I’ve long been a fan of language learning. In college, I studied abroad for a year to learn French. Later, I spent a year traveling with a friend picking up Spanish, Portuguese, Mandarin Chinese and some Korean. I’ve learned a bit of my wife’s native language, Macedonian, and worked through some phrasebooks while traveling in Italy and Japan.

With advances in artificial intelligence and machine translation, it’s easy to wonder whether language learning still makes sense.

My answer is: For monolinguals who live within their own country and have no desire to travel or immerse themselves in a foreign culture—probably not. But I don’t think the cost-benefit calculation has changed much for those who want to or do spend considerable time in another culture. Automatic translators may help on a weekend stop in Paris, but they’re not an effective substitute for learning the language if you plan to live dans l’Hexagone.

Instead, I’d like to consider a different question. For a linguistic enthusiast, does it make more sense to learn one language or many?

Speaking Multiple Languages is Comparatively Overrated

Given my own investments in learning multiple languages, I’m going to play devil’s advocate today and argue why, despite the seeming appeal of speaking several tongues, most people are probably better off sticking to fewer.

1. Each language needs maintenance.

Benny Lewis was one of my first introductions to the online polyglot community, a group of people who are dedicated to learning multiple languages. Benny speaks about a dozen languages, but some people have gained a degree of fluency in thirty or more.

When I first met Benny, he had recently finished a stint in (I believe) Poland and had picked up some Polish over his three-month stay. I congratulated him on adding a new language to his repertoire, to which he replied, “Oh, but I’m not going to maintain it.”

To me, this seemed wild! How could he spend months learning a language and be so flippant about maintaining it?

Now, I realize I was being naive. Maintaining a language is hard work. Maintaining multiple languages is a lot of hard work.

Languages are enormously dependent on fluency, but fluency is the first thing that degrades if you aren’t using a language—even after intensive practice. Extensive practice over decades can help with this, as can intensive practice on high-frequency words. But the tip-of-the-tongue feeling that is an infrequent nuisance for native speakers becomes a source of constant frustration if you don’t practice regularly.

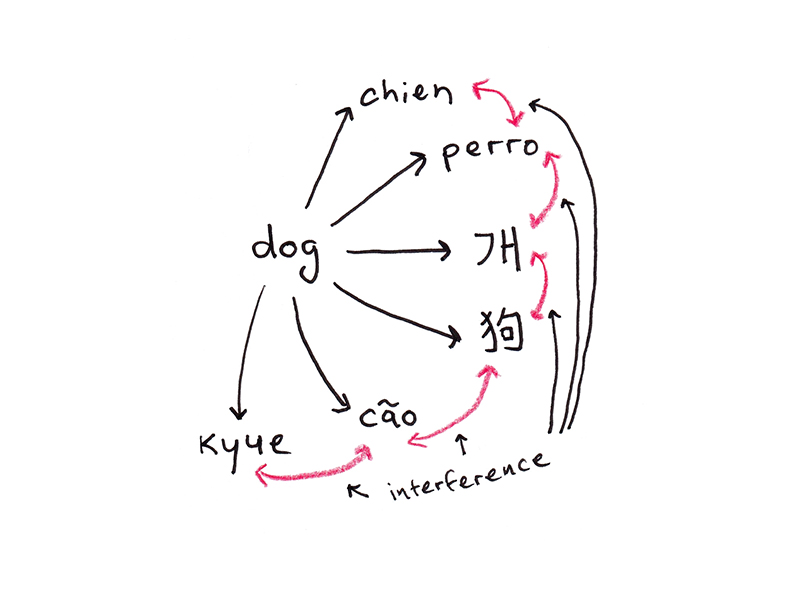

Maintaining multiple languages has all the difficulties of maintaining each language on its own, as well as adding the problem of interference.

To oversimplify, language learning is largely a process of building associations between an intended meaning and a linguistic form that communicates that meaning. But one of the most well-studied phenomena in memory research is that when you associate one input with two different responses (for example, apple is both “pomme” and “manzana”), it creates a lot of interference.

