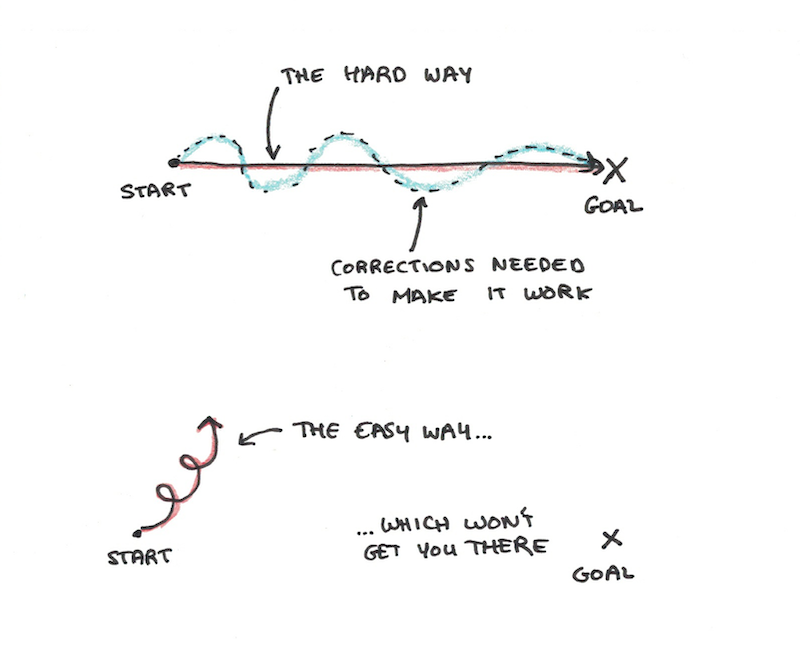

In my previous essay, I argued that much of success boils down to a simple maxim: do the real thing and stop doing fake alternatives.

Always start by asking yourself: “How would I do this, if doing it well were all that mattered?”

Now, you might object: You don’t have enough time. You have a job, kids and responsibilities. Doing it well sounds too daunting.

This is okay. The point of this thought experiment isn’t to deny that obstacles exist. Rather, it’s to start with the best plan and make accommodations as needed. What results is usually much closer to the ideal than if you simply start with something that feels easy enough.

How Would You Do It, If Doing It Well Were All That Mattered?

Let’s look at some examples:

You want to learn a language. The best plan is full immersion. You can’t do this completely though, so you make some exceptions for work, friends or family members. In the end, you only spend 60% of your conversation time speaking the new language.

In contrast, imagine you start by asking what’s something easy you can do? Now you end up downloading an app, listening to a podcast or telling yourself you’ll speak it “as much as you can.” The result? Maybe 1% of your conversation time is in the language. Maybe you never use it to communicate at all.

Say you want to start a business. The best plan is to build a prototype immediately of your intended product. You start interviewing prospective clients, getting preorders or contact information. But you can’t do this perfectly—you can’t quit your job yet and you can’t get financing.

The resulting path, however imperfect, is still a hell of a lot better than randomly reading business books or printing business cards or whatever convenient activity would have replaced it.

Maybe you want to get in shape. You figure the ideal path is to plan meals and stick to a precise workout schedule. You have to modify this to fit your life, but it gets you further than just buying a standing desk or telling yourself you really should try to exercise more often.

