Focus is essential to productivity. But it’s tough to stay focused when you’re anxious.

This is a dilemma I’ve faced quite a bit in my own work. As I’ve written before, I’m a somewhat anxious person by nature—and that can wreak havoc when I’m worried about the things I need to work on.

Worries deal a double whammy for our success with difficult cognitive work:

- Anxiety encourages avoidance. If you’re afraid of doing badly on a test, bombing a presentation, or getting your submission rejected, one strategy to avoid those negative feelings is simply to avoid working on the project that is causing you to feel anxious. This avoidance itself, however, can perpetuate anxiety by preventing you from experiencing that those worries were most likely overblown.

- Anxiety uses up mental bandwidth. Worried, intrusive thoughts are distracting. More technically, they use up your working memory capacity, leaving you less capacity for your tasks. This can be disastrous for deep work or intensive learning as we need every bit of working memory capacity we can muster.

Below are a few strategies, culled from psychotherapeutic approaches for dealing with stress, that have helped me:

1. Apply Socratic questioning to your reflexive thoughts

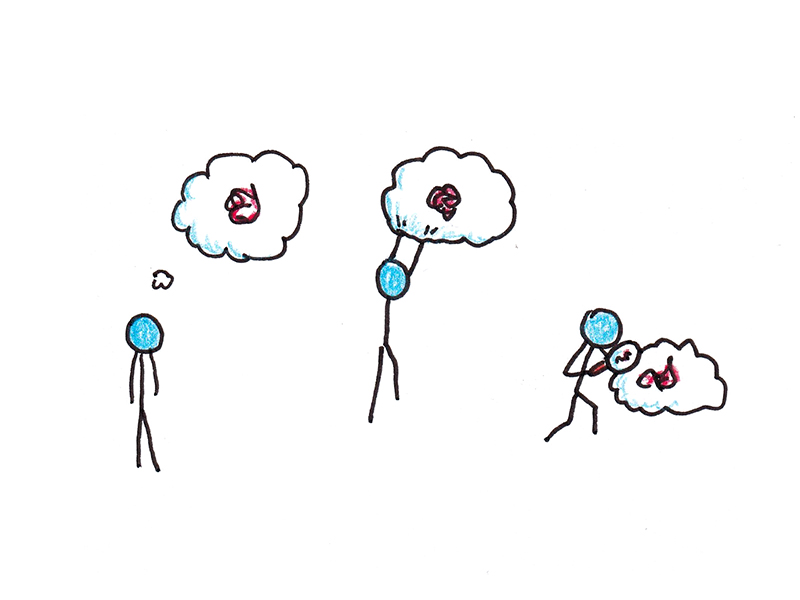

Cognitive behavioral therapy (which I review in-depth here) is the gold standard for psychotherapy for anxiety disorders. A basic tenet of this therapeutic approach is that a combination of situational factors and our background beliefs triggers automatic thoughts. If you’re stressed, those thoughts often fixate on potential dangers that are out of proportion to the actual risks. For instance, a moment of frustration with a work task may lead immediately to the thought, “I’m no good at this,” or “I’m never going to get done in time.” Those automatic thoughts trigger anxiety and further worried thinking.

One way to break this cycle of anxiety spurred by reflexive thoughts is to question the content of those thoughts. Notice a thought you’re having, and give yourself some reasons it might be true and some reasons it may not be. Ask yourself if you think it’s 100% true, 0% true, or somewhere in-between.

Questioning our reflexive thoughts can help stop irrational behaviors we often fail to interrogate. “I’m never going to pass this test, so why bother studying?” or “I only have an hour left in the day, so it doesn’t make sense to start this unpleasant task,” are probably not things we’d assent to if we gave them much thought, so we need to catch ourselves before we mindlessly accept them.

2. Treat your task as an experiment

Exposure therapy is a method developed for treating phobias that has since found wide applications in all sorts of anxiety disorders. The basic tenet is that exposure to a feared situation—without experiencing significant harm—tends to reduce the intensity of emotional reactions in the future.

This can be relevant when the work itself is what is stressing you out. You may anticipate a negative reaction to your work, “My boss isn’t going to think I did a good job,” or you may worry about your ability to handle the task, “What if I make a terrible mistake?” In these cases, pushing forward with the work itself can often be an internal struggle since you’re dealing with both the difficulties of the task and the difficulties of managing the emotions stirred up by the task. One strategy that can help is reframing parts of the task as an experiment. In this case, the goal isn’t to achieve a particular result; rather it’s to see what will happen if we try. If we feel incompetent, we might start working on a task to test that belief. If we worry about a negative reaction, we might ask for preliminary feedback when we don’t think our work is good enough yet.

