I just spent the last two months doing a deep dive trying to understand Martin Heidegger’s seminal work, Being and Time.

You probably shouldn’t read it. It’s also one of the most interesting and thought-provoking books I’ve read in the last decade. This post is my attempt to reconcile those two beliefs.

The reasons not to read Being and Time are obvious. The book is only half-finished. Of what was written, the second division is so muddled, that even after taking a companion class with dozens of hours of lectures, I still have no idea how to make sense of it.

Also, Heidegger was a Nazi.

It’s not clear how much Heidegger’s politics influence his writing. Especially around 1927 when this book was published. Still, there’s an undeniable ick factor.

However, even if you do separate Heidegger’s politics from his philosophy, he may have bigger problems. Philosopher Philippe Lemoine describes Heidegger, half-jokingly, as “The only man about whom one can truly say that being a Nazi was the least of his sins.”

Indeed, Heidegger was a major influence of postmodernist thought. You know, that philosophy that says that there is no truth, science isn’t real, all that exists are belief structures made by whomever is in charge. Heidegger didn’t say exactly those things, but his work definitely inspired later postmodern thinkers like Foucault and Derrida.

On top of all that, he’s a terrible writer. It took me a companion course, dozens of articles and books to try to make sense of it from a first reading. I can honestly say reading the Dao De Jing in Chinese was less effortful.

Given all this, why spend two months grinding through the book and why write this now? Sunk-cost fallacy in action, or is there something more?

Interesting Takeaways from a Nearly Unreadable Book

To save you the effort, there were three big ideas I got from Being and Time that were worth the price of admission:

- The concept of the background or “world”

- A rethinking of what it means to be human

- Circles of interpretation, rather than a fundamental ground

Let me try to do my best to explain each…

1. Discovering the World

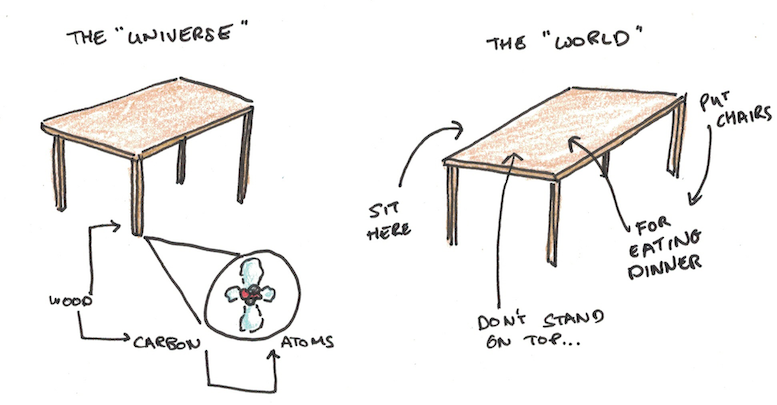

The world is not the universe. The universe is full of atoms and leptons and photons and stuff. It’s what physics studies. The world, in Heidegger jargon, in contrast, is something very human. Indeed, having one may be our defining quality.

You can see what Heidegger means by “world” when you hear expressions like “the business world” or “the world of basketball.” These expressions aren’t pointing to the electrons that make up mergers or lay-ups, but the fact that these domains are backgrounds upon which cultural practices reside.

The “business world” however, is just a part of the broader “world” we live in. The world Heidegger wants to talk about isn’t a sub-world like the world of baseball, nor even the more general world which contains these parts. Indeed, he’s not really interested in describing the contents of our world at all. Instead, he’s interested in the “worldliness of the world” or how worlds are structured, in general.

Okay, that’s a little confusing. Let’s give an example.

Consider a hammer. What is it?