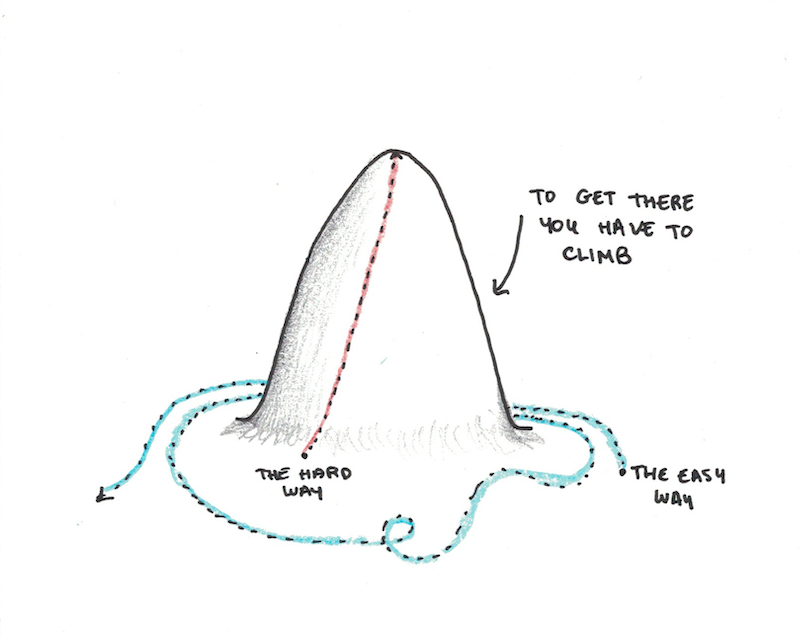

The Paradox of Difficulty

A pattern in my own life, and one you may have seen as well, is that the hardest things end up becoming the easiest, once you’ve fully committed to them.

Most pursuits have some unavoidable effort. You can either choose to commit that effort, or find ways to pretend it doesn’t exist.

If you choose to commit, you make the pursuit a priority. You put it first in your calendar. You expect frustration, setbacks and obstacles. You’ve made yourself stronger, instead of trying to avoid lifting the weight.

Paradoxically, it’s those who ignore the investment needed that experience the highest costs. It’s hard to hit a target when you’re aiming out of the corner of your eye. Difficulties arise precisely when you expect things to be easy.

How to Commit to the Hard Way

The way forward is simple. It just isn’t easy:

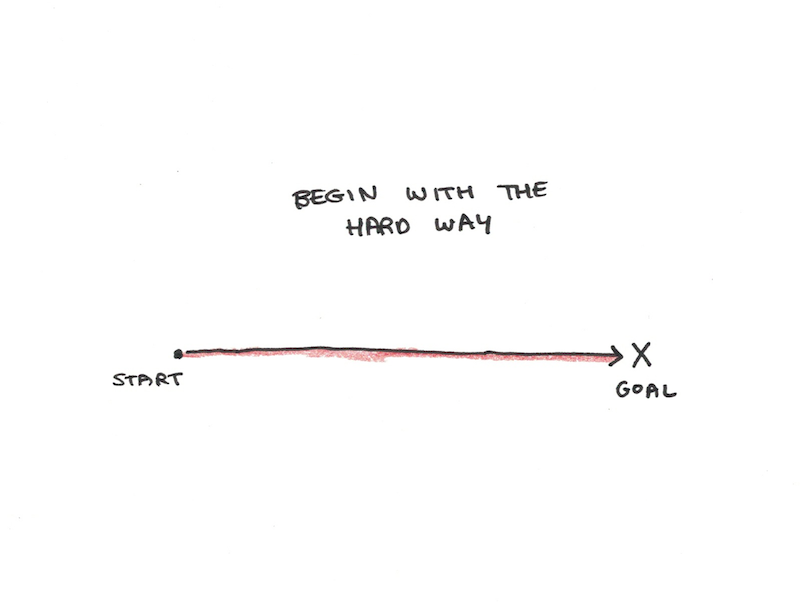

1. Begin with what would work best.

Start with what would work best. Hold the buts and whatabouts for later. Merely asking what the ideal strategy would be doesn’t yet commit you to it. But it forces you to recognize the effort inherent in the path ahead.

Focus on what you’d be doing, not how much. The “what” turns your attention to the real thing. “How much” matters too, but it should come after. While intensity can be scaled, the real thing doesn’t have easy substitutes.

