My dad, who taught elementary school for thirty seven years, once had a kid in his class who would always interrupt the class saying, “I know that already!”

It was doubly annoying, he told me, because this kid clearly did not know it already. He was near the bottom of the class, and could probably have learned more if he had just sat and listened.

It’s an amusing story, but how many of us are acting like this kid, saying, “I know that already,” when we really ought to listen?

Why You Don’t “Know That Already”

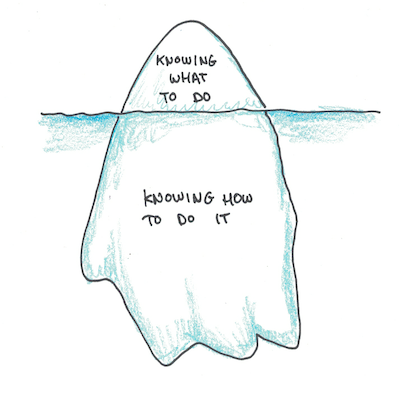

A sentiment I’ve heard expressed often is that “I already know what to do, I just don’t do it.” The idea being that you don’t need more education, you just need to do the things you already know.

In a certain sense this is probably true. Eat plenty of veggies and not too much junk food. Save for retirement. Go to sleep early. Don’t yell at your spouse. These aren’t so surprising.

You know these things, but you probably slip on them more often than you’d like. Therefore, it makes sense that you might say you know these things already, and the disconnect is simply willpower, motivation or both.

Doing is a Kind of Knowing

Where I disagree with this common sentiment is that being able to do things is a kind of knowing. Being able to follow your plans, stick to habits, achieve hard goals and maintain your cool in tense situations are learnable skills.

Therefore, while a failure to make savings or eat your broccoli may not be because you don’t understand nutrition or finance, they still represent a gap in your knowledge. You don’t know how to do the things you need to.

To appreciate this, you have to see willpower, motivation and behavior as themselves being complex systems you don’t fully understand. Seen from this way, the fact that you don’t save for retirement, even though you really should, is because of a lack of knowledge. The knowledge you’re lacking isn’t that you’re unaware that saving is important, but that you don’t know how to make that change happen in your life.

How Do You Learn to Manage Yourself?

Getting this kind of knowing is, like learning all things, a dose of theory and whole lotta practice.

The theory itself isn’t too hard. Habits, goal-setting, motivation, confidence, self-conception, these are all topics you could probably understand well enough after reading 10-20 books. If you’re not sure where to start, here’s a few to get going:

The practice is more work. It’s not just that self-improvement is hard work, which of course, it is. Rather, the specific difficulty is the capacity for self-reflection. It’s not enough to just go out and do things—you need to observe what you’re doing and track the results.

Here are some questions to reflect upon:

- When you have to work on something unpleasant, how do you still put in the time?

- When you need to sustain effort on something for years, without falter, how do you keep it up?

- How do you make progress when you feel tired, or even exhausted, most of the time from your regular life?

- How often do you start projects, only to get distracted and change targets a few weeks or months later?

These are just a few, but if you don’t have concrete systems in place for handling these common issues, I’d argue that you really can’t say that you, “know it already.”

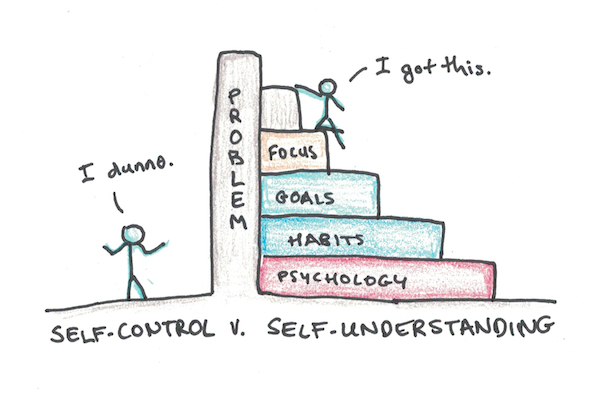

Reframing Self-Control Problems as Self-Understanding Problems

There’s another, side-benefit to all this. I find that when you reframe a problem of self-control as one of not fully understanding yourself, it’s a lot easier to move forward.

Say you’re trying to exercise and you haven’t been going much. If that’s a “willpower” or “motivation” problem, what are you going to do about that? Probably nothing. If saying to yourself “Just do it!” doesn’t work, what then?

In contrast, if you view your problem with exercise as not having the right system to make it an automatic habit, all of a sudden you can ask more interesting questions. Why has my habit been hard to sustain? What could make it last longer in the future? What things have I been doing that make it harder to keep up?

I find that a similar leap is often responsible for success and failure with learning as well. If you see studying as mostly a self-control issue, rather than a complex system of both the cognitive acts of learning and habits and behaviors that go into making those things happen, you’ll spend most of your time beating yourself up for “not studying hard enough.”

The solution, therefore, is to admit you don’t actually know it already. That there are, in fact, many things you don’t know or understand about yourself. You can get much better results, if you only choose to learn and listen.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.