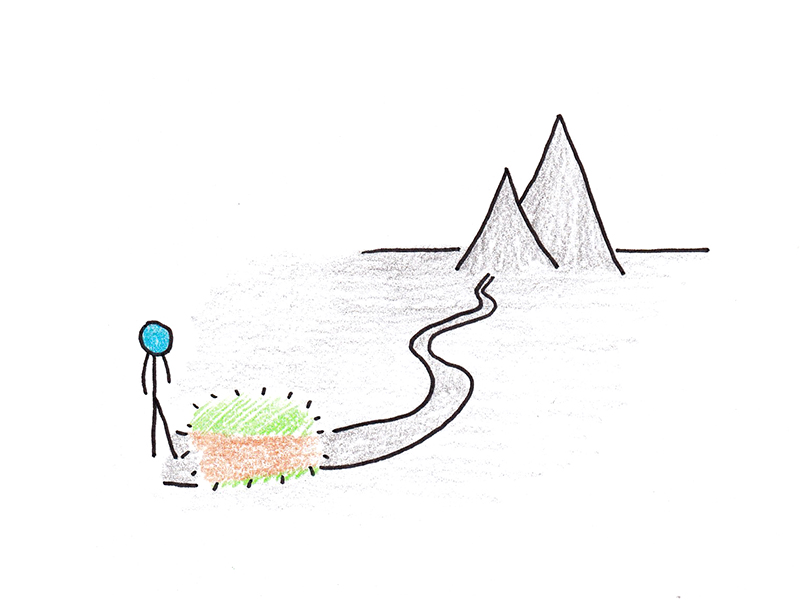

3. Make completing the next step your entire goal

Recently, mindfulness has been validated as a therapeutic treatment for anxiety. There are varying mindfulness practices, including focusing on a particular object (your breath, bodily sensations) or simply trying to notice your subjective experiences without judging or controlling them.

One takeaway from mindfulness practices is that most of our worries are future-oriented. Stress and anxiety tend to disappear when we’re focused exclusively on the present moment.

We can apply that same mindset to working when stressed. Break down the task you’re sweating over into only the next single step and make completing that step your entire focus. Deliberately try not to pay attention to any planning or problem-solving beyond that one step. Once you’ve completed that step, you can move on to the next step after it, but not until you’ve finished that one.

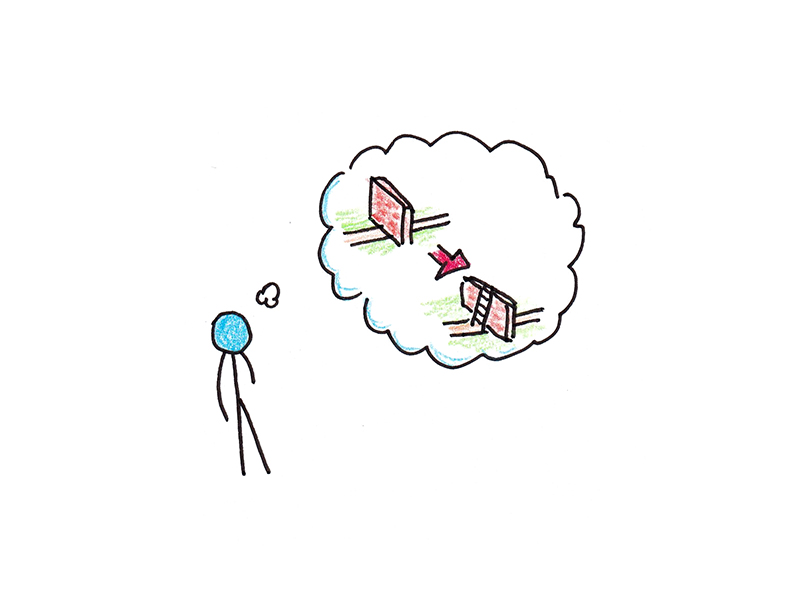

4. Use implementation intentions when planning your work week

Implementation intentions are a goal-setting technique proposed and researched by social psychologist Peter Gollwitzer. The basic notion of an implementation intention is that instead of simply setting a goal, “I want to finish my essay by Friday,” we envision scenarios where we face likely obstacles and then come up with specific intentions for how we will cope with them, “When I’m tired at the end of the day and don’t feel like writing, I’ll set a goal to finish just one sentence.”

