Could productivity be a bad thing?

I had a podcast interview about Ultralearning recently where the host asked if being productive might be overrated. Working all the time, striving for ever-more efficiency, aggressive efforts to get more done, maybe chasing productivity isn’t the answer?

I couldn’t disagree more. Productivity features a lot in my writing because I believe it’s central for living and working well.

Yet, I often don’t say this explicitly. The value of productivity is so obvious to me, that I rarely articulate my assumptions about it. Today I’d like to share my vision of productivity, why it matters and why some critiques productivity are misguided.

What Productivity Isn’t

Before I explain my view of productivity, let me separate it from some related ideas it tends to get lumped in with.

Productivity is not work ethic or hustle. The decision to work a lot is a question of values—how important is work in your life? Productivity, in contrast, is about how do you accomplish the most, given how much time and energy you want to devote to work.

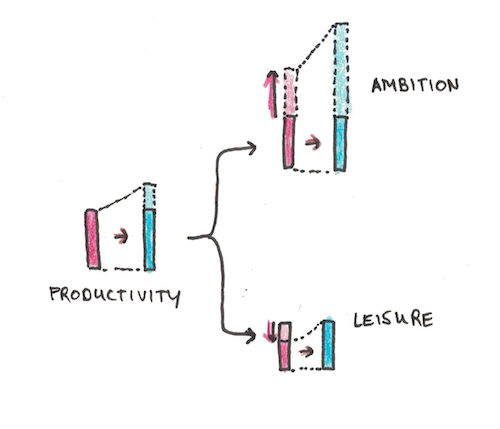

Elon Musk is productive. He’s also a workaholic. His 100+ hours of work each week pays off, but it requires an obsessive commitment.

I have another, much less famous friend, who works from home as a programmer. In his role, he only has to spend a few hours per day to keep up with his workload. This is also highly productive, but my friend chooses not to reinvest his saved time into ever-increasing ambitions.

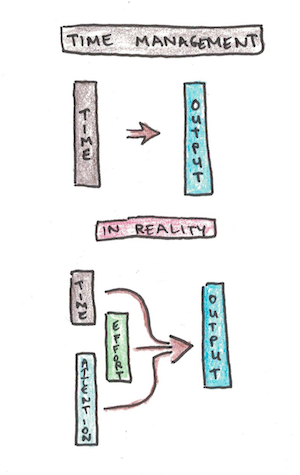

Productivity is not time management. Time management is based on the idea that the main bottleneck for accomplishing important things is the number of hours in the day. Therefore, the person who endlessly optimizes every sliver of time is the one who gets the most done.

But this approach doesn’t work. Time is nearly always more plentiful than effort. Productivity means maximizing your capacity for important work, not injecting more and more busyness.

Productivity is not just doing things that look like work. Conversations with colleagues, long walks to think, taking naps when you’re tired, vacations and hobbies can all be enormously productive, in the broader context.

What Is Productivity Then?

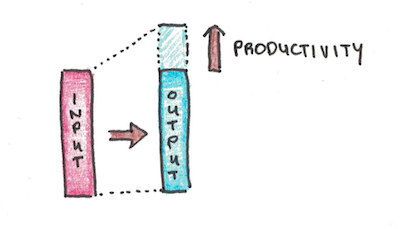

Productivity is a measure of your output divided by your input.

Output is measured by the importance of the accomplishment to your goals. A person who outputs lots of unimportant stuff is still unproductive. Importance, not sheer volume, is how output ought to be measured.

Input is measured by the time, energy and attention you have available. Sometimes this translates to speed. Other times it translates to ease or sustainability. Big impact, given your limited capacity, is the goal of productivity.

I care deeply about my productivity. But this doesn’t translate into working non-stop. In a typical day, I:

- Usually wake up without an alarm.

- Take a 20-minute nap if I need one.

- Go on walks during the day.

- Spend large chunks of time reading.

- Have conversations with colleagues and coworkers.

From a traditional perspective on work ethic, I look downright lazy. Yet, I believe my output speaks for itself. In the last decade I’ve published millions of words of essays, five books and finished big, public projects.

My situation is unusual. I have enormous flexibility in my working life. However, that flexibility itself is a result of past productivity which has generated the career I have today.

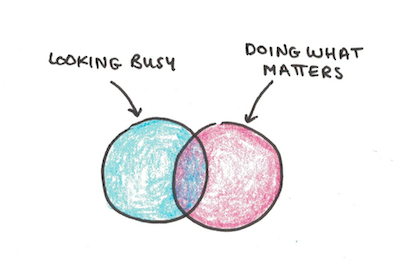

Appearing Productive VS Being Productive

Unfortunately, productivity is often judged on what it looks like you’re doing. A lot of the hustle culture and obsessive work ethic among entrepreneurs, ambitious employees and students is actually this—signaling to everyone outside that they’re serious about working hard.