Interference tends to be more severe with speaking and writing than with listening or reading because language → meaning is a consistent mapping, whereas meaning → language varies depending on which language you’re trying to produce. Interference can be overcome through regular practice that alternates between languages. However, this type of practice significantly increases workload.

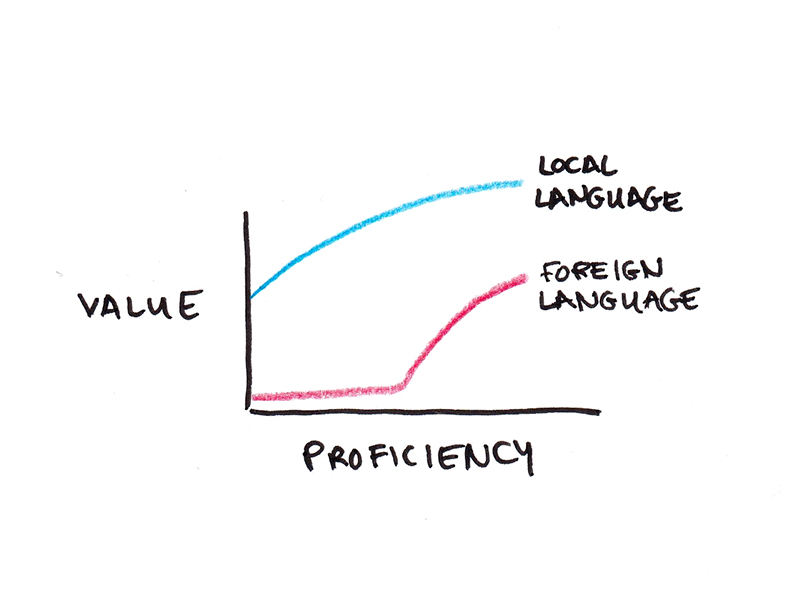

2. Lower proficiency is less valuable in non-immersive contexts.

All else being equal, the same amount of time split among several languages will result in a lower proficiency than if that time was invested in one.

This means that the choice isn’t usually between speaking one language perfectly or several languages perfectly; it’s between speaking one language better or multiple languages worse. My desire to learn multiple languages has definitely drained energy I could have spent mastering just one.

An observation I quickly made after my language learning trips was that while speaking the local language was beneficial at almost any level of ability, speaking a foreign language had limited uses at lower ability levels. The reason is simple: if you live in an English-speaking country, almost everyone knows some English, so to communicate with someone in a different language requires you to speak that language much better than they can speak English.1

This observation applies to more than just conversational ability. While living in Spain, being able to read menus and printed instructions in Spanish (which requires a fairly low level of fluency) is enormously useful. In contrast, outside of Spain, the situations that benefit from understanding Spanish are things like reading literature or watching international news clips—things that require a much higher level of ability to appreciate.

Now, the division of effort doesn’t imply that the division of proficiency is equal. You need to learn a relatively small set of words to move from not knowing a language to having simple conversations, but to move from intermediate to advanced levels of a language means massively expanding your vocabulary. How often words are used falls off in frequency according to a power law—with common words being used very frequently and less common words being used barely at all—but the effort needed to learn words is basically flat. Thus, going from intermediate to advanced levels of a language is much harder than getting to simple conversations from scratch.

That distinction notwithstanding, if you’re not planning on traveling frequently, knowing multiple languages is less useful at home than being more proficient in a single language.

