Focus is hard. And in the years since I’ve started writing, it has gotten harder.

Diagnoses of ADHD (including self-diagnoses) have skyrocketed. While it’s likely that some of this is due to a lessening of stigma around mental health issues revealing what was already there, anecdotally, it appears that people are having a much harder time concentrating than they used to.

The number of people I know who struggle to finish reading a single book, or who can’t seem to stay on task for more than twenty minutes without opening their email, seems to be getting worse.

Are Smartphones Ruining Our Brains?

While technology certainly plays a role in our collective distractibility, it’s probably not the case that Google is literally making us stupider, or that we’ve lost the ability to focus. I agree with cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham, who raises his eyebrows at the idea that our fundamental brain architecture could be reshaped in this way.

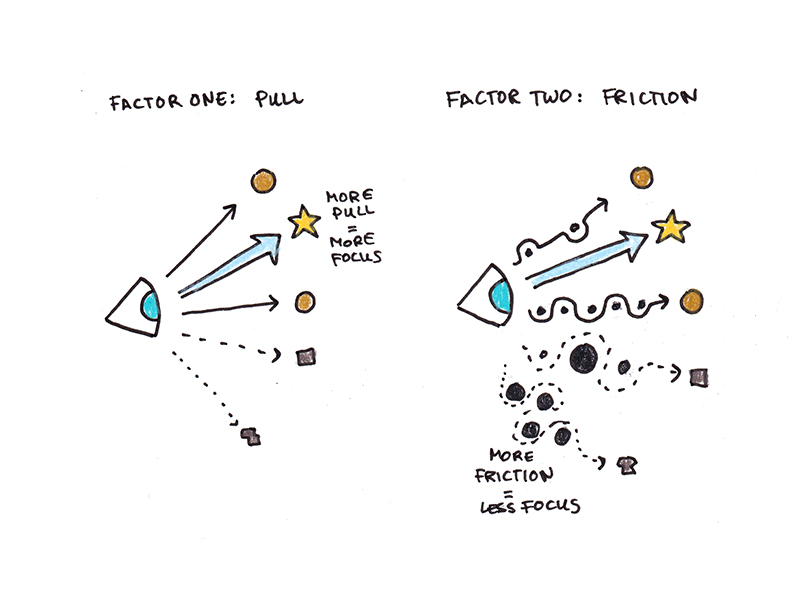

Instead, there’s a much simpler explanation for why focus is hard—and why it has gotten harder. In short, the ability to sustain attention on something is a function of two factors:

- Pull. This is how much an activity draws in and motivates us to sustain our attention. True multitasking is a myth, and our attention can only focus on one thing at a time. As a result, the pull of an activity is always defined relative to everything else we could possibly be paying attention to at this moment.

- Friction. This is how much resistance, difficulty or effort is required to sustain engagement in an activity. Too much friction, and even something that should be compelling is pushed out for easier alternatives.

These two factors help to explain why focusing has gotten so difficult lately. We’re now in an environment where strong pulls on our attention are ubiquitous, so the relative pull for reading a great book is simply too quiet compared to the pull of social media or streaming television.

Second, many of our most potent distractions have become increasingly frictionless. When I started blogging two decades ago, reading my feeds meant going to the room with my computer (I still had a desktop), turning it on (which took forever), connecting to the internet, opening my RSS feed reader, and scrolling through an uncurated list of simple headlines to decide what to read.

Had I been born two decades later, I’d instead have TikTok, which only requires taking a device out of my pocket, with whatever content *it* deems most interesting served up to me instantaneously.

“Dumb” media and old-fashioned hobbies, which haven’t altered much, have the same pull and friction that they’ve always had. But they can’t compete with the attentional candy we now encounter regularly.

How to Improve Your Ability to Focus

This two-part model of focus suggests a simple answer for how you can focus better: increase the relative pull of an activity, reduce the friction, or both. And since pull and friction are defined relative to all salient alternatives, you can achieve the same impact by reducing the pull or increasing the friction of your most tempting distractions.

Let’s consider all four possibilities:

- Increase the pull of focusing. Read more interesting books. Choose hobbies you find compelling. Join groups to integrate socializing with activities you enjoy. Measure your progress and give yourself rewards just for showing up.

- Decrease the friction of focusing. Have books always available. Have your hobbies “ready-to-go” rather than requiring lengthy setup. Stop reading books that bore you (read something else instead). Make it possible to quickly dip into the things you care about.

- Decrease the pull of distractions. Put your phone on grayscale. Switch your media consumption to RSS feeds, rather than algorithmically curated sources.

- Increase the friction of distractions. Keep your phone in a dedicated location in your house, rather than at your hip. Delete apps from your phone, so you need to log in with your computer.

A similar fourfold list of strategies can be employed for improving your focused work, not just your focused leisure: Increase the pull of deep work, decrease the pull of shallow work, decrease the friction of deep work, increase the friction of shallow work.

Shifting to a more focused life takes time and work. None of these changes are automatic, and it can take awhile for them to feel natural. But if you invest in a more focused life now, you can reap dividends for all your years to come. With sufficient time, these habits will become automatic and, sure enough, you’ll find yourself reading more books, engaging in more interesting hobbies and completing more meaningful projects.

Life of Focus, my course co-taught with Cal Newport, will begin on Monday, January 27th. If you’re interested in joining, I will be sending out registration information on Monday. I look forward to working with a dedicated group of students to help them improve their focus and achieve bigger things in 2025!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.