Last month, I shared the reading list from my month-long effort to better understand nutrition. After reading about a dozen books (including two textbooks), I frankly admit there’s a lot I still don’t know. And also, I feel like I gained a decent understanding of the current mainstream scientific perspective.

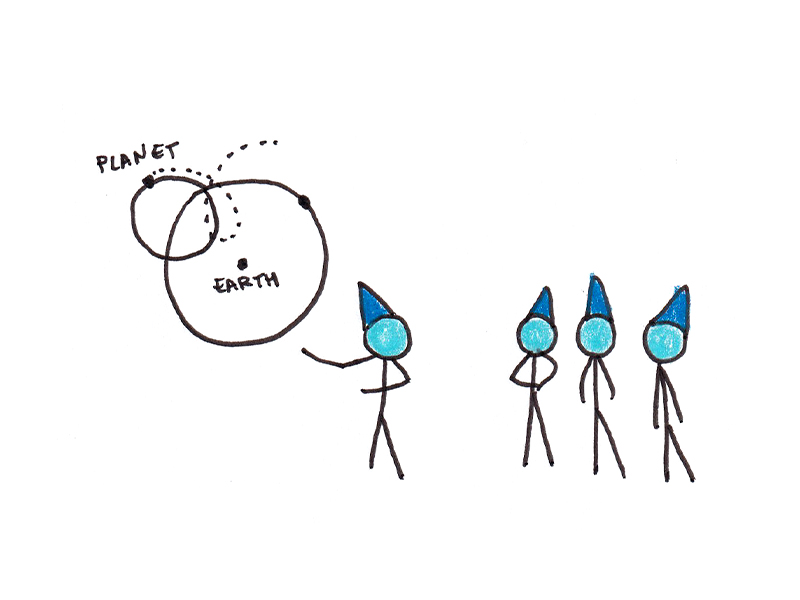

Predictably, and disappointingly, a lot of the replies I got to that article looked something like this:

“But have you read so-and-so? They wrote a book explaining why the experts are all wrong!”

It’s predictable because it’s easy to see how ideology, misinformation, and the complexity and uncertainty of doing fundamental science make nutrition one of the more contentious fields out there.

However, it’s also disappointing because none of the readers I spoke with seemed to disagree with me that their favored stance wasn’t reflected in the dominant scientific perspective—they simply thought the dominant scientific perspective was wrong.

This, to me, reflects a more fundamental disagreement I have with those readers—not one of nutritional advice1 but of how we should form beliefs in the first place.

My fundamental worldview is that:

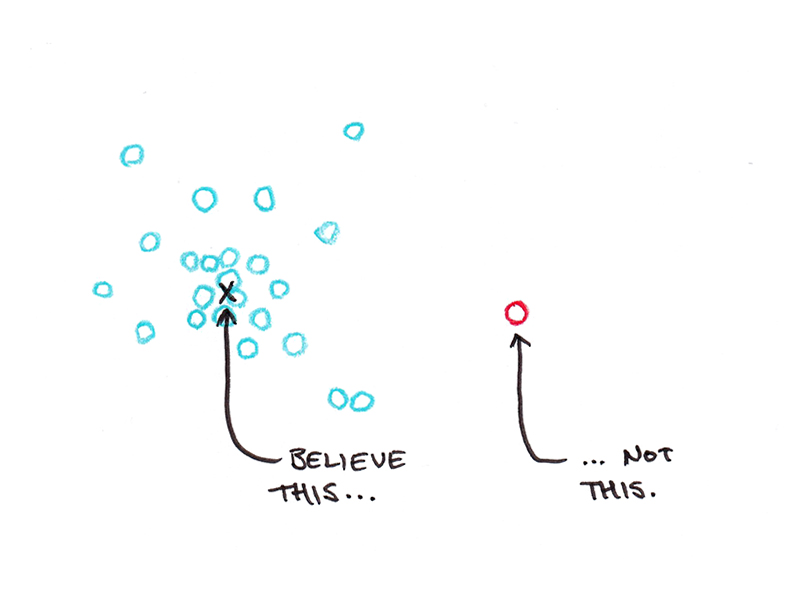

If you want to have more true beliefs, you should simply believe the experts who study the topic, most of the time.

