I’m launching my new program, Foundations, in one month. It is a 12-month course designed to help you build or improve the essential building blocks we all need to live a good life. It’s also a learning project for myself, which I’ll be covering on the blog.

A common misconception I’ve seen since I first started writing about foundations is that having a solid foundation is, essentially, just a result of having good habits.

Habits are essential, but focusing exclusively on habits can be misleading to both the short-term requirements for self-improvement as well as challenges in maintaining change long-term.

What Habits Are (And What They Aren’t)

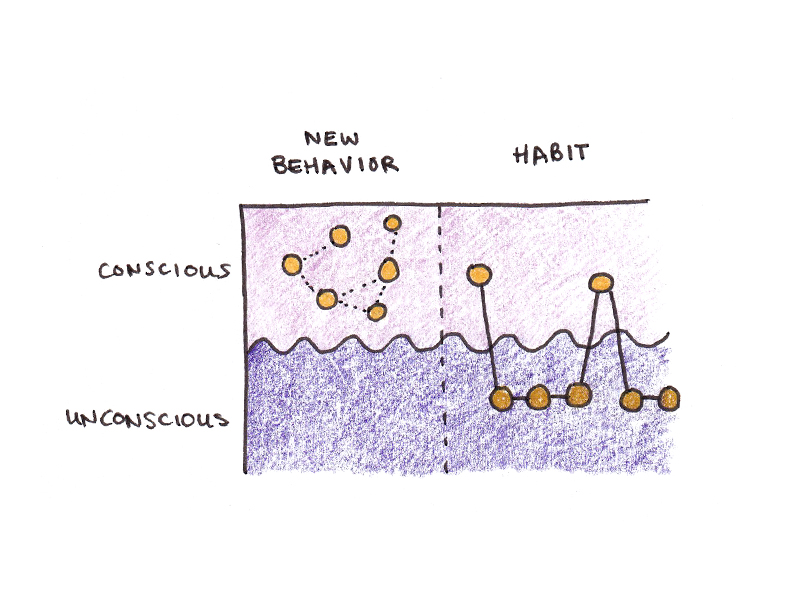

Simply put, a habit is any behavior that has been at least partly automated. Habits are behaviors we can perform without significant effort, attention or thought.

I use the words “partly” and “significant” here because most real-life behaviors cannot be completely automated. This was one of the central findings of Shiffrin and Schneider’s original experiments on controlled and automatic processing.1

As we repeatedly perform a behavior, such as trying to form a habit or practicing a new skill, some parts of the skill get offloaded to areas of the brain that do not require conscious attention to operate. However, other parts of decision making continue to require conscious control.

Consider driving a car. When you first learned to drive, you needed to pay attention to everything—from which pedal was the gas pedal to how much to rotate the steering wheel to turn the car’s tires the right amount. Eventually, most of these things became mindless—you just drive the car without minding the details. But, even in these cases, we still need to pay attention while we drive, or we’ll get in an accident.

Similarly, when we build a new habit, such as regular exercise, healthy eating, or reading more books, some components of that action get automated, making it easier to do the right thing. But it rarely reaches a point where the behavior is completely on autopilot.

Habits alone are probably not enough for most people to sustain long-term changes.

What Else Do We Need to Make Changes Last?

If effortless habits aren’t enough, what else do we need to make long-term changes stick?

I can think of several different psychological processes that make behavior change last in the long term, including:

- Knowledge. While knowing the right thing to do is not typically the bottleneck for most people, it supports motivation and decision-making. Someone who understands how investing works isn’t guaranteed to make wise choices with her savings, but she will be more likely to grow wealth than someone who thinks investing is just a form of gambling.

- Self-efficacy. While habits are unconscious biases toward certain actions, self-efficacy is a conscious belief in your ability to take those actions. I suspect many out-of-shape people stay that way because even the thought of exercising every day seems unmanageable. Forming habits helps, but a “fit” person—who trusts themselves to exercise regularly—can often switch to completely different exercise routines without difficulty because they believe exercising is fun and easy.

- Rules. We all cultivate rules for our own behavior, even if we can’t always consciously articulate those standards. A person might be completely self-indulgent with alcohol and junk food, for instance, but never consider taking hard drugs. A rule isn’t just a behavioral tendency but a standard you hold yourself to across disparate situations.

- Courage. As I share in my latest book, fears are largely provoked by unconscious threat-detection circuitry. These perceived threats bubble up into our consciousness as fears and anxieties, even though we often can’t rationalize their source. Exposure to the situations that trigger our fears without experiencing undue harm can make action easier.

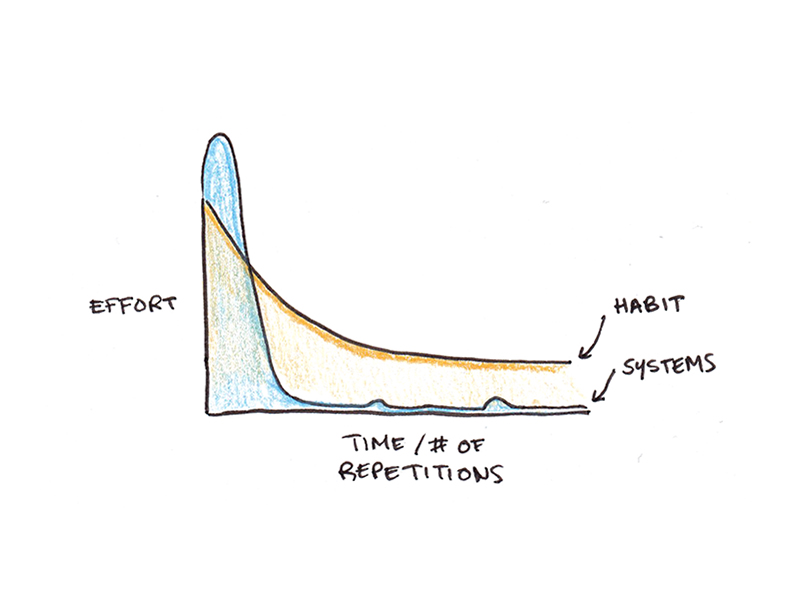

- Systems. Using an explicit tool, like GTD for your productivity, index investing for your finances, or a calendar-based system for managing your professional commitments can offload some of the mental work of trying to make the correct decision all the time. Just as it’s easier to use paper notes than to memorize text verbatim, sometimes the best way to instill good behaviors is to avoid relying on your brain to execute those behaviors in the first place.