If you have a stressful workweek ahead, visualizing the week and setting implementation intentions can overcome impulsive responses to give up or procrastinate when you face frustrations.

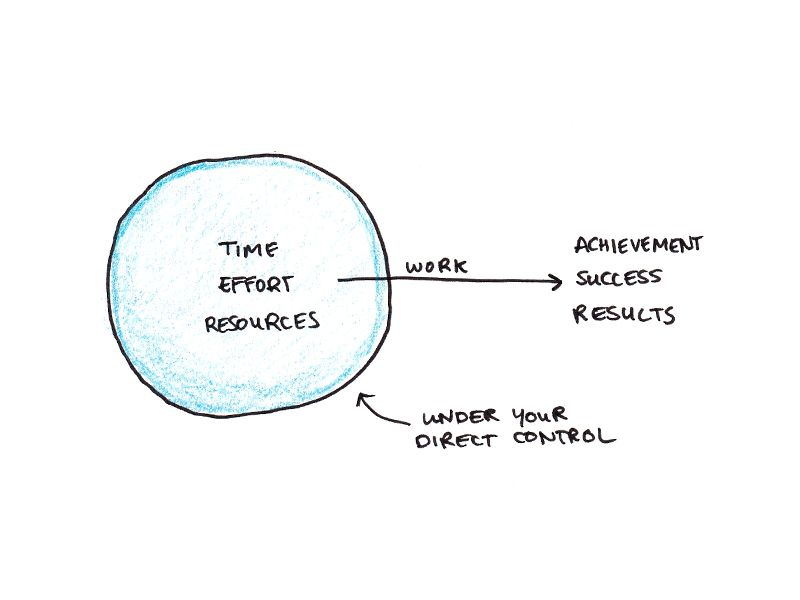

5. Reward input over output

Under normal circumstances, we tend to judge ourselves by our accomplishments. If we spend an hour and finish all our work, we feel good. If we work for an hour and get stuck, achieving nothing, we feel bad.

This can create a real bind for stressful work where success is uncertain. We might finally summon the motivation to work on a challenging task, only to get stymied for reasons outside of our control and end up feeling miserable.

The key is to shift your mindset toward input rather than output in your tasks. If you make your goal to show up and put in the time you planned to, rather than achieving a particular result, you can detach yourself from some of the worries you might have about the outcomes of your work.

When I’ve struggled with writing difficult chapters in my books, for instance, I’ve often made it a goal to give myself credit just for sitting down for my writing sessions. This way, I don’t punish myself for failing even if I end up getting stuck over how to tell a particular story or what research to include because I met my goal of showing up and doing the work.

Note: This strategy works best when there’s a lot of friction to getting work done. When the work is coming fast and easily, focusing on results can be more effective in helping you slow down and execute the tasks that matter most.

Is it a Temporary Strain or Toxic Workload?

My advice above assumes, of course, that your situation is the result of a temporary strain or irrational anxiety, not a toxic situation that you should extricate yourself from at the nearest juncture. Knowing the difference between the two can be tricky.

My rule is that a challenging situation worth sticking with is one that:

- Is aligned with your long-term values. For instance, if you are struggling in medical school but still want to be a doctor, the struggle may be worthwhile. But if you are struggling in medical school, don’t want to be a doctor, but feel like you can’t do anything else without disappointing your parents, the struggle probably isn’t worth it.

- Involves people who treat you with respect. If the stress is due to employers or coworkers who are not respectful, trying to diminish stress may be less helpful than directly tackling the relationship in question—either getting it into a healthier state, or finding an exit ramp if the personalities involved are unwilling to adjust.

- Is anticipated to be temporary, rather than perpetual. If a situation is temporarily stressful, such as a short-term heightened workload, insufficient experience or sudden changes, then enduring through stress is often good. In contrast, if the stress becomes chronic, even when you’ve had a chance to adapt to the changes, it may be better to look elsewhere.

Our emotions affect our productivity, but how we handle those emotions is vital. Focusing when stressed may be challenging, but cultivating persistence under strain can be a powerful asset.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.