In short, if you want to have an accurate worldview, you should avoid being a contrarian almost all of the time and simply accept whatever people who have studied a topic extensively think about it.

Why We Should Believe Experts

The rationale for defaulting to believing experts in almost all cases is simple:

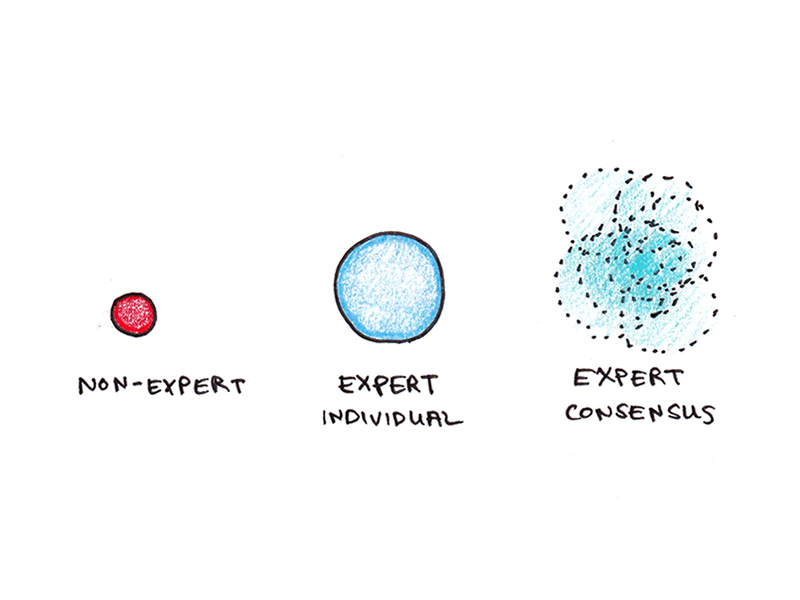

- An expert is, by definition, a smart person who knows a lot about a topic.

- The typical expert has more true opinions than the typical non-expert because they have more knowledge with which to form an opinion.

- The most common expert opinion is even more accurate than the typical expert. This is because each expert has a different subset of all available knowledge on a topic, so the average view is a better “best guess” than any individual’s opinion.

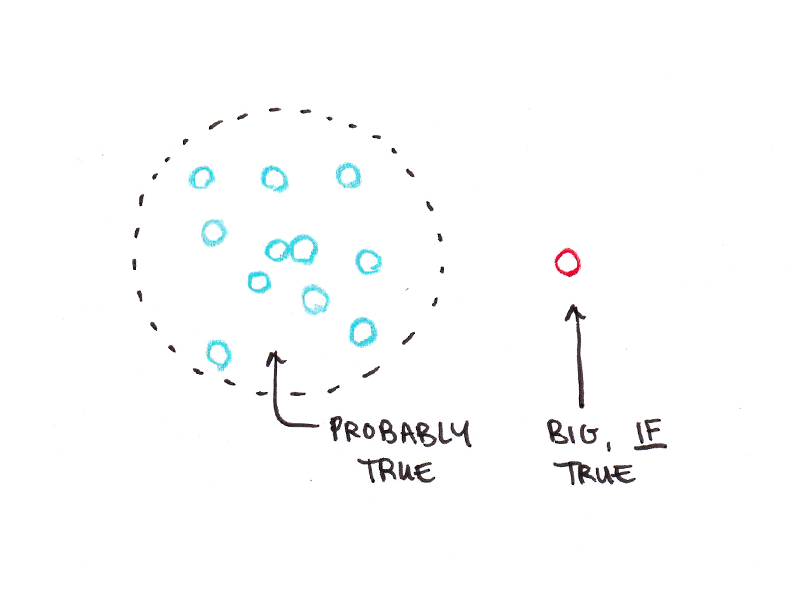

- The majority expert opinion may be wrong. But contrarian opinions are even more likely to be wrong. The value of this perspective is probabilistic: expert consensus will fail sometimes, but it fails less often than the contrarian alternative. It is therefore a strong default presumption to hold.