- Identity. How we see ourselves reflects the behaviors we consider appropriate. Identity is often a lag measure of behavior: we tend to see ourselves as the kind of person who does what we typically do. While there are exceptions to this, how we identify ourselves can be a potent sustaining factor for change even when habits have long broken down. Consider an athlete who has to take a year off training to recover from an injury. If he continues to see himself as an athlete, getting back into fitness underscores that identity and is a naturally compelling goal, not a forced behavior.

In other words, we need a lot more than just automatic behaviors to sustain a change. We need knowledge to guide the right actions, self-efficacy to know we are capable of taking them, rules and systems for managing decisions, courage to overcome our fears and a shift of identity to sustain it throughout the innumerable disruptions that will occur in life.

Why Taking a Bigger Picture of Change Matters

This may all sound somewhat pedantic. After all, few people who advocate for habit change argue against doing the other things I suggest above. Nobody I know of believes that change occurs purely through automation.

However, it’s important to recognize some of these complexities because they shape our understanding of how change can be motivated and sustained.

To take just one example, consider the complex skill of public speaking. Unless you’re giving the same speech over and over, it’s unlikely that much of this skill is going to be automated. This is especially true if you speak in many different situations and contexts.

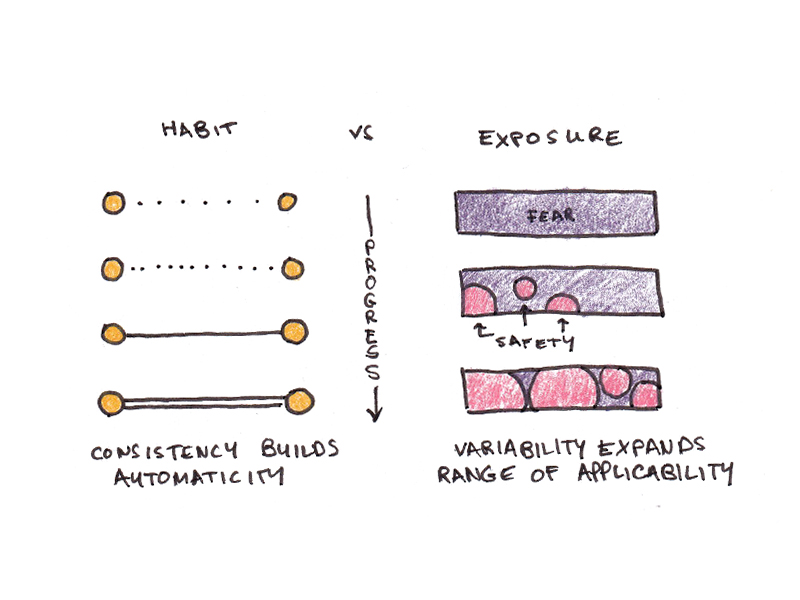

Practicing public speaking dramatically reduces the fear associated with standing on stage. Thus, repeated exposure will make it much easier to do.

The primary bottleneck to change in this example is courage, not habit, which gives us a clue as to what approach is needed. Exposure works best when you vary the context and cues to provide a robust signal of safety. This is somewhat the opposite of typical habit-setting advice, which argues for increasing consistency in order to accelerate automaticity.

Similarly, since we aren’t aiming for an automatic habit but simply a greater feeling of ease, it probably makes more sense to go overboard in the beginning—doing a lot more speaking than one plans to sustain long-term, so that the feeling of fear can drop dramatically, rather than try to ration it out the way one would if you were planning a really long-term habit.

Public speaking isn’t a foundation I’m considering for my own twelve-month effort, but outreach, where the month’s focus is on creating opportunities to meet new people and build weak ties, is analogous in many ways.

Another example could be productivity and personal finance, which are sustained by having good knowledge and systems. In both cases, a system that requires a lot of habits—rote actions you need to take regularly to keep the system running—is probably a sign of bad design rather than a virtue.

Sustaining Change

When discussing my Foundations project, a friend asked if I am giving up on the learning theme so prevalent in my blog. It’s the opposite. Having spent much of the last decade diving deep into the psychology that underlies motivation, learning and behavior change, I feel like that is my default lens for viewing any other topic.

It’s also a lens I hadn’t yet built when I embarked on my first foundation-building self-improvement decades ago. As a result, I often designed my efforts at improvement badly—either misunderstanding the nature of the change needed or failing to appreciate how all the above factors, not just habits, influence how we sustain long-term changes.

I’m excited, then, to apply this new lens to the upcoming project. Not only do I want to strengthen some of my own foundations, but it is also a meta-project exploring the practical art of making changes. Ultimately, the most crucial knowledge is self-knowledge—since its through it that all other learning is possible.

Footnotes

- Specifically, they found that certain types of simple tasks that required variable binding of elements required some conscious involvement. Other research, such as Daniel Kahneman’s work, has also found that while intuition and automatic processing are powerful, they have sharp limitations. The unconscious mind is almost certainly *not* analogous to the conscious mind but a completely different collection of cognitive tools and functions.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.