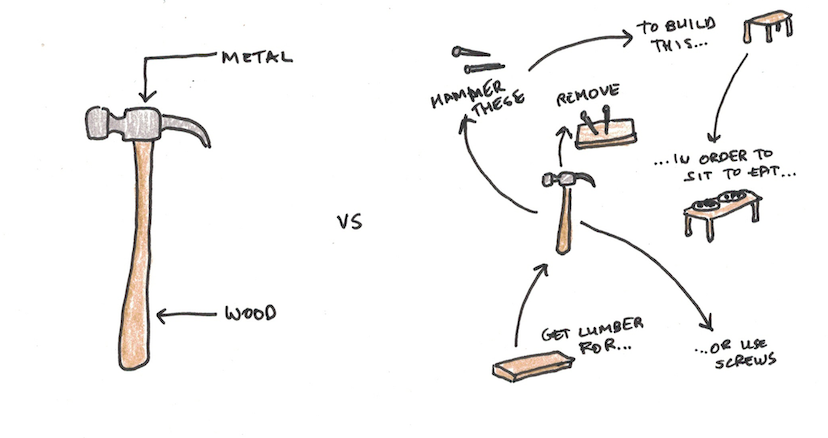

The naive view (in Heidegger’s mind at least) is to see it as a list of properties: a wooden shaft and a metal blob at the end. A slightly more sophisticated view might also include that it’s a tool or that it’s for driving nails, as if these were extra properties of the object like the wood or the metal its made of.

To Heidegger, this is totally wrong. What a hammer is, meaning, how we make sense of it, isn’t as a wooden shaft with a metal blob at the end. No, you make sense of a hammer by hammering with it.

If you have the skill for hammering, the way the hammer “shows up” for you is by being something you don’t really think about at all. Instead you’re thinking about how you need to hammer in those nails into the right spot to join the table leg to the table. To be a hammer, then, is to be something in the periphery of your attention in the context of some larger, meaningful activity.

What’s the big deal then? Well it means that you can’t make sense of a hammer, in the most basic way, without also having nails, lumber, the table you build by hammering, the practice of sitting by tables to eat and so on. In other words, a hammer, as we experience it when hammering, isn’t even a “thing” at all, but part of an interconnected nexus of equipment we know how to use. It’s via this interconnected nexus that we can glimpse at the “worldliness of the world” Heidegger wants to talk about.

Okay, but that’s dumb because obviously when you look at a hammer you can see it’s made of wood and metal. To say that isn’t what a hammer is seems obtuse.

Heidegger would respond that, of course you can also look at the hammer, it’s just that this isn’t the normal way we make sense of hammers. Indeed, he would go further and argue that, in order to just stare at a hammer and “see” that it is “really” metal and wood, we have to strip away all of the context that enables us to skillfully use a hammer.

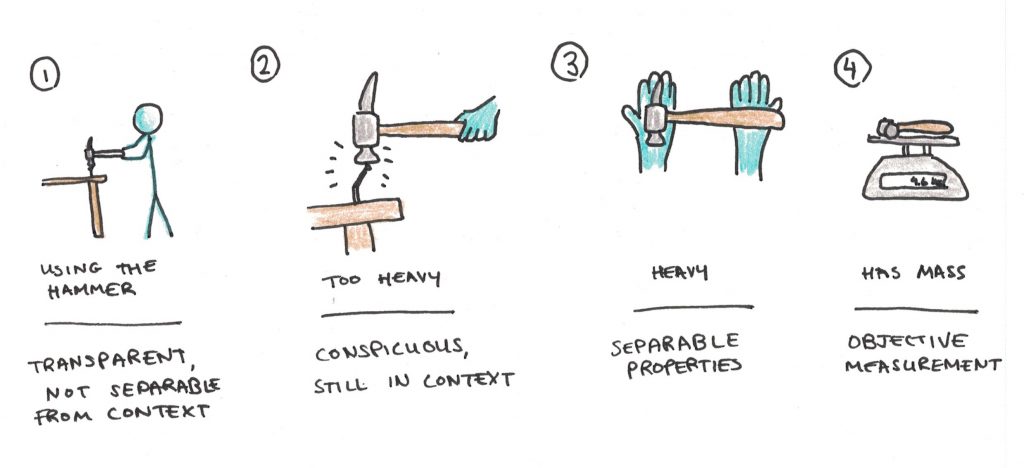

Heidegger illustrates this stripping away in a multi-step process:

- In its most basic sense, the hammer isn’t a thing at all, it’s just an invisible part of the overall task of hammering that you’re working on.

- But maybe the hammer is a bit too heavy, this starts to make it stand out. Now you can take notice of it, but still in a way related to the task of hammering. “Too heavy” is still not a property of hammers, but something that exists in this context, for you, at this time. A sledgehammer may be too heavy for building a birdhouse, but not for smashing rocks.

- With further reflection “Too heavy” can become “heavy” where you notice that it has weight, independent of your current task. This too is a further decontextualization of the hammer into a separate object.

- Finally, if you were a modern thinker, you might say that the hammer has mass, something even more decontextualized and independent.