I forget exactly where I first heard this argument, but I find the logic difficult to reject. Experts are more accurate than non-experts. The expert consensus2 is more accurate than any particular expert.

Despite the logic of this argument, the advice simply to believe the dominant scientific viewpoint on an issue has a lot of dissenters. Indeed, even though we could easily recognize its accuracy, if a viewpoint doesn’t “feel” right, isn’t it kind of brainless to just accept whatever some group of experts tells us to think? Shouldn’t you make up your own mind and come to your own conclusions?

Objections to Simply Trusting Expertise

There are many objections to the anti-contrarian epistemology I’m supporting here, and I’d like to review a few of them. While I do think some of these arguments can be legitimate, they need be invoked carefully. Successful contrarianism is like successful gambling—possible in theory, but it frequently leads to losing your shirt.

1. “Experts ignore X.”

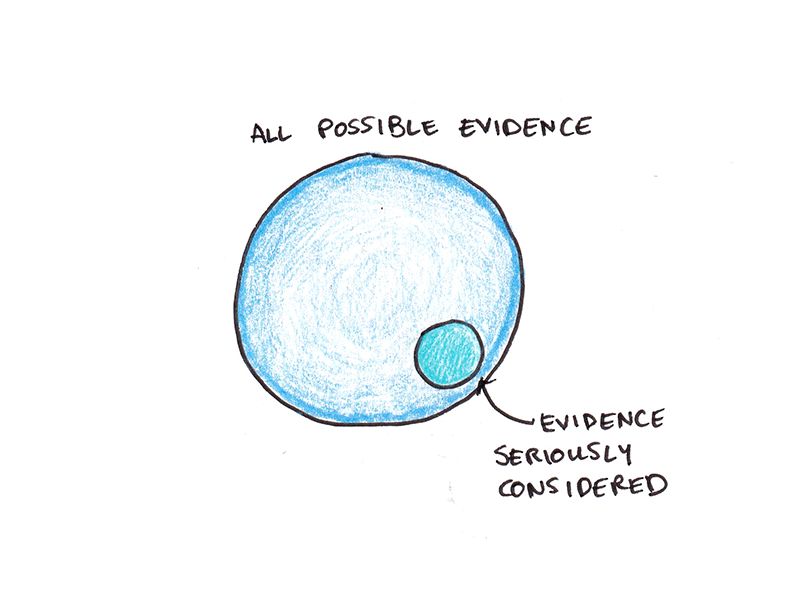

The most common cry of the skeptic is that the experts ignore valuable evidence. In this view, because the expert opinion fails to sample some part of the useful knowledge needed to form an opinion, the conclusions aren’t to be trusted.

This is undoubtedly true, but I would argue it is a virtue rather than a vice. A lot of seeming evidence isn’t reliable for forming conclusions, and simpler theories often lead to better explanations than ones that try to account for everything.

A physicist may assume an object is a perfectly rigid cube lying on a frictionless plane. A nutritionist may simplify foods into a collection of chemicals. An economist may assume people behave as rational utility-maximizing agents.

The omissions made by these models are not haphazard—experts themselves debate about which factors are important. Models and theories must necessarily be simpler than reality; a map as large as the territory it describes would be useless.

Claiming that a body of expertise is wrong because it systematically ignores some factor is simply a restatement of the contrarian claim that “factor X is important, but mainstream expert opinion says it isn’t.” In other words, this argument doesn’t work on its own. You’d need an additional explanation for why experts ignore X, even though it is evidently important.

2. “Experts are biased.”

Although my rationale for believing experts is based on the idea that experts are simply smart people who know a lot about a topic, that isn’t quite accurate. In reality, experts are social groups that carefully draw boundaries between members and non-members.

This social reality influences expertise, and anyone who has spent time with experts can attest to how much social factors influence which beliefs take root in expert communities.

If researchers are ideologically committed to a particular position, or they find certain conclusions of their research unpalatable for non-epistemic reasons, or even if they are disproportionately drawn from a group that is likely to hold strong prior beliefs, these can all be reasons to question expert conclusions.

