of it. Until recently, daily life was enough to keep in relatively good shape.

Thus, looking around you and seeing what others are doing, while a good long-run strategy, will fail in exactly those circumstances where our environment has changed too rapidly for biological and cultural evolution to catch up. For each of the foundations I listed last week, there’s such a story that explains why we underinvest.

What’s a Better Way to Decide How Much is Enough?

The correct way to make these kinds of decisions about tradeoffs comes from economics. The formula is relatively simple, even if the quantities involved are harder to calculate:

- Add up all the benefits of investing an additional unit of time, effort, attention or money.

- Add up all the costs of spending those resources, including the opportunity cost of doing something else.

- Continue investing more in the foundation until additional costs equal additional benefits.

To consider this, let’s go back to our fitness example. What are the benefits of exercise? Health is the most obvious, but there’s also increased energy, cognition, mood and, of course, looking good.

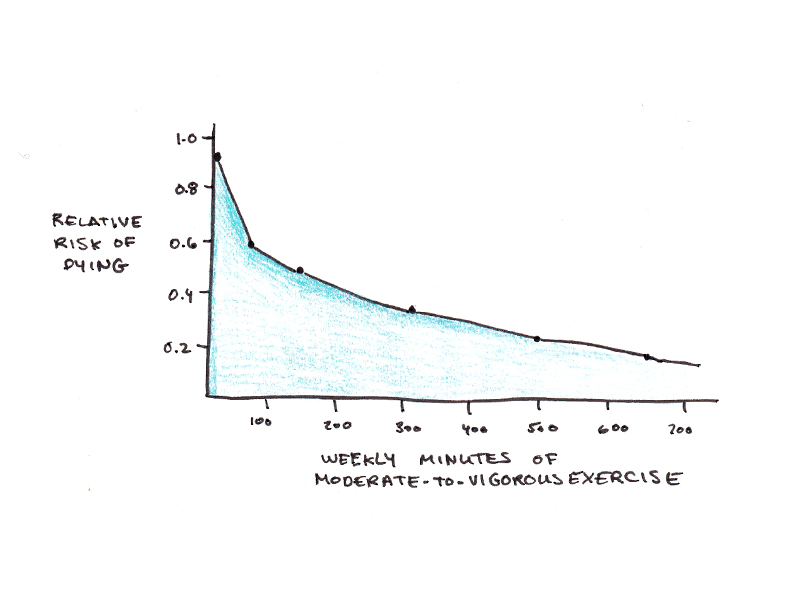

Physical health is perhaps the easiest to quantify since there are many studies looking at mortality rates, coming from epidemiological work looking at cohorts of individuals who vary in their fitness levels.1

To this curve, we need to add the other benefits of exercise. Simplifying it a bit, we get something that looks like this—each additional minute of exercise brings a lot of benefits at first, slowing down over time as the quantity increases:

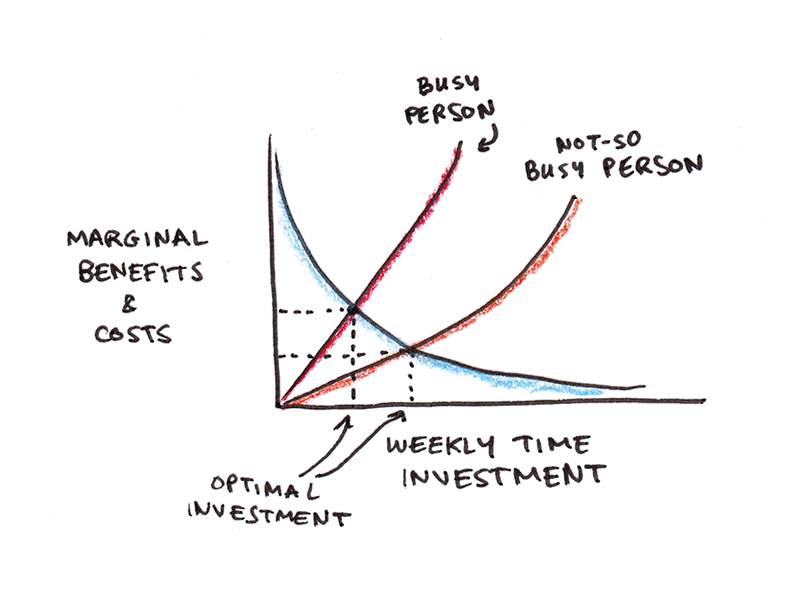

What about costs? Exercise enough and the willpower needed to exercise becomes quite modest. While you can get injured during exercise, regular exercise also prevents injuries by strengthening bones and joints, so as long as the workouts don’t ramp up too quickly, this is probably a net benefit rather than a cost. This leaves the main cost as the time required to work out.

Although the benefits of exercise are relatively universal, the cost equation does change for different people. If you work two jobs, have six kids and study on weekends, an additional half an hour for anything is incredibly costly. Conversely, if you’re single and only work part-time, you may find it easy to spend hours a week on television or video games without much impact on the rest of your life.

Costs tend to go up as you spend more. Doing one minute of exercise per day requires almost no sacrifice. But the price gets higher as you need to cut into more valuable alternative activities to find time. For a busier person, this rise is steeper, since there is comparatively less “slack” in her schedule:

Finding Balance

Actually calculating the optimal crossover point where additional benefits equal costs is difficult to do in practice. Many of the costs have no shared standard of measure, and it may be hard to get accurate figures for, say, the exact impact of an extra ten minutes of exercise on brain health.

But just because we can’t find an exact result doesn’t mean this analysis is useless.

Instead, I’d argue that we can do an informal version of this thinking whenever we make decisions about how much we should, ideally, invest in each foundation:

- What is the additional benefit of doing more in this foundation?

- What is the opportunity cost? What would I have to stop doing to make that investment?

- Is the trade worth it in the long-run?

Long-run costs and benefits are what’s most crucial to this calculation. Most foundations have substantial upfront investments, even if the ongoing costs are quite reasonable. This can be because it takes awhile to get a system up and running, such as when you start a new productivity system or start investing. But, typically, the initial costs are high because investing in that foundation isn’t a habit and thus requires a lot of attention and self-control to implement.

However, once you pay those fixed costs, you can reap the benefits of strong foundations for the much more modest “maintenance” costs. Most people who have a good productivity system, solid financial portfolio or healthy eating habits aren’t expending a lot of time and energy to sustain them.

One justification I can see for engaging in a serious effort to build foundations over time is that it enables you to push closer to the true optimal point. Once you get over the initial barriers of setup and habituation, you can reap the rewards with much less effort.

Footnotes

- A major concern with epidemiological studies is separating causation and correlation. Does exercise cause people to live longer (causation), or do other variables cause both exercise and good health (correlation)? Probably some of both, but multiple converging lines of evidence that don’t suffer from this problem suggest that the effect of exercise on health is causal.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.