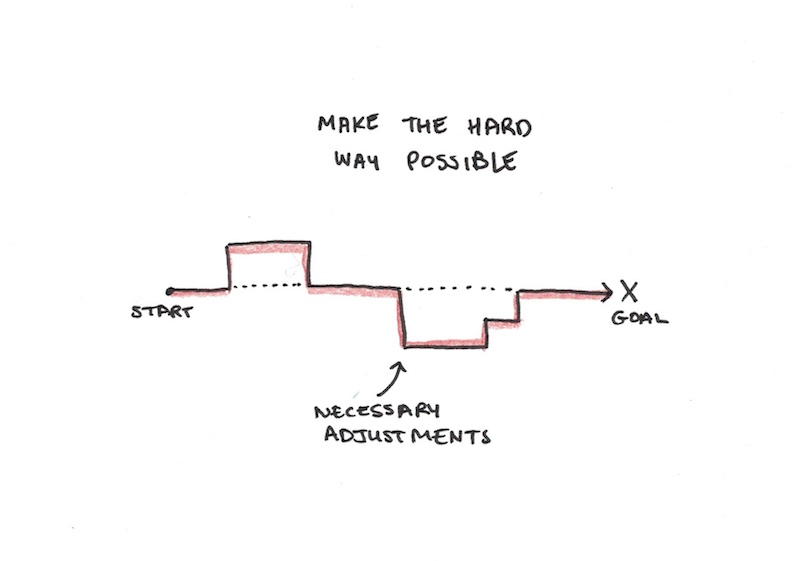

2. Make the best possible to attain.

Starting with what would work, you now ask how you could make it possible.

Maybe the real thing is inaccessible. You want to learn a language, but you’re stuck at home. You want to work in a real firm, but they won’t hire you. You want access to the training ground, but it’s off-limits.

Now is the time for substitutions. Approximating the real thing is tricky, but it’s far better than efforts that don’t even strive for verisimilitude.

You can’t travel, but you aim for immersion at home. You can’t work in the real office, but you train on the tools they use. The training ground is off-limits, so you build your own in your backyard.

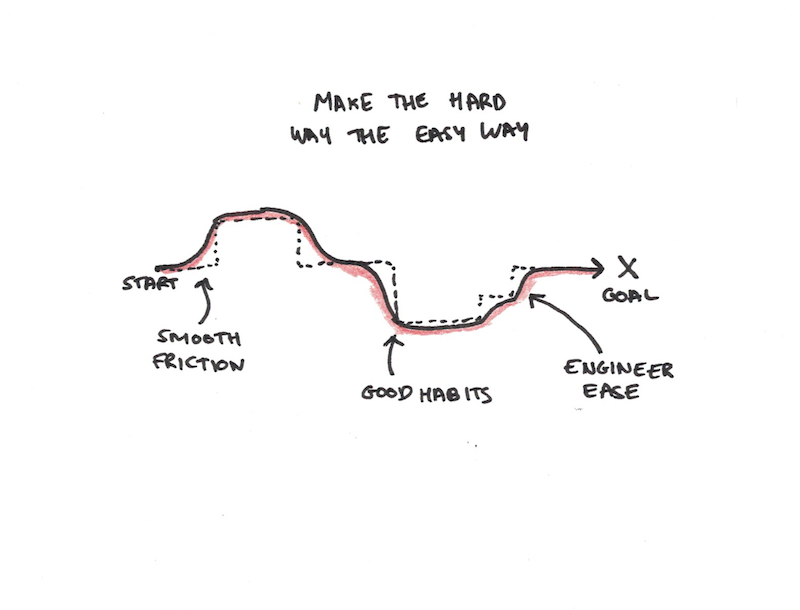

3. Turn the hard way into the easy way.

Now, and not a moment sooner, is the time for engineering ease into your efforts.

The timing is critical. Starting with what’s easy, you’ll be tempted to substitute something convenient for something that works. Once you know what needs to be done, however, do everything you can to make it easier to execute.

Smooth friction. Ask for help. Cultivate good habits, systems and routines. Throw every hack, trick or tactic you have at the problem to make the path a little less treacherous.

If You’re Not Willing to Do it Well, Why Be Willing to Do It at All?

The hard way forces a choice: are you willing to invest the effort required to do it right?

As with any real choice, sometimes the answer is no. The cost is too high, other obligations take precedence or you simply don’t care enough. No is always a valid answer. Better to say it now, than let it rot away your resolve over time.

But if your answer is yes, then you know the path. All that’s left is to walk it.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.