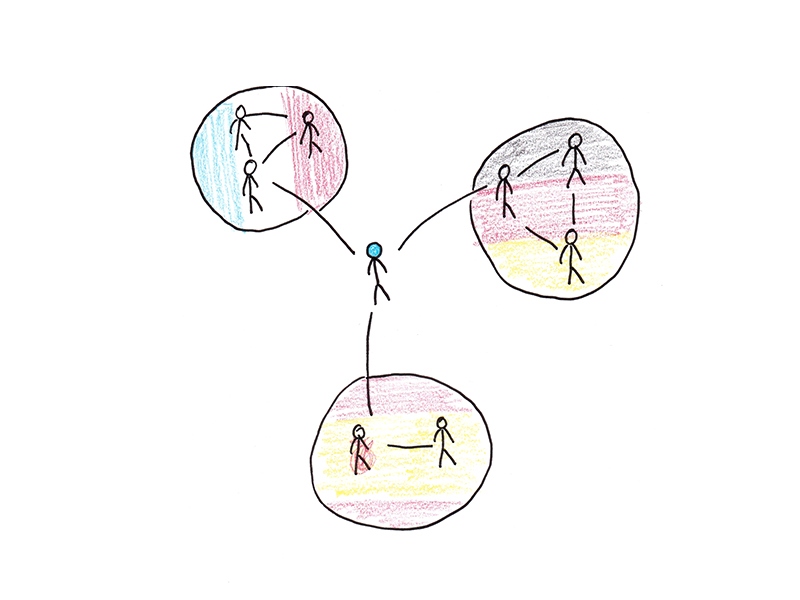

3. Multiple languages make cohesive social networks harder.

When I came back from my year abroad in France, I gravitated towards other French exchange students both because of my recent cultural experience and a desire to practice French.

However, when I came home after spending a year learning multiple languages abroad, I realized it would be much harder to do the same thing with four languages. Finding friends who speak Mandarin, Korean, Spanish or Portuguese typically requires joining four completely different social groups.

Dedicated events, like meetups for particular languages, can get around this problem somewhat, but it’s just harder to get consistent practice in multiple languages with the frequency you might achieve if you focus on a single language.

One of the key rationales for Vat and my no-English rule was that semi-monolingual social bubbles tend to form naturally. If you move to a place where you don’t have a strong grasp of the local language, it’s easiest to create a social network of people who can speak your native language. This makes it much harder to spend a significant amount of time using the language you are trying to learn.

4. The bragging rights aren’t worth it.

I remember meeting a guy in college who spoke three languages. Three! That was really cool, I thought. Later, when I was in Europe, I met people who spoke four or five. That was even cooler! So I was surprised to realize that I basically never bring up my year-long trip to learn languages when I meet people. (Obviously, this blog, which centers around my learning projects, is different!)

Some of this might be because of maintenance headaches. I haven’t spoken Korean in probably a year, and while relearning is faster than starting fresh, it’s probably going to take me at least a few sessions before I can speak it comfortably again—and bragging about speaking languages that you cannot immediately produce is pretty weak.

But the bigger part is that bragging is generally overrated. Outside of job interviews or other social contexts where listing your accomplishments is expected, conspicuously bringing up personal accomplishments is not a great way to win friends.

Thus, I think any motivation to learn multiple languages has to come from within. If you’re just doing it to seem cool, you’re probably better off getting a tattoo.

Why Might Learning Multiple Languages Be Worth It?

That something is overrated doesn’t mean it’s without value—just that it’s likely worth less than the hype.

There are good reasons for learning multiple languages, and if I had to go back and do it again, I would still do the same projects:

Each new language opens more cultures and places to you. The motivation here is the same as wanting to travel and learn one language instead of just sticking with your mother tongue. Vat and I started with wanting to do a world trip—we added language learning later on.

For short-term travel, speaking poorly is often sufficient. Even low levels of ability are often appreciated by native speakers when you’re traveling. Thus, if your main goal is to travel a lot, learning a number of languages poorly may be more useful than mastering one.

You get a better understanding of languages, in general. Metalinguistic awareness may not be your cup of tea, but I’ve found that learning multiple languages has given me a much more generalized picture of languages and learning than I had when I had only learned French.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with learning multiple languages to a basic level and focusing on making more progress in one. This was what I decided to do with Mandarin Chinese after our trip—I’ve spent a lot of time trying to get to an upper-intermediate level in Chinese while I’ve been happy to stay at a fairly low level with Korean and Portuguese.

Do you speak multiple languages? Do you think it’s better to learn one or many? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Footnotes

- I’d argue there’s an additional factor: The expected language of communication strongly shapes norms surrounding speaking. As a white person living in Canada, where the local languages are English and French, going up to a Chinese waiter in Canada and ordering unexpectedly in Chinese involves some momentary awkwardness, though I rarely experienced such awkwardness while ordering in restaurants in China.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.