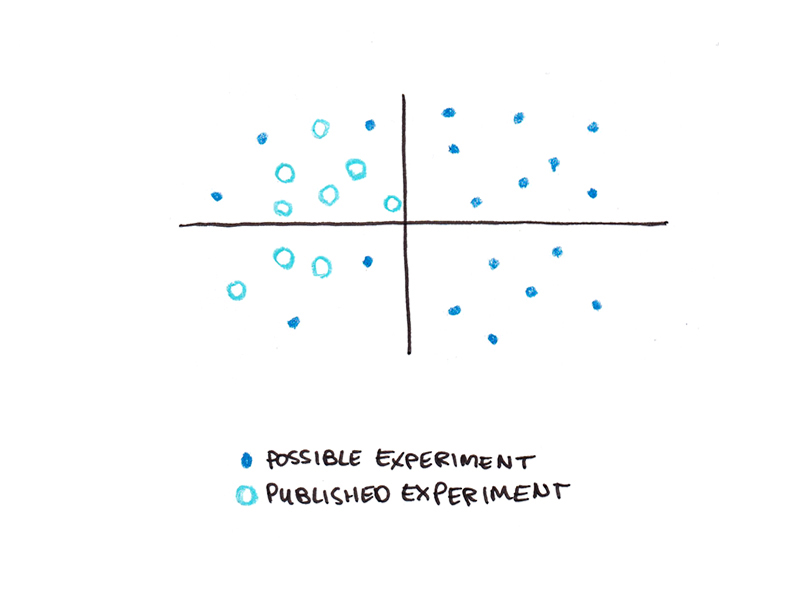

As an example, I find it difficult to wholeheartedly accept a lot of the science done by meditation or psychedelic researchers. These fields have a selection effect where many of the researchers begin with strong beliefs that those things ought to work, so there’s a greater chance of finding false positive effects for the usual reasons science can go wrong.3

However, while bias is real and potentially a ground for legitimate contrarianism, we must also turn the mirror on ourselves. We, too, have biases that predispose us to be favorable to some perspectives rather than others. Casually discarding expert opinion because of bias is the pot calling the kettle black. If you’re going to dismiss the majority opinion of a field because of bias, you need strong evidence that you yourself are more likely to be impartial—a high bar that few contrarians can surmount.

3. “Those experts are fake.”

Perhaps the biggest indictment of a field is simply to decry that the brand of expertise they practice is fake. If the knowledge the field has amassed is utter garbage, then there’s no real reason for believing any of the claims it makes.

This claim is easiest to see with the benefit of hindsight. Of course scholastics who believed in Aristotle’s four-elements theory of physics were fake. Of course doctors who used blood letting and leeches as cure-alls were fake. Of course alchemists, astrologers and fortune-tellers are fake. We see those fields, and the knowledge they accumulated, as largely worthless enterprises today—the average person would have been better off staying at home than visiting a doctor who would likely bleed them to death for a minor ailment.

Of course, the idea that economics, theoretical physics, finance, nutrition, cognitive science or social psychology are fake fields with fake expertise is popular among contrarians of all stripes. After all, if you can reject the legitimacy of experts, you can discount their consensus opinions wholesale.

I’m sympathetic to this claim. Like most people, I have my preferences for evidence and my hierarchy of fields I’m willing to believe more strongly—and those I’m more likely to roll my eyes at.

But, the argument for believing specific claims of expert opinion extends to believing in specific fields of expertise. Intellectual life doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Different groups of experts all vie for supremacy on most topics—there are many questions that are simultaneously tackled by social psychologists, economists, anthropologists and humanities scholars. If an intellectual argument clearly “wins” in the court of opinion among intelligent observers, then that field gets a larger share of the intellectual marketplace and the less-successful intellectual group withers.

Indeed, the reason it’s easier to point to past groups of experts as being clearly fake is because their paradigms did not survive the intellectual evolutionary process. Alchemy was outcompeted by chemistry. Aristotle’s theory was outcompeted by Newton’s. Modern evidence-based medicine outcompeted bloodletting and folk remedies.

In short, the rationale for accepting the legitimacy of a field are the same as the rationales for accepting a specific claim made within a field: If there were a better, more intellectually satisfying approach, the likelihood is that the better approach would dominate the current paradigm—from another community of experts if not from within.

