What makes someone an expert? The word is often used to refer to two different types of people:

- A skilled practitioner. Someone who has personally achieved a high level of performance in a given field.

- A knowledgeable theorist. Someone who has studied, argued, researched and theorized about how a field works.

In short, doers and thinkers.

This distinction tends to hold across many domains. An excellent pilot, or an expert in aviation. A crack coder, or a computer scientist. Legendary investor Warren Buffett, or Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman.

In some domains, these tend to be one-in-the-same. I don’t think it makes sense to talk about physics experts being split between doing and thinking. Doers in physics are also thinkers. Similarly, some fields lack enough theory to have thinkers—an expert sushi chef who doesn’t make sushi is a self-contradiction.

If you’re getting advice, who should you listen to: doers or thinkers? I’d like to argue that this question has a more interesting answer than it might first appear. If you can take the best parts of both, you’ll make better decisions than following only one kind.

What Separates Doers from Thinkers

Although clear examples of doing-vs-thinking exist in many domains, most examples aren’t clear cut.

Expert thinkers usually require at least some doing to properly understand their field. Linguists typically learn other languages, if only to understand their own better. They may not be the most prolific polyglots, but they can typically speak something other than English.

Similarly, expert doers usually require some theory to be proficient. An expert surgeon that doesn’t know anything about medicine is a quack.

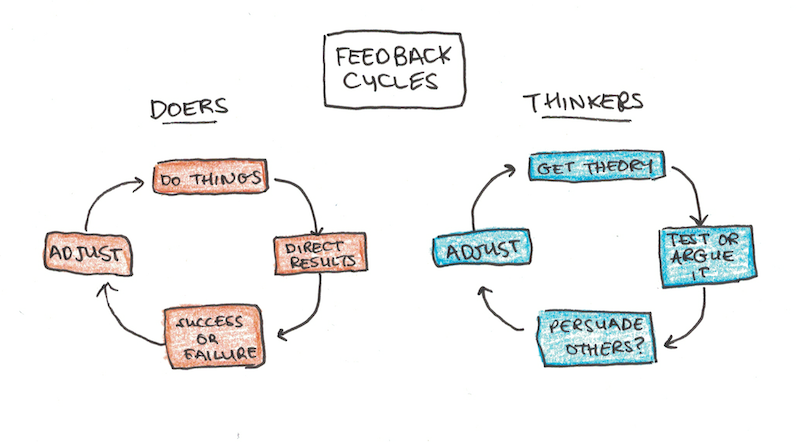

Therefore, I don’t think it’s useful to divide up these experts based on how much they do vs think. Instead, I think the key distinction is what kind of feedback they get from their environment.

Doing VS Thinking Environments

Doers live in a world that rewards them for performance. Entrepreneurs are graded by the market, not a teacher. Surgeons succeed and fail on their ability to save lives. A pilot that crashes isn’t going to be an expert for very long.

Thinkers live in a world that rewards them for having high-quality ideas and theories, as judged by their peers. Economists are prestigious when they can make sophisticated arguments using math, models and data to make their point. Medical researchers get acclaim when they can demonstrate the efficacy of different treatments from experiments.

It’s this difference, more than the actual amount of time spent doing vs thinking, that characterizes so much of the difference between doers and thinkers.

Doers are the “Real” Experts… Or Are They?

When I first posed this problem on Twitter, I got a number of replies favoring doers over thinkers, in general. Doers actually have skin in the game, the reasoning goes, so why ever trust someone who earns esteem without actually getting their hands dirty?

In practice, however, there are plenty of situations where we trust thinkers over doers, as we should:

- I’d much rather listen to a doctor, who hasn’t had cancer, about which treatment to pursue than hear about a cancer survivor’s recommended medicine.

- I want my NASA rocket engineers to have PhD’s, not just a lot of experience setting off explosions in their backyard.

- I’ll trust my food supplement choices to a nutritionist, not just some guy at my gym who is really buff.

Since we all accept that there are situations where trusting an expert with minimal direct experience makes sense, I think the more interesting question is why thinkers sometimes beat doers for advice. Also, if we can understand some of the factors at play, it might help sort out who to listen to when the choice isn’t so obvious.

Comparing Doers and Thinkers: Whom Should You Trust?

Doing and thinking are different skills. It’s possible to be a great practitioner and lack clear theories about how success works. This happens more often than you’d think.

Consider using a can opener. You’re probably already an expert practitioner in can openers, and you’ve probably opened thousands of cans in your lifetime. Yet, if I asked you if you could explain how a can opener works, could you?