And there’s nothing wrong with doing this! Indeed, you can learn a lot by removing the “world” from the things you encounter so you can study them scientifically. Our modern world is built on this ability.

But, at the same time, it’s important to recognize that this isn’t our typical starting point. If you start with the raw physical properties of the hammer, Heidegger argues, you couldn’t “build back” to the skills for dealing with it in the world we live in.

What I Like About This Idea

I’m not a philosopher. I don’t really know enough about this to know whether Heidegger’s account undermines Truth or Reality or whatever.

But, I do have an interest in how the mind works, and this seems to be a more compelling account than the traditional picture.

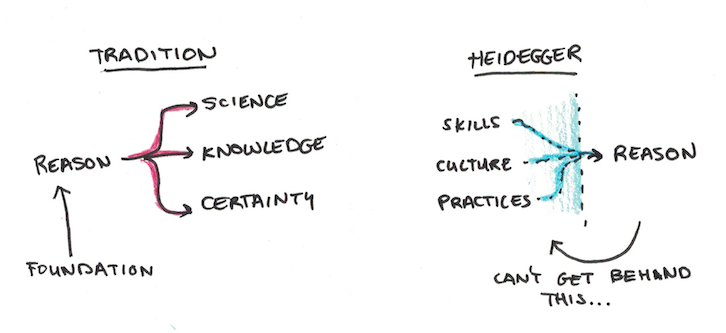

We know, for instance, that over evolutionary time, animals begin with motor reflexes for dealing with their bodies and the outside “world” (although not yet a cultural world at this point). Yet, tradition has largely assumed that reason arrived ex nihilo, as an add-on that is disconnected from those more basic abilities. It seems more plausible, to my decidedly non-expert eyes, that these kinds of skills might end up being the building blocks for abstract reasoning rather than the other way around.

Cognitive scientists have recently been coming to the appreciation that an unconscious runs most of the show for our brains. This unconscious is not a Freudian unconscious—thoughts that could exist in the mind but are simply repressed. Rather it’s an adaptive unconscious that allows our minds to work but does so in a way that could never be conscious. How are you controlling your eyes to read these words right now? How many saccades did you just make? You don’t know, yet those things make vision possible.

Heidegger’s notion of “world” is more cultural than biological, but I don’t see why that division is particularly important. Cultural evolutionary theorists like Joseph Henrich point out that many of our cultural practices are adaptive although we don’t know the reasons for them. Whether nature or culture, I agree with Heidegger that a lot of the “heavy lifting” that makes intelligence possible is being done in this background of activity that is largely invisible to us and which we cannot articulate the reasons for.

2. Rethinking Human Being

What does it mean to be human, deep down? Heidegger has a unique answer to this question. Except instead of using an existing word like “human”, “soul”, “consciousness” or “person” he decides to invent a new one: Dasein.

There’s a justification for this neologism. We have too much philosophical baggage attached to all the old words, Heidegger argues, so it’s impossible to see what he wants to show you if you stick to words infected by the old philosophy. If you want to start a new paradigm, you have to be willing to sound incomprehensible to those still attached to the old one.

Dasein is our way of being, which he also calls existence. (To Heidegger, hammers and quarks don’t exist, only things like us do. This doesn’t mean what you think it does. It’s just him redefining the word “existence” to apply to only this narrow sense. Yeah, I know…)

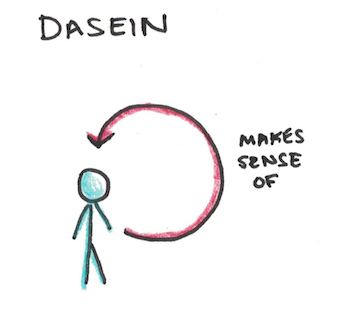

Our being, in essence, according to Heidegger, isn’t a rational animal, immortal soul, stream of consciousness or any of the other previous interpretations. Rather we are, at the base level, self-interpreting. We’re the being that makes sense of other beings, which importantly includes ourselves.

To be a human being, then, is to take some stance on what it means to exist. This is not a self-conscious identity. Indeed, the stance we take may be inarticulable, so it’s not as if saying to yourself, “I’m a father” or “I’m a video game addict” is what makes you human. Rather, it’s all the invisible practices that you’re so immersed in that they’re effectively invisible that allow you to make sense of yourself and be something unique.