4. “Trusting experts is intellectually lazy. You should review the evidence and come to your own conclusions.”

A final objection doesn’t rest on the weakness of expert opinion, rather on the supposed intellectual vice that simply trusting experts creates. In this view, being the kind of person who follows along with the mainstream consensus is cowardly and lazy: you should bravely think for yourself—even if you sometimes get the wrong answer.

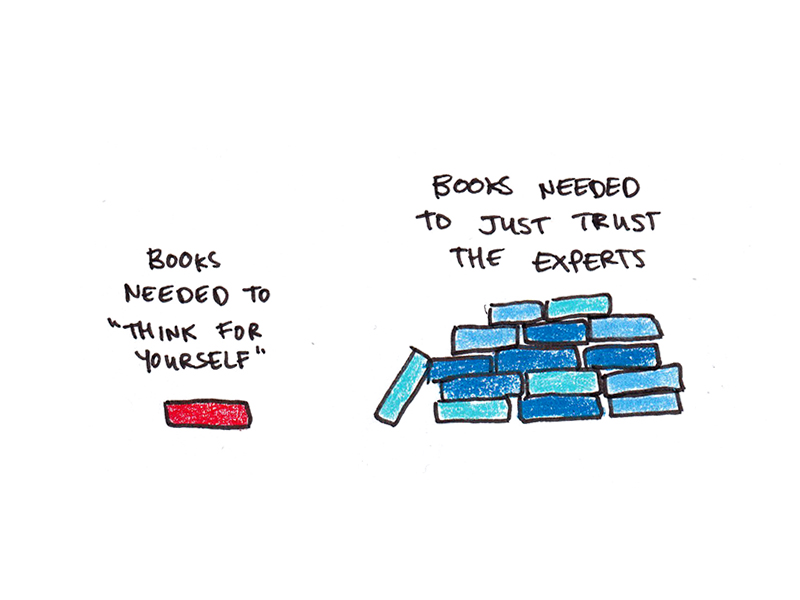

But this, to me, is a fundamental misconception. Trusting expertise is not an intellectually simple task. It takes enormous work to bring your worldview even partly in line with what experts think. Deep understanding requires you to review much of the knowledge that experts possess—hardly a task for the intellectually lazy.

Instead, it’s typically the reflexive contrarians who are intellectually lazy. They would prefer to read one flashy book that supports a worldview they are already predisposed to believe rather than wade through multiple dense textbooks that slowly build the consensus perspective.

Simply parroting the conclusions of experts is not enough. To really understand an expert conclusion, you need to develop for yourself the mental models used to generate it. That’s hard work. It’s why getting an advanced degree in a field takes so long—mastering the tools and models needed to accurately simulate the expert opinion in a wide range of scenarios within a single field takes years, and that must happen before the student can do their own meaningful work in that field.

Truly smart contrarianism not only has to articulate an opposing view, but provide a deep explanation for why that viewpoint is not widely accepted by other smart people with similar knowledge. Few experts in a given field ever reach this position, never mind casual readers commenting on a topic outside of their specialty.

Some Final, Moderating Factors

My original advice was:

If you want to have more true beliefs, you should simply believe the experts who study the topic, most of the time.

I would add a few moderating factors to that generalization:

