In times of difficulty, you want your efforts to matter. Not just to pass the time, but to build something that endures.

Recently, I shared why I think now is the best time to start an ultralearning project. Not in spite of the anxious time we’re living in, but because of it. Taking resolute action through uncertainty allows you to improve the things you can actually control, instead of breaking under what you cannot.

Today, I’d like to continue that theme and talk about how you can structure your efforts so that what you are learning actually matters.

Side note: Based on these ideas, my team and I started work on a new edition of Rapid Learner, with 20+ new and updated lessons. You can sign up for the waiting list here.

The Peril of Indirect Projects

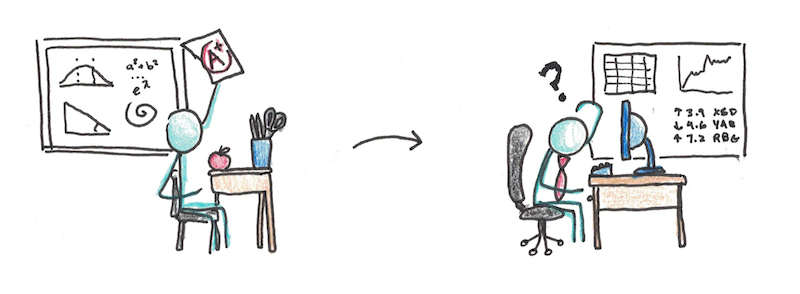

In my book, Ultralearning, I cover the research on transfer. It’s not pretty. Countless studies confirm the fact that much of what we set out to learn doesn’t actually transfer to the situations we need it. Consider just a few cases:

- In one study, students who took high-school psychology courses didn’t end up doing better at college level psychology.

- In another, those who had studied economics didn’t do better at questions of economic reasoning than those who hadn’t.

- Psychologist Howard Gardner even adds that there is now an “overwhelming body of educational research” that “students who receive honor grades in college-level physics courses are frequently unable to solve basic problems and questions encountered in a form slightly different from that on which they have been formally instructed and tested.”

All of this research explains why many of us feel like we got little out of school. Transfer—meaning the ability to actually apply and use what you learn—is a lot more elusive than it first appears.

This applies to school, certainly. But also to your own learning efforts. Choose poorly and many of your projects may not matter at all.

How Can You Avoid This Trap?

I suggest a good rule of thumb for any learning project is that the project should involve something you DO or MAKE not just something you LEARN. That may sound a little vague, so let me gives some examples:

- Don’t just learn French, aim to have conversations with people.

- Don’t just read a book on JavaScript, build a functioning website.

- Don’t just watch lectures, do practice problems from the exam.

- Don’t just read philosophy, write an essay or discuss it with someone else.

This rule won’t guarantee you’ll avoid transfer issues. But it prevents some of the more severe versions of the problem.

More Tips on Designing Your First Project

Here are a few other good rules of thumb you can follow when designing your project:

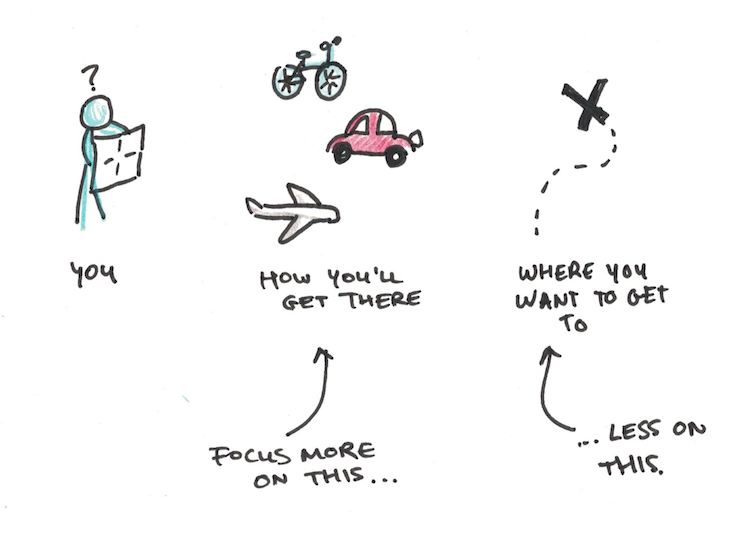

1. Inputs over outputs.

A mistake I see people make (and I’ve made myself), is to think that the important thing is picking an especially ambitious target. While it’s true that a big goal can inspire, it can also frustrate.

A better approach is to focus on how you’ll learn differently. My language learning project is a good example here: I focused not on reaching a predefined fluency goal, but of sticking to a method I knew would make progress quickly. My MIT Challenge is a counter-example, but even there I spent months planning my strategy so the choice to do it in one year wasn’t arbitrary but carefully calculated.

2. Pick your quitting time in advance.

Don’t start projects without clearly defined endpoints. For a new project, one month is a good endpoint, but two or three months also work if you have something specific in mind.

Why? Because committing to an indefinite timetable means you’ll give up as soon as things get tough. It’s much easier to say to yourself, I’m going to stick with this for one month no matter what, even if it feels too hard or something else feels more interesting.

3. Put practice first.

Some topics will require a lot of reading. Nobody got good at history, law or philosophy without first reading a lot of books. That’s okay.

But, regardless of how much reading is required, mentally give yourself priority to the practice you intend to do. Practice is the most important ingredient in building real skills, and yet it’s the easiest to pass over because it’s more difficult and often feels optional.

If you think of your project first in terms of the practice you’ll do, then reading/lectures/videos become the things you need to do first in order to get to the practice. Adopt this mindset and you’ll be less likely to engage in passive strategies that are less effective.

Today’s Homework

If you’re interested in doing something and not just reading about it, here’s what you need to do today:

- Write in the comments what you want to learn this month.

- Be sure to frame it in terms of something you want to DO or MAKE, not just LEARN.

- (If you’re a student, passing an exam counts too.)

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.