This can be a cancer in an organization. Employees don’t leave the office until 9pm or later, to prove to everyone how committed they are. Meanwhile, nobody is actually getting meaningful work done. The twelfth hour of work devolves into a corporate hangout session.

This impacts entrepreneurs just as it impacts employees. I knew a guy, years ago, who was trying to bootstrap his online business. He made a big deal out of the fact that he was working 12-hour days, 7 days a week. But he was a frequent poster on message boards, discussing entrepreneurship rather than building his company.

This urge to signal is largely unconscious. Sometimes we do it to show our boss and coworkers that we’re a “team player.” Other times, we do it to quell the anxiety we have over the fact that we rarely have total control over whether we reach our goals in life.

When I defend productivity, it’s this attitude of conflating appearances over the real thing that I want to combat. Since productivity is a measure of output over input, it’s a philosophy that deliberately avoids substituting that difficult measurement with one that simply looks like you’re doing a lot of work.

What If I Can’t Always Be Productive?

The truth is, in many situations, appearing productive is a necessary evil. Your boss won’t let you take a nap, even though you’re so sleepy you can’t concentrate. Your team wants to stay up all night “brainstorming” even though you think it would be better to split off and come together when you actually have something to discuss.

Productivity is an ideal. Sometimes reality gets in the way. But it’s one thing to admit we can’t always be productive, and quite another thing to argue that productivity wasn’t worth striving for to begin with.

This vision of productivity, as well, applies to some types of work more than others. A security guard’s job, most of the time, is just to be there. In this case, output and input are largely inseparable—being really attentive for the first half of his shift won’t give him the opportunity to clock out early.

However, even if the idea of productivity isn’t universal, it can still matter for most people. For most of us, we will be evaluated on the importance of our outputs: software produced, essays written, research conducted, children taught, sales made. Better outputs for our limited inputs is a sound strategy for success in most types of work.

What is Measured and What Really Matters

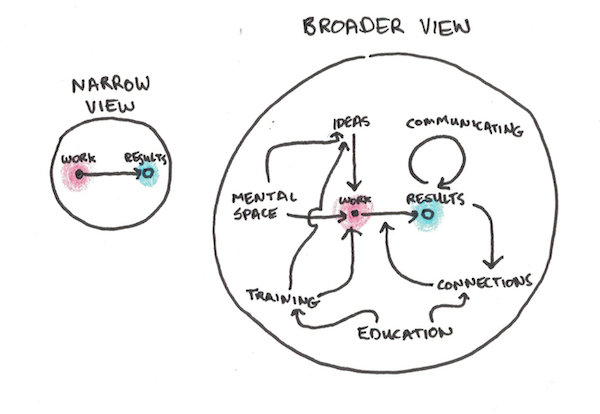

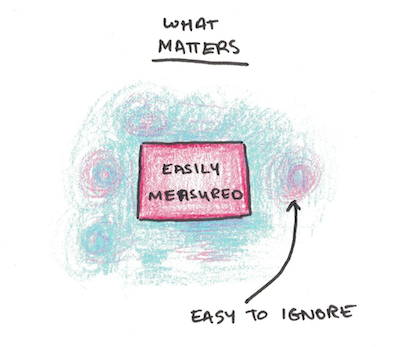

Another critique of productivity is that it’s excessively driven by short-term output over things that matter, but are harder to measure.

This, I think, was the real source of the critique my interviewer had in mind. Don’t people obsessed with productivity often neglect the hard-to-quantify-but-ultimately-essential work that goes into achievement?

As a writer, I could measure my output by the number of articles written. Optimizing for that goal, I might write continuously, never reading a book, never discussing an idea with a friend, never thinking deeply about what I do. Raw output goes up, but impact goes down.

This, however, isn’t a critique of productivity so much as it is a critique of how we count it. Just as I don’t support conflating the appearance of productivity with actual productivity, I also don’t support the short-term optimization of immediate outputs over long-term accomplishment. If this makes productivity harder to quantify so be it.

In Defense of Productivity

In the beginning of this essay, I made a contrast between being productive and being a workaholic. Productivity, as a measure of output over input, is value neutral. You can be productive even if your goal isn’t to make your entire life about work.

But that value neutrality also means that the pursuit of productivity can’t tell you what your life should be about. A set of tools can’t tell you what to build. But keep those tools sharp, and you can build whatever you’d like with them.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.