This definition, that we’re essentially self-interpretation, reminds me of Douglas Hofstadter’s book, Godel, Escher, Bach. In GEB, Hofstadter argues that we are “strange loops.” Like the staircases in MC Escher drawings that continually go up, but somehow loop back on themselves, we are the things which, by our very constitution take a stance on the thing that takes stances.

Heidegger, however, takes this definition further. Combined with his definition of world, he redefines us once again as being-in-the-world. That “in” is supposed to mean more like “interaction” than “inside.” In this view, we’re not separate minds isolated from an external world, but inseparable from the world we deal with.

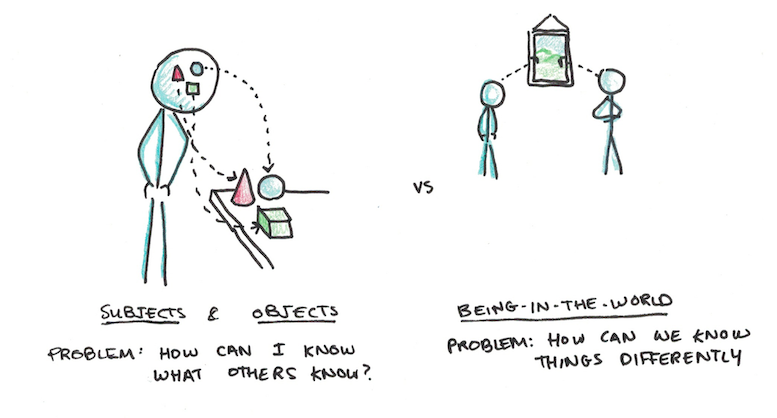

If you haven’t lost track of all of our redefinitions at this point (Dasein, existence, being-in-the-world), then at this point you find something rather original. The modern view is that we are subjects who look over objects, streams of consciousness, res cogitans or something similar. Being-in-the-world, in contrast says that while private experiences are possible they are not the default. To use Hubert Dreyfus’s explanation, our default way of being is to be “empty heads towards one single, self-evident world.”

Much of philosophy has worked itself into knots about how we can know things about the world, how we can ever really agree that we’re having the same inner experiences as other people, maybe we’re all living in the Matrix and this world isn’t real, etc..

Heidegger just decides to flip the problem around. If our basic state of nature is that we live in a shared world, then the problem of how we can agree on things is dissolved away. When you and I are looking at the same picture, we’re not each representing separate little mini-pictures inside our heads and struggling to compare them. We’re actually looking at the same picture.

Of course, in flipping the problem, this view of us as being-in-the-world creates new problems just as it dissolves old ones. If we inhabit shared worlds, how do we account for the fact that people have different knowledge of things, or that they can have false beliefs? If our basic existence is a shared, public world, what about dreams, the quintessentially private experience?

What I Like About This Idea

Heidegger’s concept of “world” seemed obviously true to me, once it had been spelled out. This concept of being-in-the-world doesn’t have the same obviousness, but it may be a fruitful paradigm, even if some of the problems aren’t worked out.

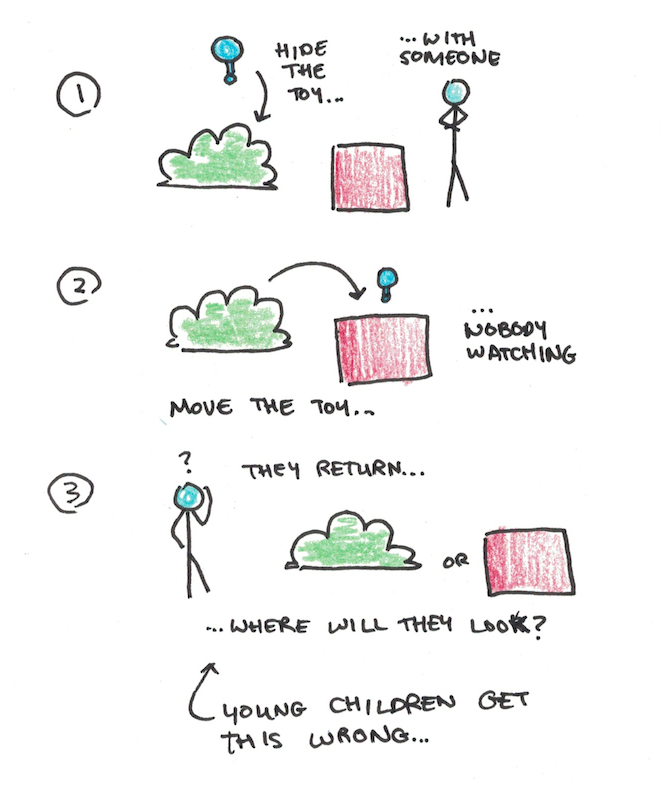

One thing I like about this idea is that it seems to correspond with our psychological development. Children start out as empty heads turned toward the world, but around the age of 3 or 4, they start to gain the ability to recognize that other people might have different beliefs than they do. This “theory of other minds” has been traditionally presented as a discovery, as if children were inherently solipsistic until they discover that other people actually exist.