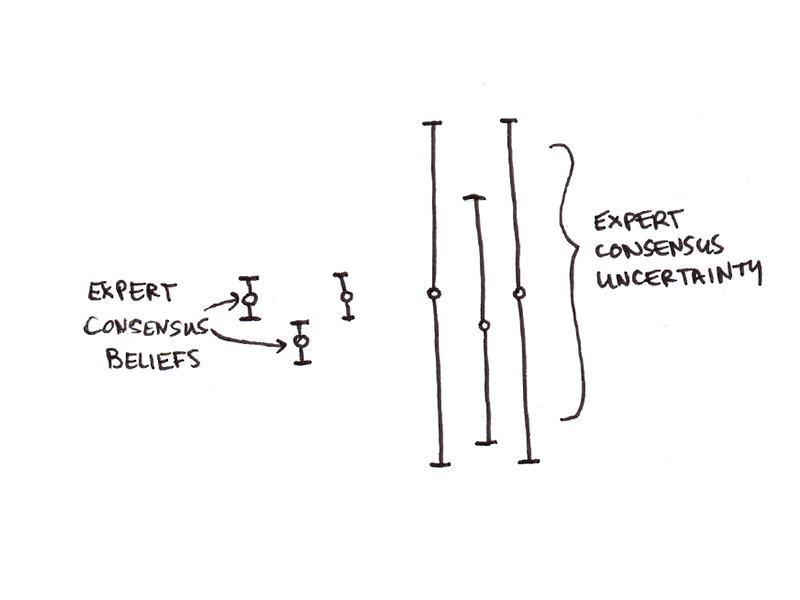

1. Experts can tell you what to believe—not how strongly to believe it.

The quality of evidence used to form expert beliefs varies widely. Despite this, experts, on the whole, are highly confident of their own opinions. Since making decisions in life depends on not only what the “best guess” beliefs are, but how likely they are to be correct, this lack of calibration is a problem for my simple model of trusting experts.

I have much more faith in basic physics than basic nutrition, for instance. I would be extremely surprised if the principles of quantum mechanics turned out to be wrong, but it wouldn’t shock me if nutritional researchers flip-flopped on the link between saturated fat and heart disease.

This lack of confidence calibration means that while it’s not usually justified to say, “the experts are all wrong, you should believe X instead,” it’s not always incorrect to say, “the experts are wrong, you shouldn’t have any opinion on X.” Skepticism of the expert view in shaky fields is consistent with the position I’m advocating for, even if true skepticism (rather than ardent belief in even more dubious propositions) is quite rare.

2. If your goal isn’t to maximize true beliefs, contrarianism can be justified.

Somewhat ironically, the individual experts aren’t necessarily incentivized to maximize the truth value of their beliefs. Expert consensus is a kind of smudgy, bland version of a particular worldview; it’s what’s left after averaging out of all sorts of unique or unusual perspectives.

In contrast, a scientist or pundit aims not just to be right about the stuff everyone already agrees on, but to be surprisingly correct—to hold a belief that later turns out to be perceived as more plausible, thus changing the consensus viewpoint.

Indeed, this may even be a good thing. An intellectual environment where all experts followed my “just trust the experts” maxim would result in excessive conformity of opinion, making bias more likely. We should want to live in a world where experts don’t agree, and instead debate each other, as this raises the average quality of their opinions.4

An analogy is investing. The average investor is better off putting their money in a low-cost index fund rather than picking stocks. Most investors (including professionals) fail to beat the market consistently. And yet, we do want at least some amount of (mostly deluded) contrarians trying to actively beat the market, since it is this very activity that determines values in the market.

Final Thoughts

While I first heard this argument for believing expertise ages ago, I don’t think its logic alone is what made me attempt to follow it more rigorously in my life.

Instead, it’s the experience of having been persuaded by a contrarian expert, being fully convinced and, years later, being dissuaded from those original views as I encountered more evidence. And unlike the boy who touched the fire, it took being burned more than a few times before I developed the reflex.

While I doubt this argument will bring any dyed-in-the-wool contrarians or conspiracy theorists to my worldview, I do hope it will nudge a few people into giving more weight to the dominant expert perspective, and a bit less weight to the voices of persuasive-sounding contrarians.

Because, ultimately, having true beliefs does matter. Your beliefs inform how you invest, eat, build your career, raise your kids and take care of your health. And if your fundamental worldview isn’t optimized for gathering true beliefs, you’re bound to make mistakes.

Footnotes

- Which, I’ll admit, any factual assertion about nutritional advice is something I only hold loosely.

- Or, if no consensus exists, then the viewpoint which would win a plurality of votes, were there to be an election.

- The opposite is also true: If people who have an ideological incentive to find a particular answer struggle to find it, that’s probably strong evidence for a null conclusion. This was my takeaway on the research on cognitive training, which has had disappointing results despite being researched by many hopeful enthusiasts.

- There is certainly a tension here with my advice. I recognize the value of believing experts, and I also recognize that if this is all I do, my work will probably fail to have much lasting intellectual value. I need to adopt at least a mild degree of contrarianism in my work, or I’ll risk being irrelevant.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.