The difficulty you’re experiencing is known as the illusion of explanatory depth. Just having a lot of experience with something doesn’t necessarily make you great at understanding how it works. In fact, in one experiment researchers were able to get participants to steadily improve their design of a mechanism—yet nobody had the correct theory for why it worked.?*?

This is why we need separate theorists in the first place, because simply doing a lot isn’t guaranteed to generate the right abstract-level theory about how it works.

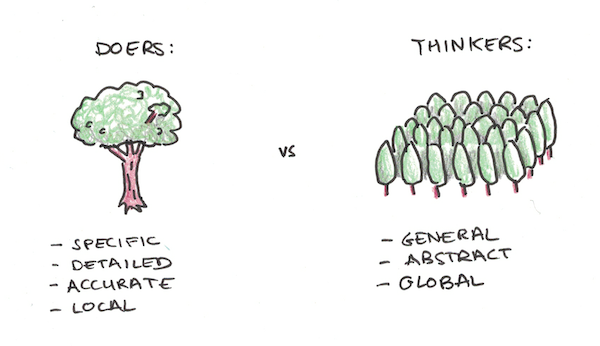

Why Doers Can Sometimes Give Bad Advice

There are many times when being good at something directly doesn’t yield useful advice:

- Experience the tree, miss the forest. Successful entrepreneurs start one company, but often give advice for all companies. Just because you know every detail of a single tree doesn’t mean you understand how the forest works.

- Can’t separate successful strategy from background context. All success is a combination of both the methods a person used to succeed (which you can too) as well as background factors that are unique. Teasing these apart isn’t easy, and sometimes we do it wrong.

- They don’t remember (or understand) their own success. In Cal Newport’s book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, he discusses how Steve Jobs advice differed dramatically from the path Jobs actually took. We’re always editing our own autobiographies, sometimes to the detriment of those who follow our lead.

Why Listening to Thinkers Can Backfire

This isn’t to say that thinkers are immune from giving terrible advice:

- Bullshit is higher when success isn’t tethered to the real world. If you only need to sound impressive, not be impressive, then it’s easier to have theories and ideas become unhinged from the real world.

- Theories can be true and also irrelevant. David Chapman tweets here about how many fields claim wide intellectual territory, but mostly debate highly contrived minutia in practice. Most problems are wicked, which makes them unsuitable for theorizing, and thus many thinkers prefer to retreat elsewhere.

- Prestige often substitutes for knowledge. According to Robin Hanson, we often seek advice not to get useful ideas, but to affiliate with high-status people. If thinkers are seen as especially prestigious this can add a veneer of acceptability to their advice which doesn’t withstand actual practice.

Combining the Best of Thinkers and Doers (and Avoiding the Worst)

The best approach is to combine both thinkers and doers, to trade-off their weaknesses for each other.

The theories of thinkers tend to be better than those of doers. Therefore, if I’m trying to think abstractly, I tend to side more with ideas from scientists, academics and people who have to defend their ideas for a living rather than some guy who was successful once.

Detailed advice, however, tends to be better from doers. Specific steps, tactics and strategies tend to be better when they come from a practitioner, as this person hasn’t only calibrated against what works, but also what’s relevant.

If I were to apply these two rules of thumb to something like health, that might mean I’d want to get my general sense on which diets are healthy, what kind of exercise to do and how much from an academic source (thinkers), but I’d want the specific plan, how to make it stick in practice, motivation tips and detailed strategy from someone who is super fit (doers).

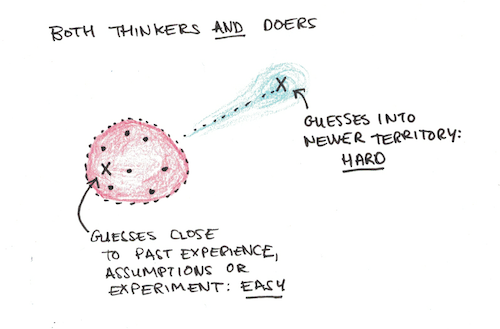

Advice from thinkers tends to be worse the further it leaves the assumptions and evidence backing up their theories. Advice from doers tends to be worse the further it leaves their personal experience. In both cases, better advice is mostly interpolation, whereas dubious advice is mostly extrapolation.

What do you think? Who do you trust to give you advice? Why do you trust those people compared to other people who offer suggestions on a topic? Share your thoughts in the comments.

-

?*?Derex, Maxime, Jean-François Bonnefon, Robert Boyd, and Alex Mesoudi. “Causal understanding is not necessary for the improvement of culturally evolving technology.” Nature human behaviour 3, no. 5 (2019): 446.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.