But there’s another way to frame this story. What if being-in-the-world is simply more basic than having private experiences? Like the example with hammering being more basic than just staring at a hammer, it may feel like private experiences are more basic than public ones, but this might just be a bias from traditional accounts of philosophy.

Hubert Dreyfus gives some telling anecdotes to suggest our view of the primacy of private experience may be a modern invention. In Augustine’s Confessions, he recounts how people from far around would come to see Ambrose, the bishop of Milan. Why? Because he had this strange ability to read books without having his lips moving.

Similarly, Dreyfus recounts Homer’s Odyssey, where during a banquet the hero, Odysseus, is cited for his incredible ability to “weep inwardly” while having dry eyes. Apparently, in those days, the idea of having a private emotion was seen as a mark of extraordinary ability.

I suspect there is truth to this. Although we can all think of prominent examples when people lack knowledge we have, these might be “correctives” to a more basic sense that we all live in the same world. Especially when we take the concept of world at its broadest level, there are uncountably many “facts” about the world that we never even articulate, so deeply do we believe that they really are “there” in the world.

In this account, it’s not that children suddenly learn that everyone has a separate, isolated mind that contains totally different contents than one’s own, but that there are special edge cases where the normal assumption of a shared world breaks down and requires corrections.

Isn’t the idea of a shared world unphysical?

I think it’s important to point out that the idea of a shared world isn’t the same as saying a shared brain or consciousness. While it’s obvious to me that the brain is the source of all of the phenomena I’ve described so far, and thus must be processed by each individual human, that doesn’t mean seeing ourselves as possessing separate “copies” of the entire world inside our heads necessarily makes sense.

To use an analogy that isn’t metaphysical, think of torrenting files. In those cases, there is no central server or “global consciousness” holding everything altogether. But, at the same time, the entire file may not actually be present on any one person’s computer. All that’s necessary is a protocol for sharing and distributing it so that different people agree on the file contents.

Alternatively, there may be a sense that we have a shared world because the way our brain works is not by storing a copy of the world, but by using the actually existing shared environment to make decisions. You can catch a pop-fly by running to maintain a certain angle between you and the ball. This doesn’t require calculating the ball’s trajectory, but utilizing the fact that the ball has a trajectory in the environment to do the calculation for you. The difficulty we often have with running in dreams, may be a similar example, as kinesthetic feedback from the ground is normally needed to keep a smooth gait.

Thus it’s plausible that we live in a shared world, either agreed upon via an unconscious protocol, or through direct reference to the environment itself. The “theory of mind” that children gain, would then be the theory for spotting where this typical protocol for living in a shared world breaks down, and correcting the more basic understanding.

I’m not making any claims of having an algorithm worked out here, just to say that it doesn’t seem obviously unphysical to me that this might be our more basic makeup.

Dreams seem harder to reconcile with this, and private imagination in general. But I don’t think it’s hard to argue that dreams are impoverished relative to the actual world we live in. Maybe that’s the best argument against the idea that the world is purely subjective: that our dreams are pale visions of the world we experience when we’re awake.

3. The Hermeneutic Circle (and the Groundlessness of Philosophy)

Now we arrive at a difficult point. Much of philosophy has been preoccupied with how we can really know things for certain. How can we ground our knowledge on something that is beyond doubt? Medievals used to do this through appeals to God. Moderns have done this through appeals to Reason or Science.

However, if you follow Heidegger in believing that all these invisible skills and practices underpin our ability to do seemingly more basic things like just looking at stuff or thinking about things, then you get in a trap. The skills you have are far from a perfectly solid ground to rest your conclusions on. After all, different people, different cultures, different times have had different practices—so how could you possibly come up with the one final, indubitable Truth?

Heidegger argues that the only way forward is to do hermeneutics. Hermeneutics is the study of interpretation, usually applied to texts. The idea is that, if you want to understand Moby Dick, you have to start with some interpretation of what it’s about. (Say that this guy really hates that whale.) As you dig deeper, you may end up finding out that that initial understanding was flawed, or even completely contrary to where you started. (That the whale is actually man’s search for God.) But you’re always starting with something. There’s no way to go to the ground truth of What Moby Dick Really Is Aboutâ„¢, since you’re always in some partial stage of interpretation, given what meanings you’ve already started with.

This observation, that philosophy is fundamentally ungroundable, is seen as a major flaw for some. Doesn’t this imply full-blown cultural relativism? That truth is just a social convention, rather than anything deeper?

Again, I’m not good enough at philosophy to judge. It’s at least unclear to me whether Heidegger was an anti-realist in the way such beliefs would seem to demand. Heidegger makes a big issue out of the fact that beings do not depend on being, suggesting that the entities that exist in the world are, in a certain sense, independent of our intelligibility of them. This would imply that there really is a causal underpinning of the universe that doesn’t care what we think about it, and thus a proper object of scientific study.

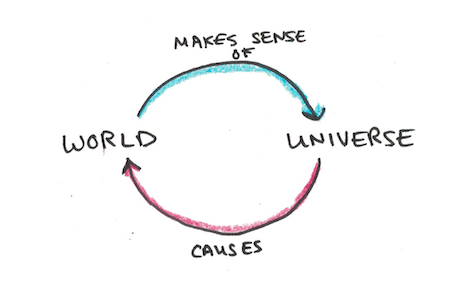

Heidegger’s hermeneutic circle starts and stops with phenomenology. But to me, this feels like too narrow a way to think about the world. While it is true that we have to start somewhere, even if that’s totally wrong, when understanding the universe, I don’t see why that circle can’t encompass physics, biology, psychology, economics and more.

If we expand this circle wide enough, I think we can start to see how more “basic” studies start to look more advanced. Physics, after all, is the study of the most basic things in the universe. But, at the same time, the physics department in a university is made of some of the most complex things in the universe: human brains doing physics. To understand what it means to “do physics” requires understanding psychology, neuroscience, biology… back down to physics again. A circle.

I tend to think people make too big a deal about this kind of ungroundedness. Yes, it does mean that we can never be certain we have found the right answer. But I don’t see that this implies the opposite worry—that everything is totally relative and arbitrary.

Certainly the causal properties of the universe influence the beliefs and practices we form. Thus I don’t see why we can’t simultaneously admit that science is based on a specific set of cultural practices (publishing papers, weighing evidence, deciding what makes a “good” experiment, etc.) but not also see that these practices fit together with the thing they study. A hammer may not be understood, in its most basic way, as just a blob of metal on a wooden shaft. But a hammer made of Jello couldn’t work at all. Science seems constrained by the universe, even if it does require human minds with cultures to implement.

How to Avoid Reading Being and Time (If You Wanted to Know More)

Some of the ideas that Heidegger makes a big deal out about, I either can’t make sense of or didn’t seem compelling to me. The book is called Being and Time, for instance, because apparently time is the key to understanding being. I didn’t get it. Don’t misconstrue my cherry-picking interesting ideas for a blanket endorsement of Heidegger. Your mileage may vary.

If you’re interested in learning more, I still don’t recommend reading the actual book unless you’re willing to grind through it for a couple of months. Instead, I recommend the following:

- Being-in-the-World. Documentary about Heidegger’s philosophy. It captures a lot of the ideas (including some later Heidegger stuff) which I didn’t include here.

- Being-in-the-World. This book is Hubert Dreyfus’s original exegesis (and also the reason for the title of the documentary). This goes into a lot more philosophical depth than the documentary, if you wanted to really know more, but still shields you from the worst of Heidegger’s writing.

- Being and Time – Division I. This is a full class, originally taught at Berkeley, by Dreyfus, about Heidegger. This was my main companion for understanding the book, although it doesn’t cover the later existentialist stuff in Division II. Dreyfus does have a class on that too, but since he also can’t seem to make sense of that part of the book, I didn’t find it helpful.

- Stanford’s Wiki on Heidegger. Probably the best short description of Heidegger’s thoughts, which also includes his later ideas about art, styles of being, technology and culture.

One takeaway from this project is that I should probably read more philosophy. Maybe if I do, I’ll end up taking back a lot of the things I agreed with so far. But thinking is always a work-in-progress, so I’m content to share what I find along the way.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.